A history of modern multihulls

How unballasted multihulls have come to dominate the modern sailing scene.

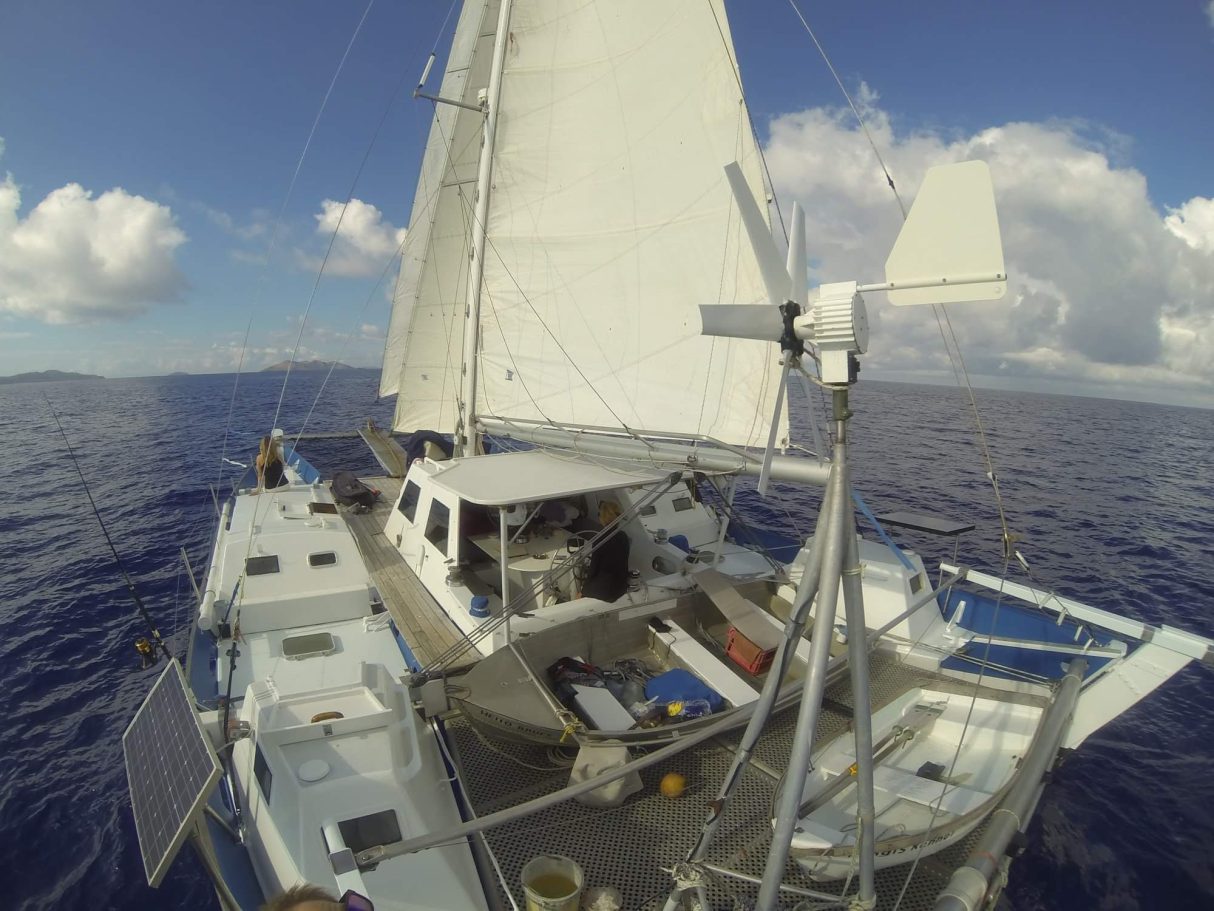

Today multihulls can be found in every port and every anchorage around the world. The multihull concept is used in passenger ferries and motorboats and the catamaran dominates charter fleets. The fastest ocean-going racers are the Ultim class trimarans, but it was not always like this. Yachtsmen it seems are inherently conservative and even though multihulls as a concept date back millions of years and are more traditional than the deep keeled mono hulls that were a 19th century invention for many year the yachting establishment of yacht clubs and racing associations considered multihulls as dangerous and unseaworthy. In the 1970's the establishment in the form of some journalists decided to bite back highlighting the capsizes and breakups that had accompanied the growth in numbers of often home built trimarans and catamarans throughout the 1960's and branding them "unsafe on any sea".

Multihulls started with canoes in the South Seas which were found by Western explorers as they "discovered" the Pacific Ocean. French, Spanish, Dutch and English sailors observed the natives of the islands of Polynesia coming out to greet them in small canoes usually with a single outrigger. These little canoes were transport for one or two people but then thy also saw larger canoes many of which were very large ocean-going vessels. It is possible to distinguish between single outrigger canoes, double canoes and double outrigger canoes. In terms of 20th century modern multihull development we talk in terms of Proas (which are basically a single outrigger vessel of the original Pacific configuration that flies the outrigger to windward; or Atlantic configuration that has the single outrigger to leeward and resembles a trimaran without the windward float); trimarans that are a canoes hull with outriggers on both sides; and catamarans that are the big voyaging double canoe configuration.

It is now well known that the populating of the Pacific Ocean and its Islands took place by sea starting it is believed with migrating voyages out from Taiwan and the Polynesian peoples settled in the Polynesian Triangle of New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter island about 3000 BCE. The Western approach to the anthropology of the peoples of the Pacific was based on a premise that the people of those Islands must have come from the American continent and populated the Islands by drifting on the currents. The reason is that Pacific trade winds blow from the northeast above the equator and from the south east below it. The Pacific trade winds drive surface waters toward the west to form the North and South Equatorial currents, the axes of which coincide with latitude 15° N and the Equator, respectively. Squeezed between the equatorial currents is a well-defined counter current, the axis of which is always north of the Equator, and which extends from the Philippines to the shores of Ecuador.

Western thinking assumed that the islands were populated from the east by drifting because they reasoned that the native vessels could not sail to windward against the trade winds from the southeast. Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl had a theory that the islands were populated by people from South America drifted to Polynesia and he built a Kon Tiki raft to prove the theory in 1957. His theory was that Easter Island and other Polynesian islands were originally inhabited by white bearded men from Peru. Suffice to say the theory was not accepted by scientists before the Kon Tiki voyage and is now largely disproved.

Unlike traditional Western sailing ships multihulls do not generally have ballast -other than their passengers and their stores. Their stability depends on the buoyancy in their hulls. Traditional ships from the Roman Galleys, Spanish Galleons, Tudor Ships and Napoleonic Ships of the Line through to the China Clippers and the big square-rigged ships of the 19th and early 20th century depended on the form of their hulls and the weight of their cargo (unless they were light when they had to take on board extra ballast) for their stability. many traditional yachts and the working boats were the same. All had in common that they can be laid over "on their beam ends" by a squall and swamped resulting in their sinking. This happened famously to the Mary Rose and still today traditional sailing ships are lost at sea for this reason. The concept of a self-righting keel yacht that can turn 360 degrees and be righted by the weight of its keel is a relatively modern one.

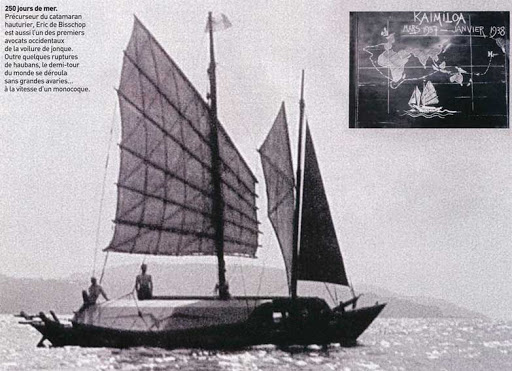

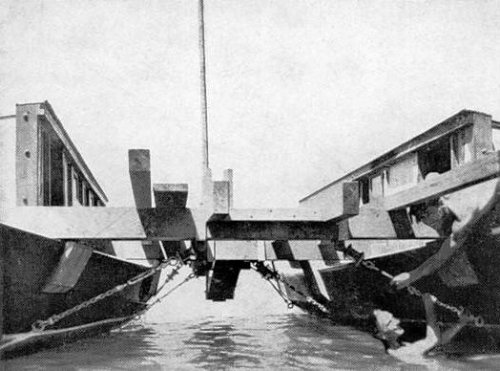

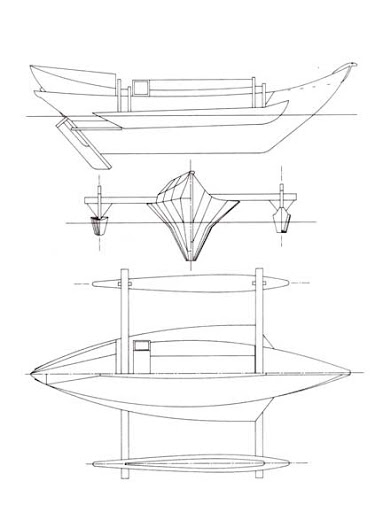

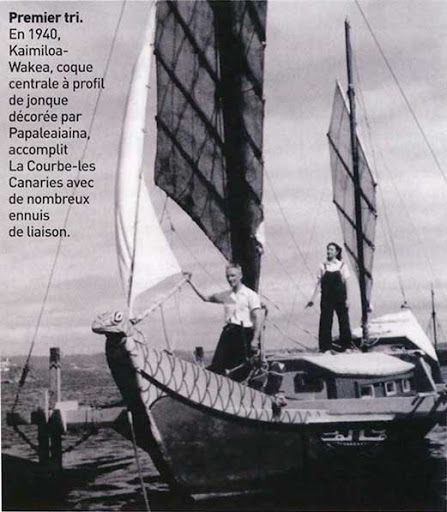

There had been several attempts to build modern craft that were multihulled and a much unsung pioneer was Frenchman Eric De Bisschop whose double canoe Kaimiloa voyage from Tahiti to France in 1939 was forgotten by most yachtsmen as was the fact that he then built a twin outrigger craft which was lost in a collision.

There were other voyages by French sailor’s voyages in a trimaran Ananda which crossed the Atlantic in 17 days in 1939 and then a steel catamaran Copula also sailed to the West Indies from Europe in the 1940's but World attention was caught by the resurgence in interest in Polynesia and the arrival of Woody Brown and his catamarans there after WW2. However, others were experimenting with multihulls and hydrofoils in Europe, America and the Pacific in the 1940's, 50's and 60's. The journals of the eccentric British Amateur Yacht Research Society have created a unique record of this. Bob Harris was designing catamarans from 1948, and Victor Tchetchet had started designing trimarans in the 1930's. Before leaving his native Ukraine to settle in America Victor built an 18-foot catamaran and entered it in a yacht race. He won but was disqualified. In New York after 1923 he continued to experiment and built a 20-foot trimaran, and he is believed to be the first man to use that name. He built other trimarans that he sailed successfully inshore in the 1940's and 50's particularly Egg Nog and Egg Nog II (1955).

In 1946 Woody Brown designed a 40-foot catamaran which became well known for its speed. In other parts of the USA others designed and built catamarans. The Lear Cat was a plywood catamaran 16 feet long and 7.5 feet wide with box section hulls. Her designer also produced an 18-foot version called Sabre Cat. Creger the designer then built a series of 32-foot cruising catamarans and a 35-footer that carried water ballast to add to stability. With narrow 12 foot beam this was not enough and one capsized on the Great Lakes. In 1950 there was a "One of a Kind Rally" in Miami and catamarans came from the USA and the UK. Bob Harris a young Naval Architect was inspired by Manu Kai and built his first catamaran in 1948. He designed several successful catamarans from 1948 to 1959 in his spare time while he worked for Sparkman and Stephens

In 1959 Bob Harris set up a Naval Architecture practice in New York in 1959 with Frank McLear. The firm of McLear and Harris specialised in multihulls from 1959 to 1967 when Bob Harris left and re-joined Sparkman and Stephens. He wrote two seminal books on cruising catamarans and trimarans. In 1970 he crewed for Phil Weld on his Kelsall trimaran Trumpeter in the round Britain Race finishing second.

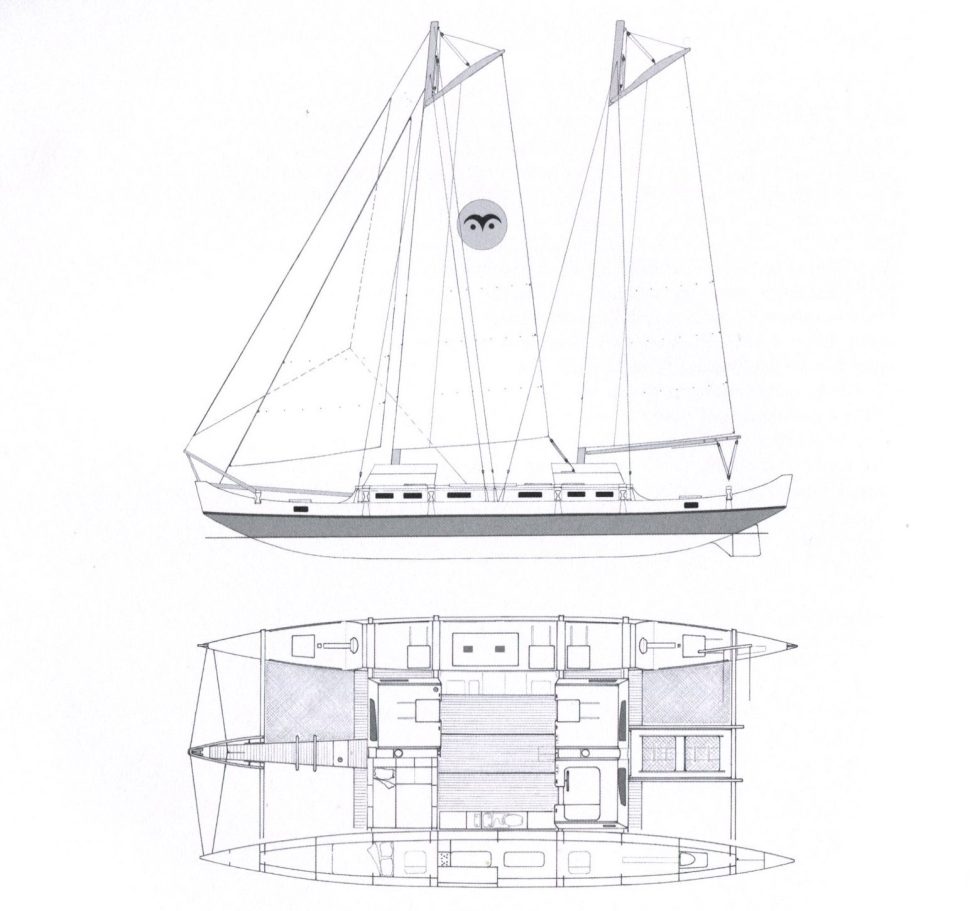

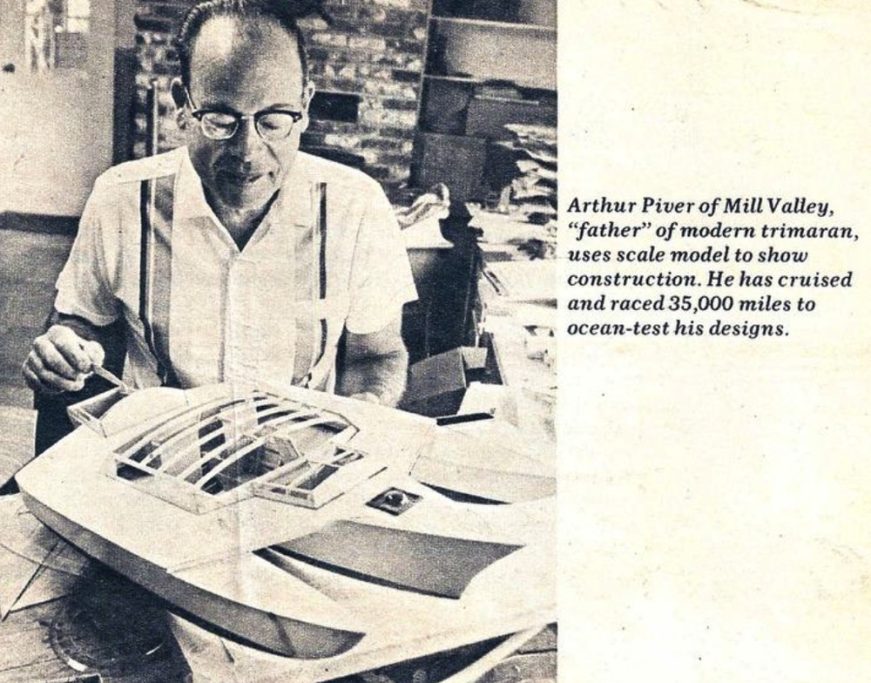

An almost "evangelical" advocate of trimarans was an American called Arthur Piver. He sailed his trimaran Nimble across the Atlantic in 1960 and in 1962 sailed to New Zealand from San Francisco. Piver had a massive impact and in the 60's and 70's hundreds of his trimarans were built by amateurs and professionals.

Woody Brown and Manu Kai - the beginning of the Hawaiian multihull movement.

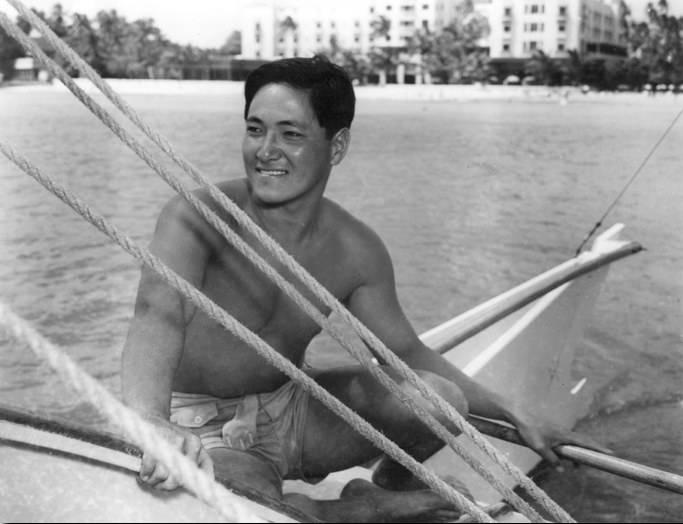

American Woodbridge Parker Brown (aka Woody Brown) was born in 1912 to a wealthy American family. Rejecting his family wall Street business, he became an original “surfer dude” but first started flying gliders with considerable success. In 1936 he stared surfing in California. In 1940 triggered by his wife’s death in childbirth Woody had a breakdown and walked out on his new-born son and his stepdaughter not seeing them again for many years. He headed for Tahiti but was held in Hawaii due to WWII. A conscientious objector and vegetarian he became one of Hawaii’s big wave surfers and designer of surf boards.

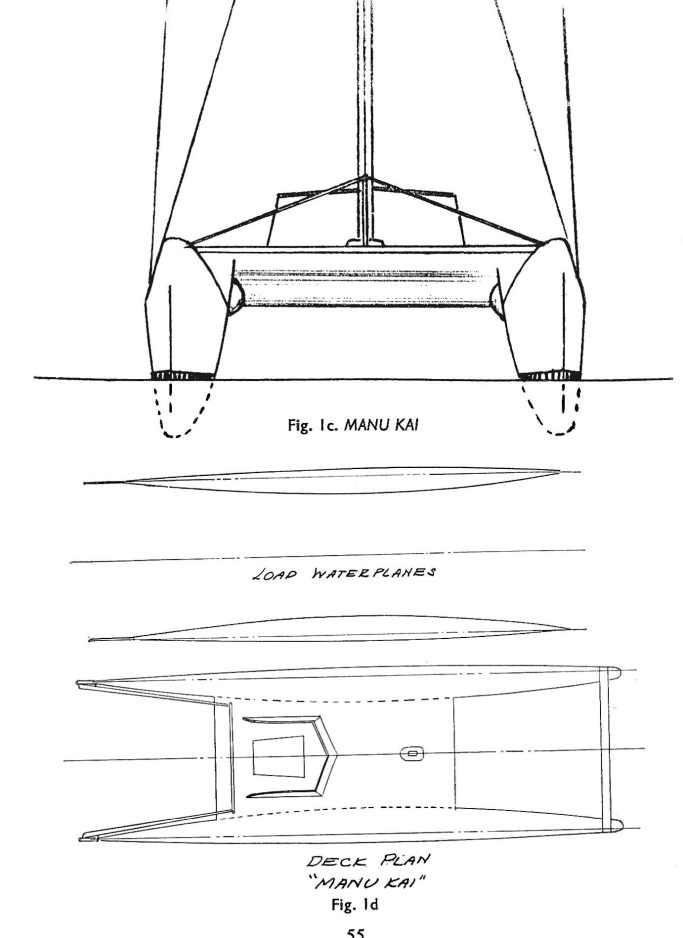

Fascinated by native outrigger canoes he designed a catamaran that was named Manu Kai (“Sea Bird”) and built by Alfred Kumalae and Rudy Choy. Built in wood on a beach at a cost of $4000 in 1947 she started the fashion for fast day sailing beach catamarans based at Waikiki Beach that continues today.

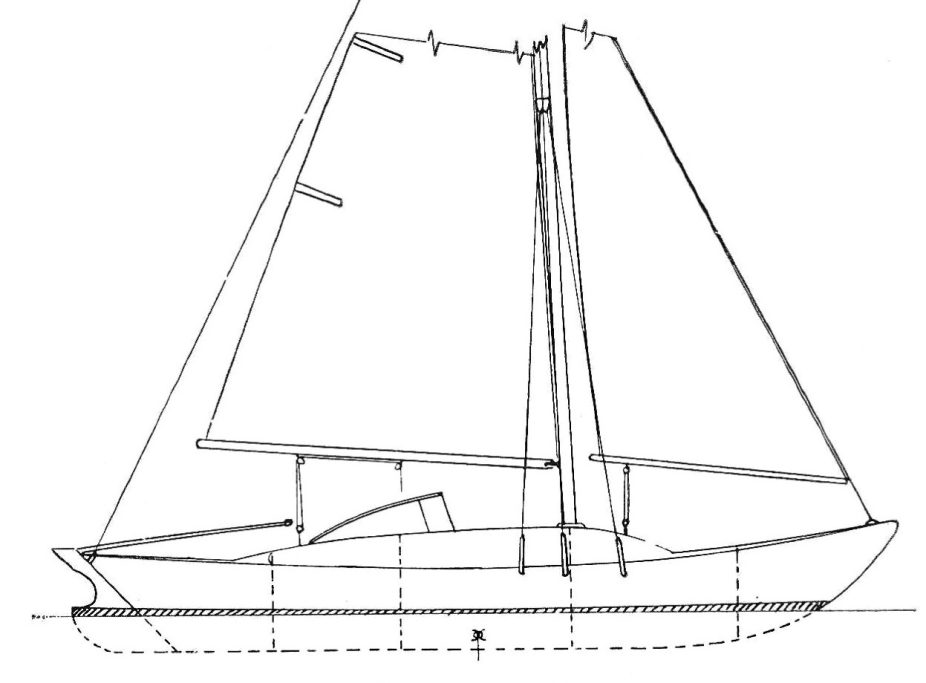

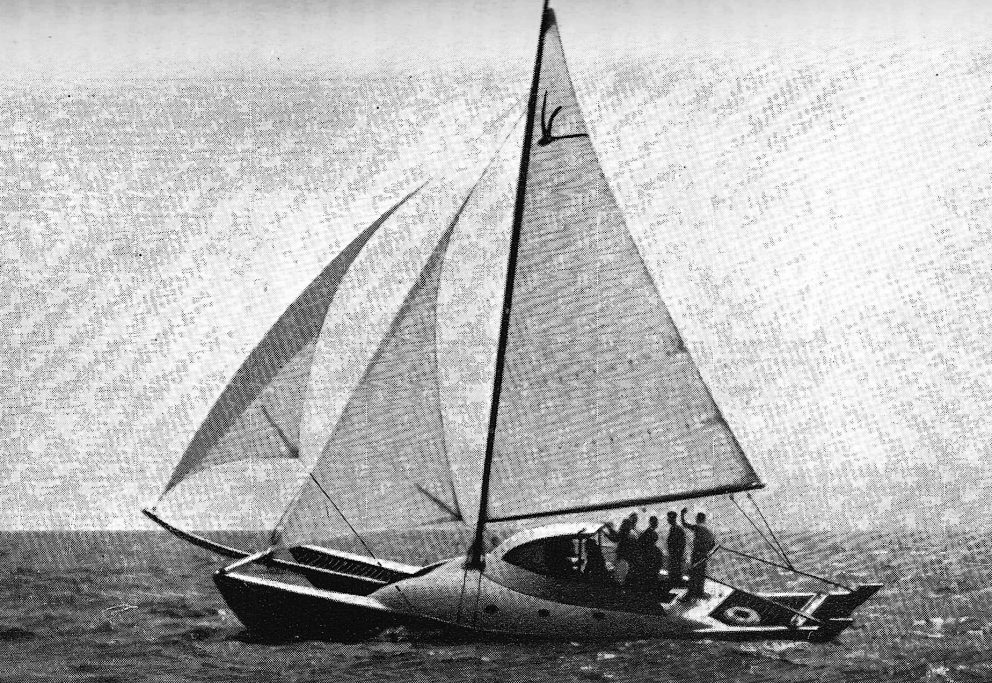

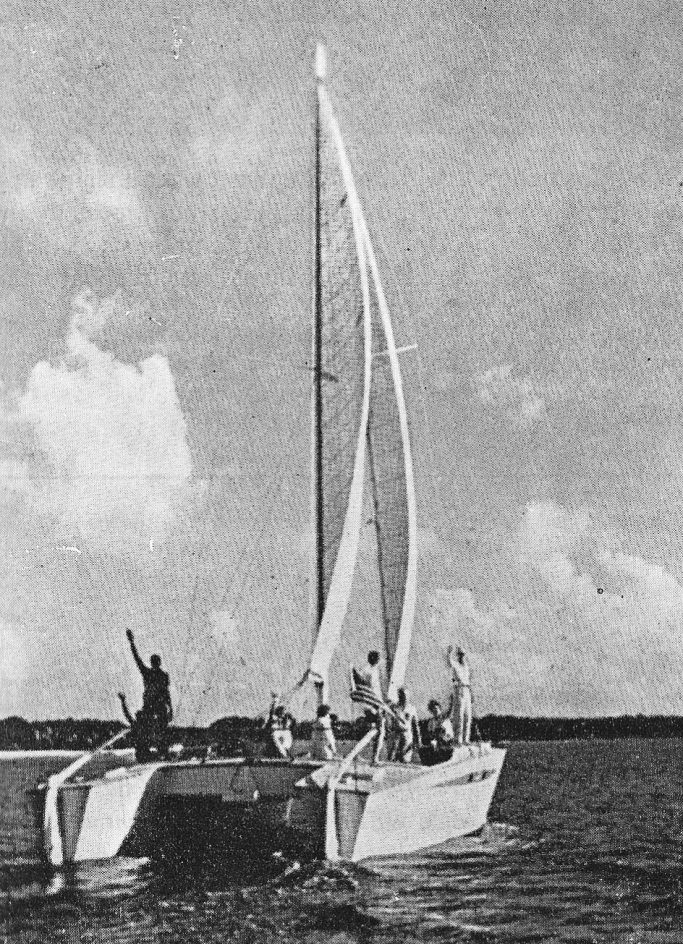

The photographs below show her launching and her on the beach and sailing. Manu Kai set a whole new style Brown was an experienced pilot and brought the aircraft technology he knew well into the project. Kumalae was an experienced boat builder and the construction of a monocoque was very well engineered. At 40 foot long her weight of only 1.5 tons was remarkable. She was 13 feet in beam and had hulls of a rounded V section with a flat outside, the theory being to gain lateral resistance by the shape of the hulls. Operating off Hawaii she was very fast indeed although even at the time it was noted by Bob Harris that she was slow in stays. As well as Brown and Kumalae, Rudy Choy gained a lot of sailing experience with Manu Kai and second version called Alii Kai This lead them to design and build another version called Waikiki Surf in 1955 40 feet long and 13 foot beam. Cutter rigged with a bowsprit she was given accommodation and equipped for longer ocean racing and cruising. Brown and Choy sailed her to Los Angeles but were refused entry to the Transpacific race from Los Angeles to Honolulu so the boat’s owner with another crew (Brown and Choy had to leave the boat) shadowed the race instead and finished fifth despite a stress crack in one of the hulls.

Choy was asked to design and build a larger ocean racer, and he came up with Aikane launched in April 1957. They took her in the Trans Pac race unofficially again as entry was refused and this time beating the fleet by 26 hours.

In Hawaii others followed Choy in the 50's building similar big Tourist beach cats like the 63 foot Ale Ale Kai III.

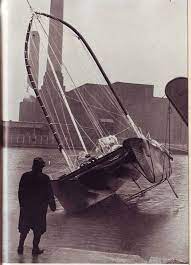

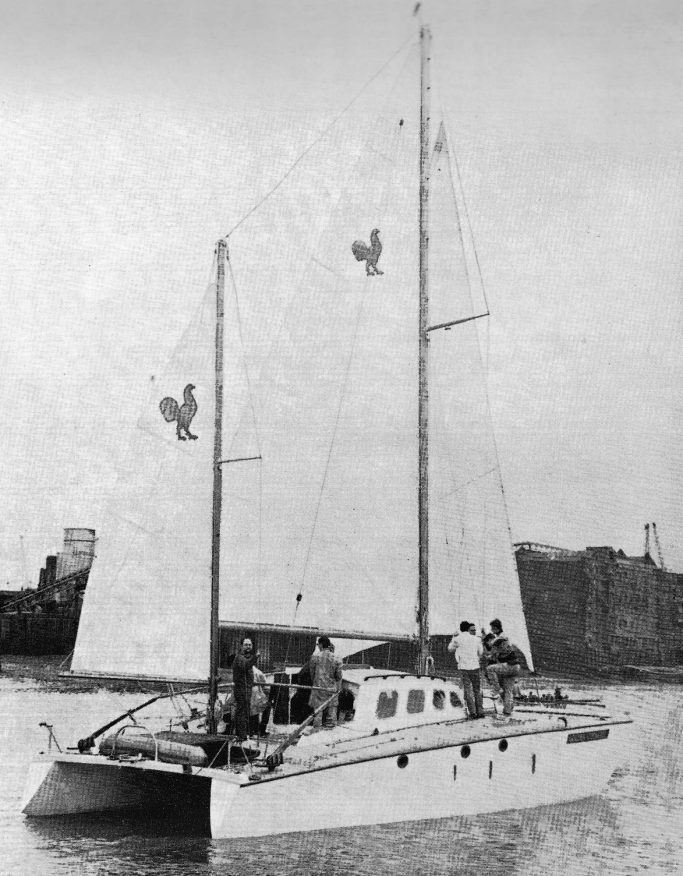

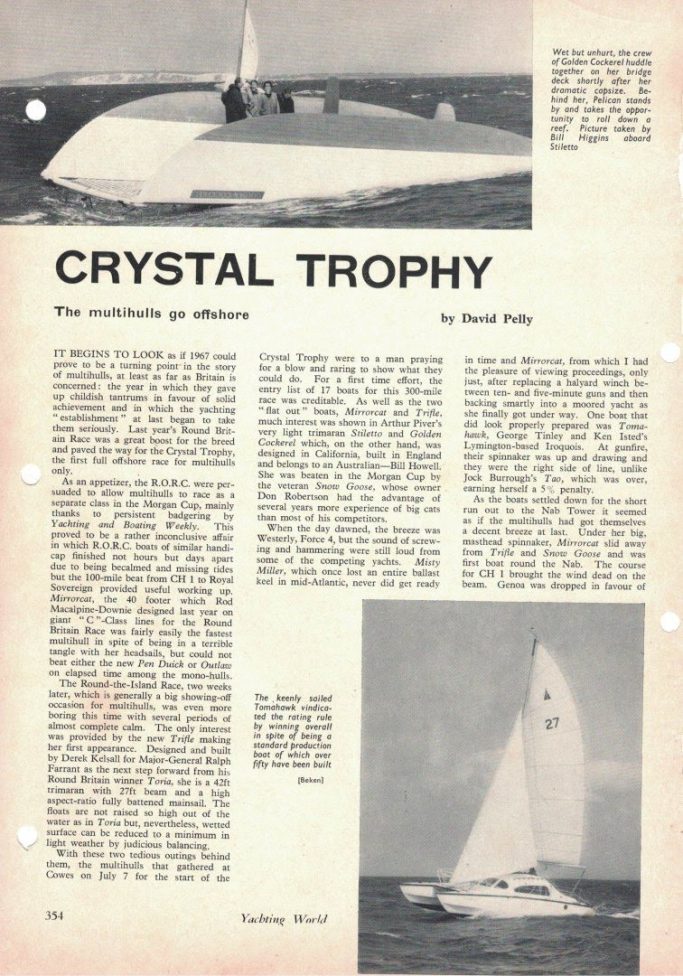

Rudy Choy, Alfred Kumalae and Warren Seaman formed CSK and became a hugely successful design team between 1957 and his son Barry Choy carried on Choy Design in Honolulu. In the 50's and 60's CSK were designing yachts for millionaire businessmen and movie stars that took up ocean racing in their spectacular catamarans which established many records. The 43-foot World Cat circumnavigated 1966 to 68. The Golden Cockerel to a similar design was sponsored by Watney Mann Brewery for Australian Dental Surgeon Bill Howell to enter the 1968 OSTAR. Entering the 1967 Crystal trophy race against Kelsall's Trifle and many others the catamaran spectacularly capsized. The wind was about force 6 and they were changing down headsails at the time. The weather hull was flying out of the water, and she was desperately over canvassed. The capsize was caused largely by crew inexperience causing poor seamanship because they did not know the yacht could capsize and failed to realise that flying a hull was the point of no return.

Today racing multihulls are designed to fly the weather hull like giant beach cats and racing trimarans are now given massive outriggers with their own rudders so they can fly two out of three hulls. The Ultim class and similar are designed to fly all three hulls as they race on hydrofoils.

In 1967 Great Britain the Golden Cockerel capsize sparked outcry from traditionalists and multihull sailors alike. James Wharram pointed out in a letter to Yachting Monthly, that his designs never flew a hull and were safe from capsize due to his design principles. But conservative journalists and pundits all voiced their condemnation of multihulls which was underlined by Piver's disappearance the following year.

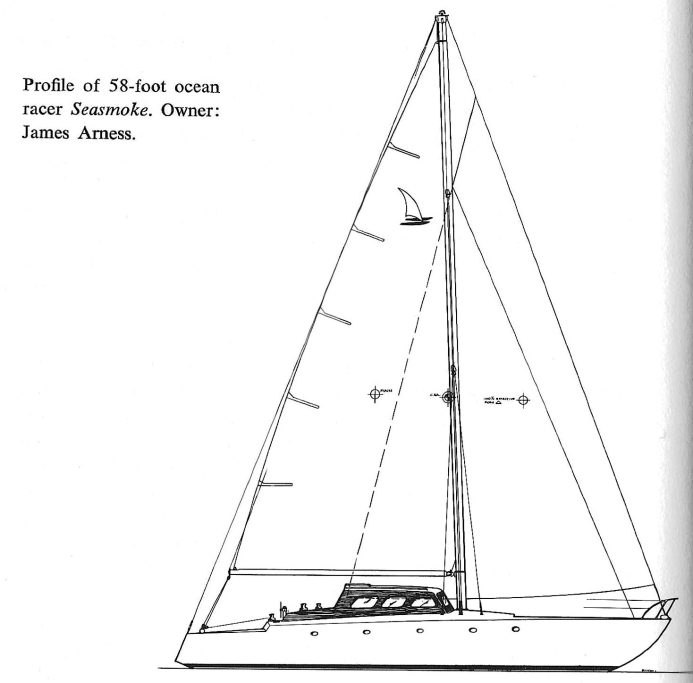

Howell recovered his boat and came fifth in the 1968 OSTAR. He enthused about how he had ridden out a hurricane in safety and went on to sail the yacht in several OSTAR's and Round Britain Races renamed Tahiti Bill. In the Pacific CSK catamarans raced and cruised. Records were broken. There were also capsizes which Rudy Choy explained as being mainly caused by inexperienced crews or pushing the vessels too hard. The 58-foot Seasmoke was one of Choy's greatest designs and owned by Jim Arness a Cowboy film star she won numerous races. There were production boats made in grp to a 25-foot design Polynesian Concept. Rudy Choy is another man that is revered as the inventor of modern catamarans, and it is certainly true that most catamarans today are closer to his monocoque hulls with bridge deck accommodation but there were many others following that path both in America and Europe. Never shy about his achievements Choy like Piver was a great self-publicist. His book 'Catamarans Offshore' was a great tale of his development of a very distinctive set of designs. His approach to multihull seamanship and the need to learn it was also ahead of his time because now capsizes are accepted as a regular occurrence in racing when boats are pushed too hard and mistakes made but that does not prevent most cruising catamarans and trimarans being built and sailed safely. In the 70's these occurrences which were largely the result of the need to develop and improve designs and seamanship.

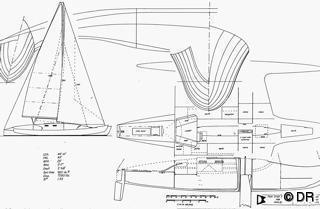

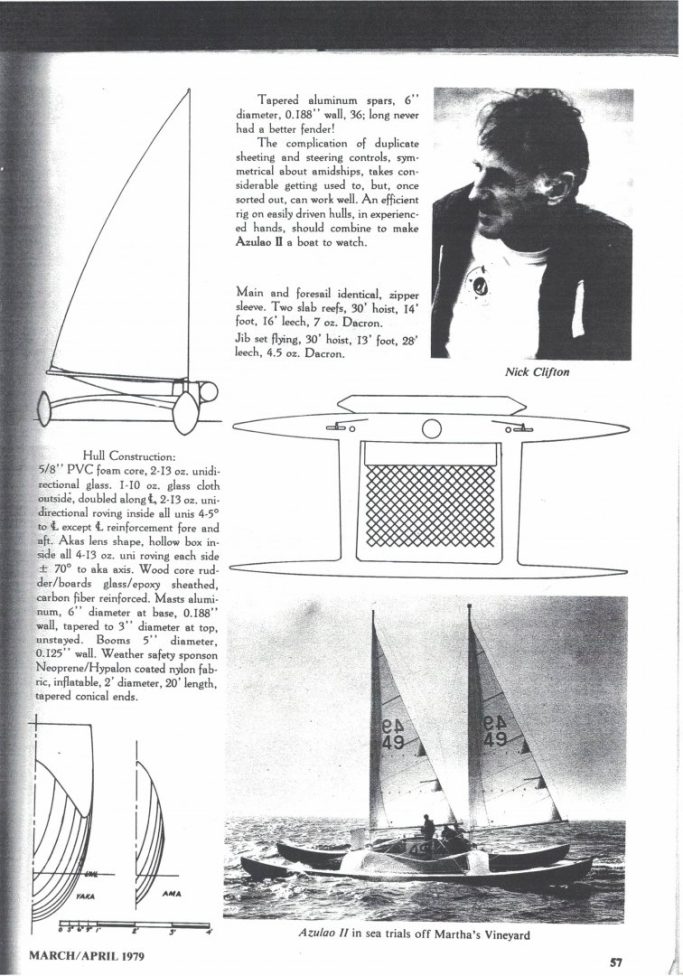

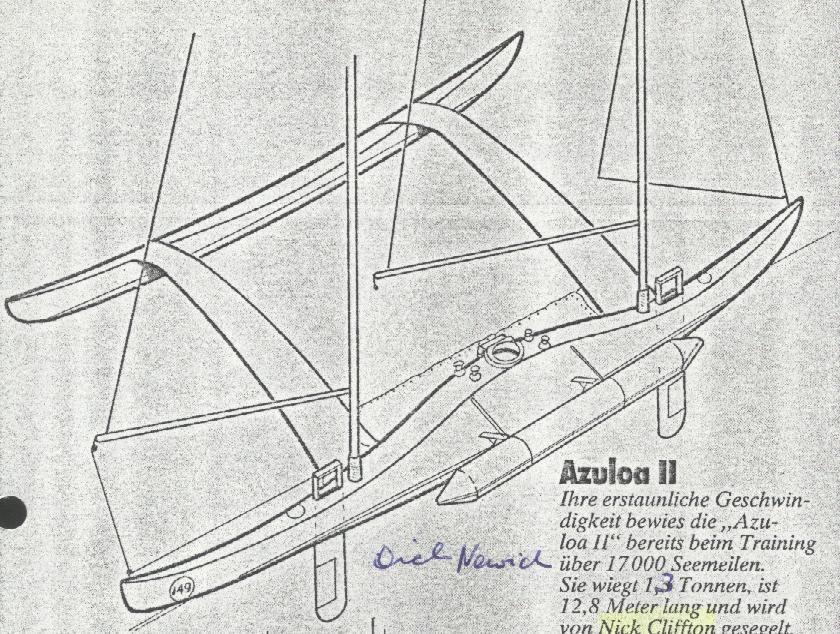

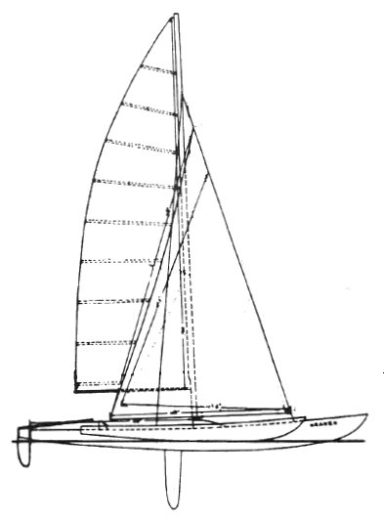

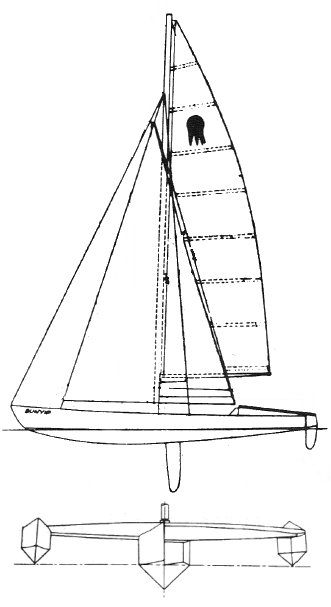

The development of multihulls in America and in the Pacific bloomed in the 60's and 70's as many designers worked on these craft. Maclear and Harris were designing very professional looking craft with a strong hint of Sparkman and Stephens about their style! Given Bob Harris' early development of smaller catamarans in the 1940's and 50's he and McLear remain rather unsung heroes too. In the Caribbean Richard C Newick was experimenting and designed a 40-foot day charter catamaran called Ay Ay that he set out to use in his day charter business. In Europe the multihull scene was less prominent until 1966 when Kelsall's Toria signalled the arrival of the racing trimaran to the establishment yachting scene.

There were big and small catamarans being designed and built in America throughout the 1940's,50's and 60's that were often very experimental and often unsuccessful in terms of their sailing abilities and construction. This can be traced back to Nat Herreshoff and his design Amaryllis a 24-footer launched in 1876 she beat 33 yachts in the New York Yacht Club Centennial Regatta. In 1877 Anson Stokes in New York launched a 60-foot schooner catamaran. Racing was closed off to catamarans as they were banned by the Yacht clubs, and they fell out of favour but still many were built experimentally and the concept used commercial applications. But it is true that after WWII the mood for developing multihulls was again awoken.

Eric De Bisschop

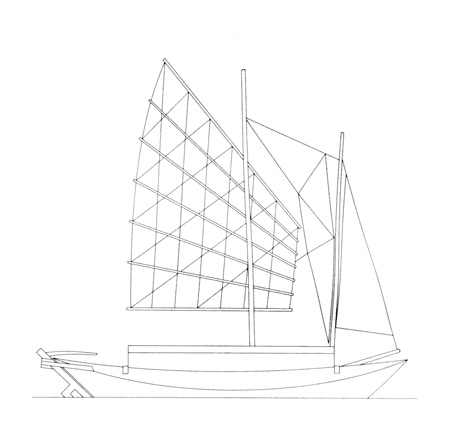

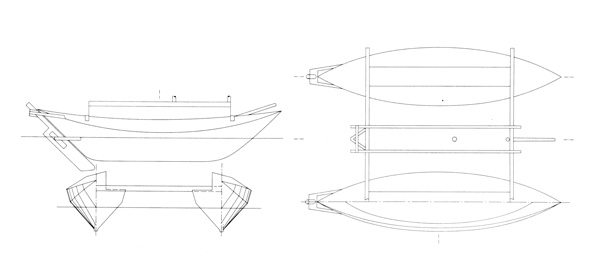

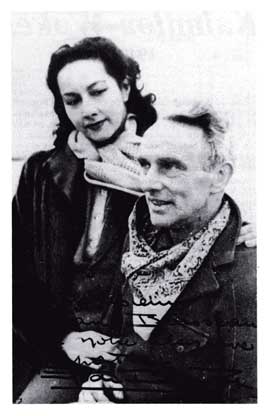

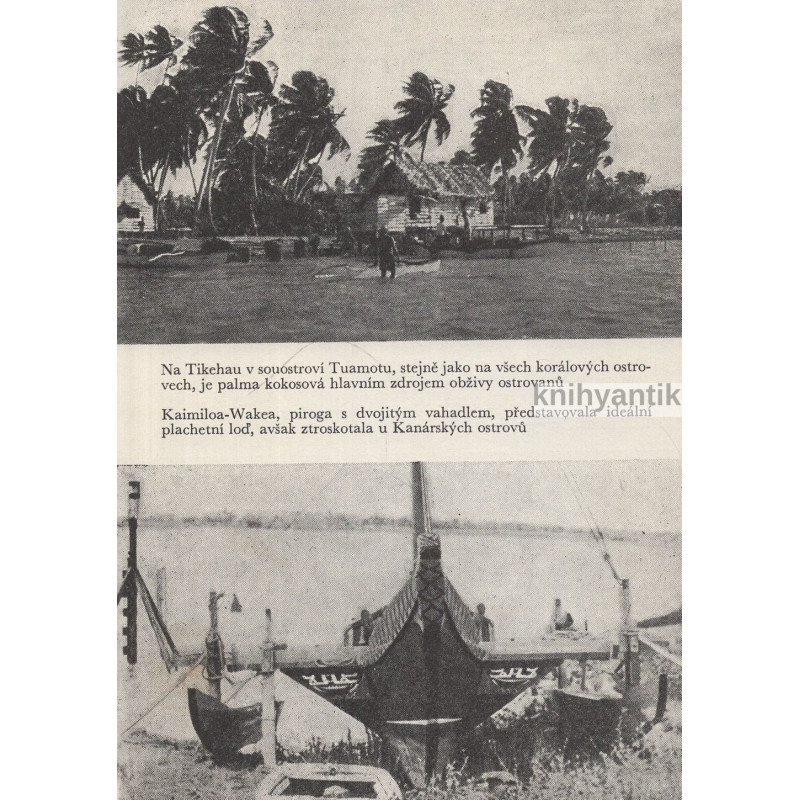

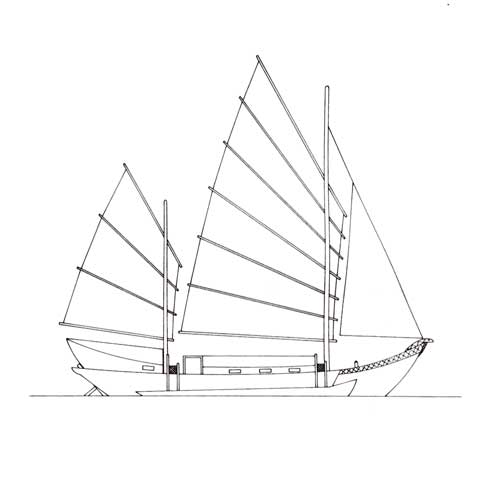

Born in 1891,Eric De Bisschop was a Frenchman and after serving as a flyer WW1 travelled to China in 1927 and built a Chinese junk that he and a companion sailed around the pacific. After losing her in a typhoon they build another junk and di scientific research in the Marshall islands. Wrecked in a storm they went to Honululu and in 1936 built Kaimiloa sailing her to Cape Town and on to France arriving at Cannes in 1938. He and hi wife built a trimaran called Kaimiloa-Wakea and sailed in 1940 for the Pacific. The voyage ended prematurely in Las Palmas when the boat was wrecked in a collision. Appointed by the French Government as Consular Agent for Honolulu they travelled back to his beloved South Pacific. Denounced for political reasons he lost his diplomatic status and was after the war disgraced for his relationship with Petain. In 1956 eric set off to disprove Heyerdahl by sailing a raft from Tahiti to Chili. A second raft was built to sail back and was wrecked in the Cook Islands and Eric sadly died on August 30 1958. Sadly his achievements with his multihulls and the amazing voyage to France which should have proved to all that a catamaran was a seaworthy ocean going concept are only recognised today.

The Prout Brothers

In 1947 Roland and Francis Prout in Canvey Island, Essex, UK were Olympic competing canoeists, and they joined two of their canoes together creating a catamaran. They continued the project with a second in 1949 but in 1954 they designed Shearwater 1 an 18-foot day sailor. It was very successful, so they developed it into Shearwater II in 1959. After testing this prototype, they shortened the hulls to 16.6 feet and started selling kits in wood in 1963. By 1964 a grp version was launched too. Others joined the process such as the Cunningham Brothers with their Yvonne Cat in Australia, Bob Harris with Ocelot in 1957 in America and Bill O'Brien developed Jump ahead in 1955.

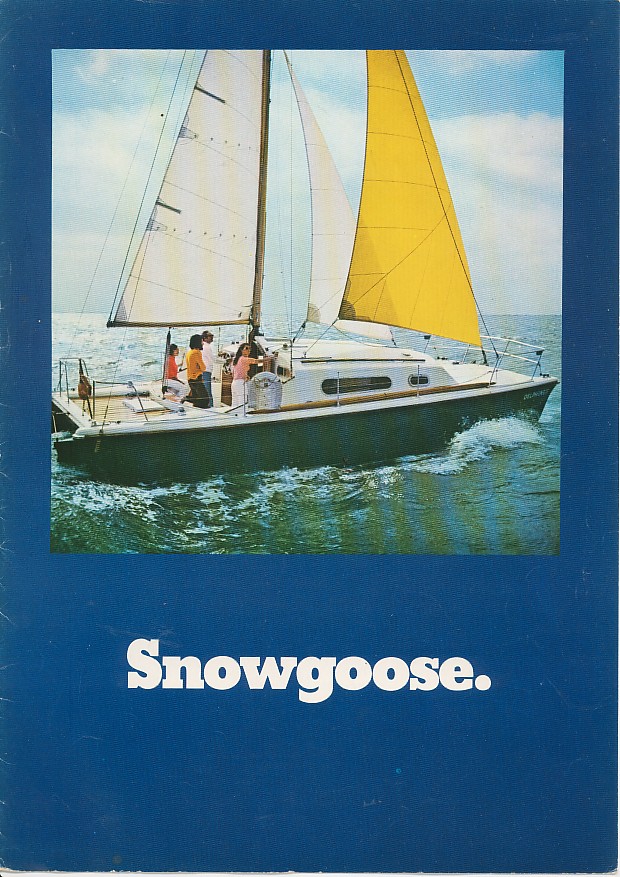

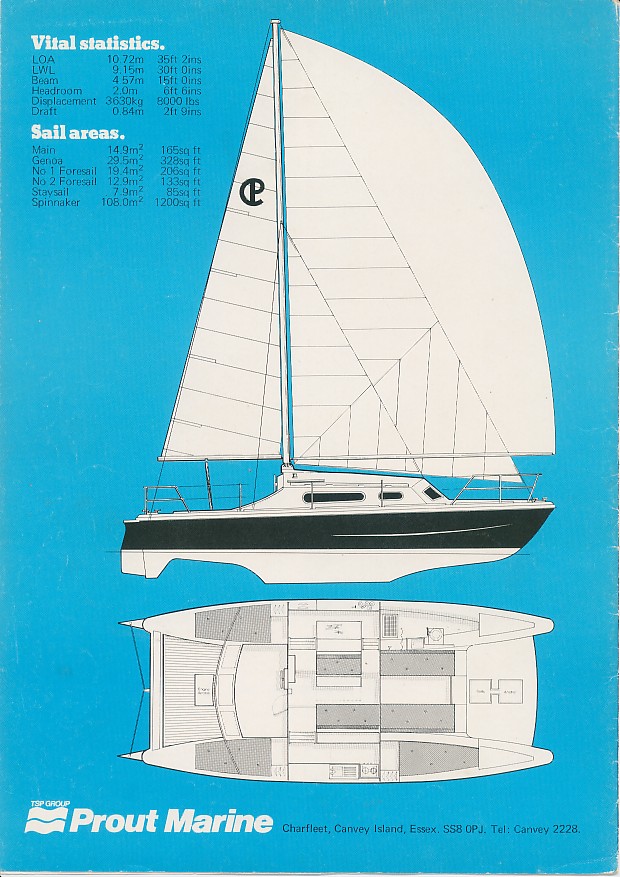

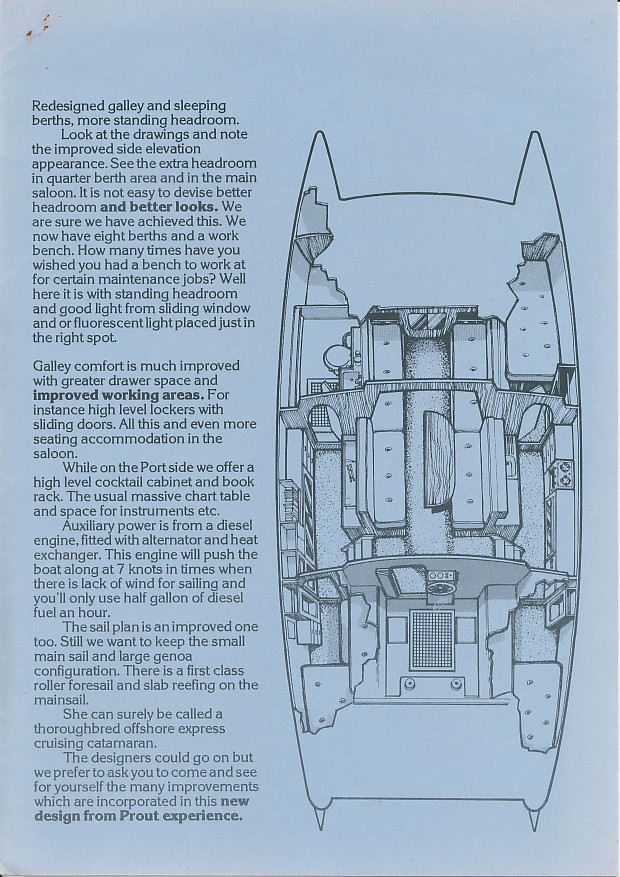

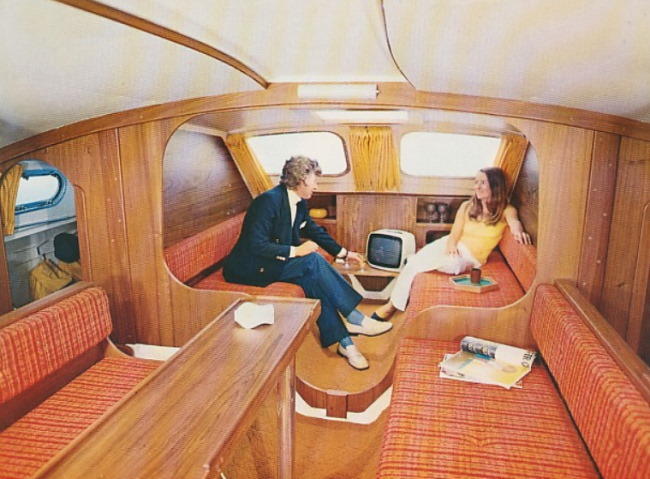

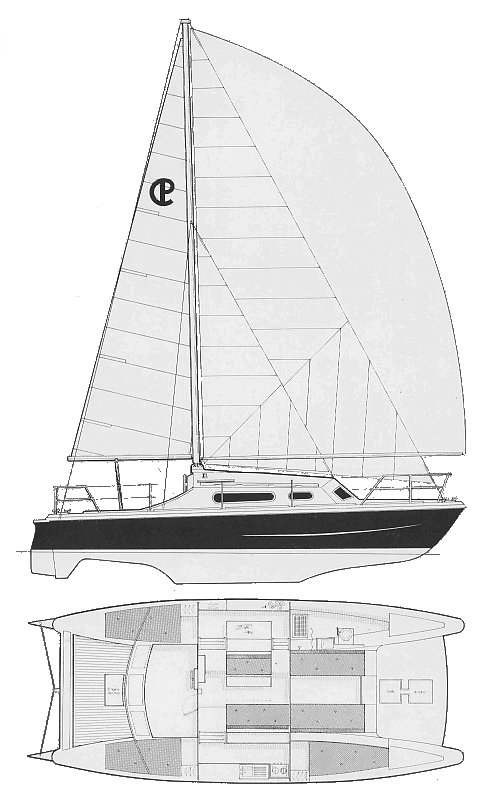

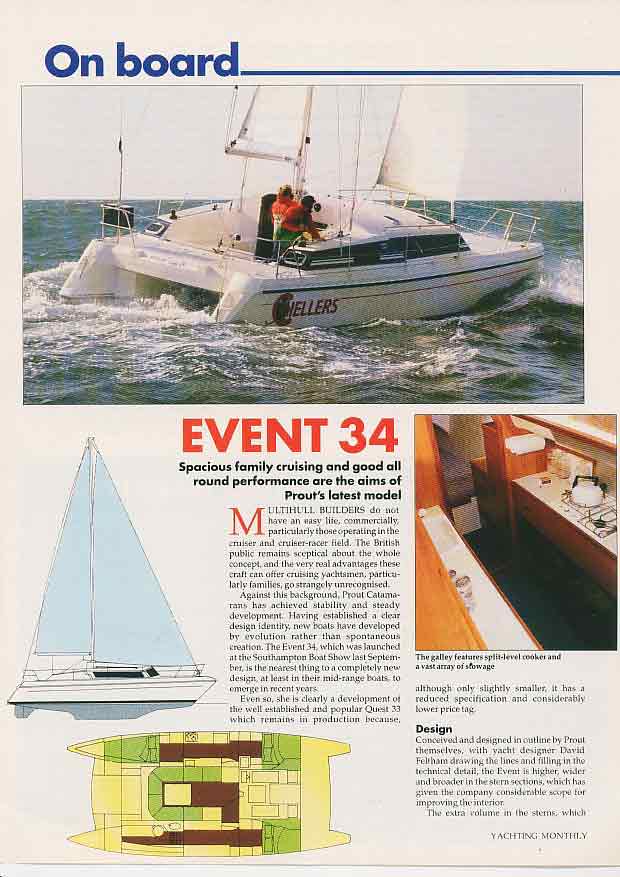

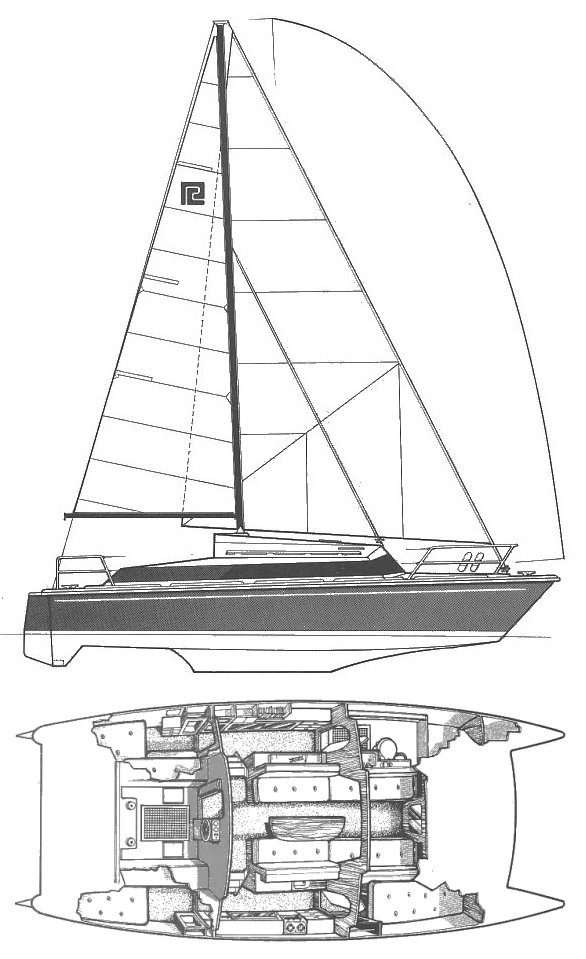

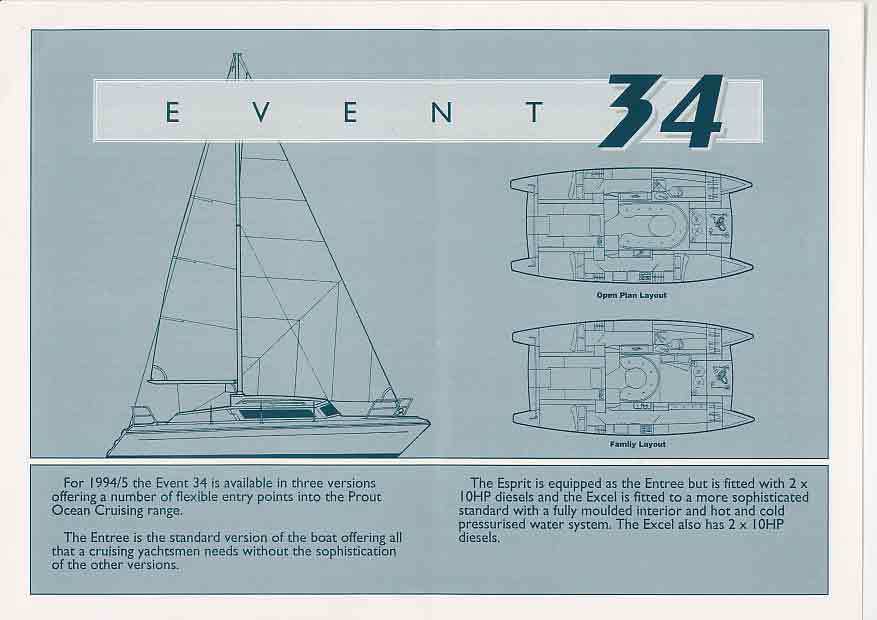

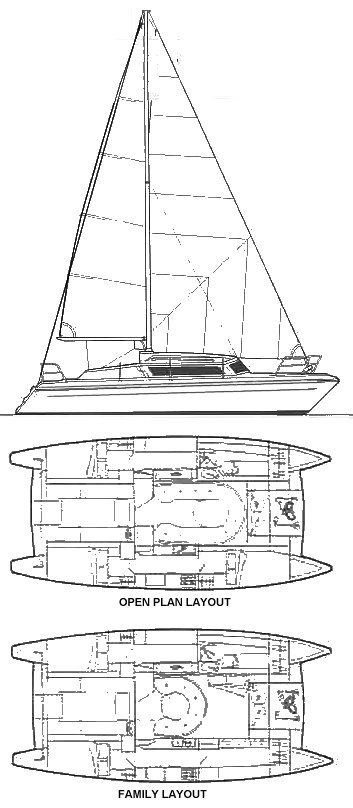

Cruising Catamarans were appearing as well as the performance day boats. Roland Prout corresponded with Woody Brown and Hugo Myers before designing his first in 1959 called Flamingo for Don Robertson. Don had experimented with a day sailor and l found Flamingo a successful cruising catamaran. In 1956 Prout’s built him another 36 footer called Snowgoose. Robertson went on to successfully sail Snowgoose an improved Prout catamaran in the Crystal Trophy, Round the island and Round Britain Races winning the latter in 1970 ahead of Weld's 40 foot Kelsall tri-Trumpeter. The Prouts produced a 19-foot cruising catamaran based on the Shearwater hulls and then developed a range of small cruising catamarans built in moulded grp, the Ranger 27 and the Ranger 31. Along the way they built a 40-foot catamaran Rheu Moana based on their hulls to the waterline with the remaining hulls and bridge deck designed by Colin Mudie for Dr David Lewis who took her on disastrous voyage to Iceland when the strange wishbone mast designed by Mudie broke. Rerigged with a standard Bermudan cutter rig Lewis took her on the 1964 OSTAR then sailed around the World with his wife and children and a very attractive young lady navigator (almost in the Wharram tradition!) and rumour was that he had one woman in one hull and one in the other. Certainly, his marriage did not survive the trip. But he had made the first circumnavigation by multihull. The yacht was much the better for the removal of the ballasted drop keels designed by Mude. Lewis went on to research and write the first academic study of Polynesian navigation. Sadly, before going to the South Seas Lewis had sold the catamaran - to fund his divorce perhaps? Rhu Moana passed through other owners until 1979 when she was restored in Cornwall before being wrecked in a storm in 1982. In 1966 Prouts designed and built what was claimed to be the biggest catamaran in the World a 77-foot motor Sailer called Tslamaran. However, after many cruisers that had sailed extensively they put an all grp 34-foot catamaran called Snowgoose into production in 1971. The hulls were outsourced to Thames Marine also at Canvey Island. This was a very unusual design with a large nacelle running the length of the full length bridgedeck keeping the boat very low in freeboard and height. The mast was stepped aft with a so called “Mins'sl" and large genoa jib. A whole series developed firstly the 35-foot version then the extended Prout 37 followed by a Snowgoose Elite 37 with extended hulls and greater accommodation. There were 26- and 31-foot versions of the Prout Catamaran. In the 60's they developed a Prout Ranger 45 which had "Whaleback" hulls and spawned many different versions from the Ocean Ranger to the ultimate 50-foot Quasar. After the retirement of Roland and Francis Robert underwood was the MD and the business which had won awards for export and was reputed around the World fell on hard times. Notwithstanding Robert Underwood's brilliant sales skills and the updating of the designs with the Event 34, a superb 45 (and a 46) foot design and continued the style of the larger boat in a more affordable guise of the Prout 38, the company got into financial trouble. In 2000 it was sold to a Canadian boatbuilder Quest. In 2001 the company went into receivership and a subsidiary of Quest bought the ongoing business. In 2002 the business went ito liquidation shutting the door for good. Most of the moulds apparently went out to South Africa where some more boats were built. The Prout 38 lived on as part of Underwood's new company Broardblue. A company in Hong Kong sold Prout 45's under the Prout International brand via yet another subsidiary of Quest. They sold boats built in Thailand and later in China but had ceased trading by 2013. A sad end to a great British brand that sold thousands of boats that can still be found everywhere. The number of ocean voyages and circumnavigations by Prout catamarans is almost too many to count. Today they seem rather dated and the World has not adopted the low bridgedeck nacelle (also favoured by Pat Patterson) or the Prout rig as catamarans now generally feature high freeboard, and big wide hulls lightly built in higher tech construction with palatial accommodation and big high roach mainsails but there is no denying the achievements of the Prout Brothers and the boats they built.

CSK and Hawaiian Catamarans

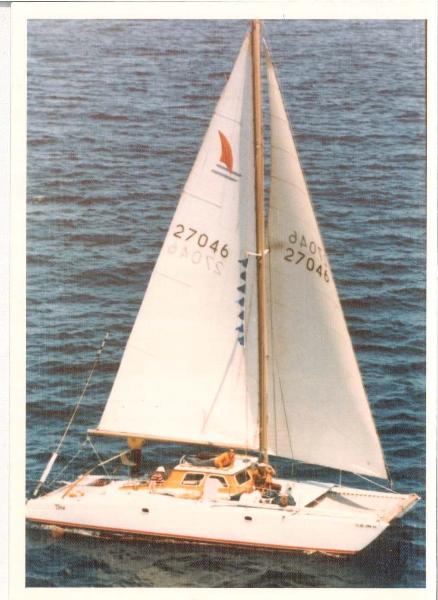

From 1947 Rudy Choy and Woody Brown started building catamarans that developed into the CSK design business which created a very iconic modern breed of seaworthy catamarans.

James Wharram

British Catamaran Pioneer 1928 to 2021

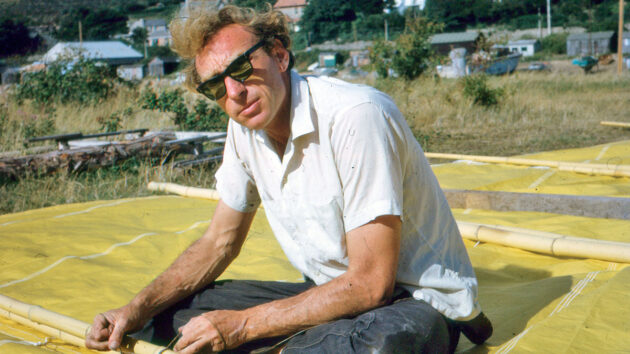

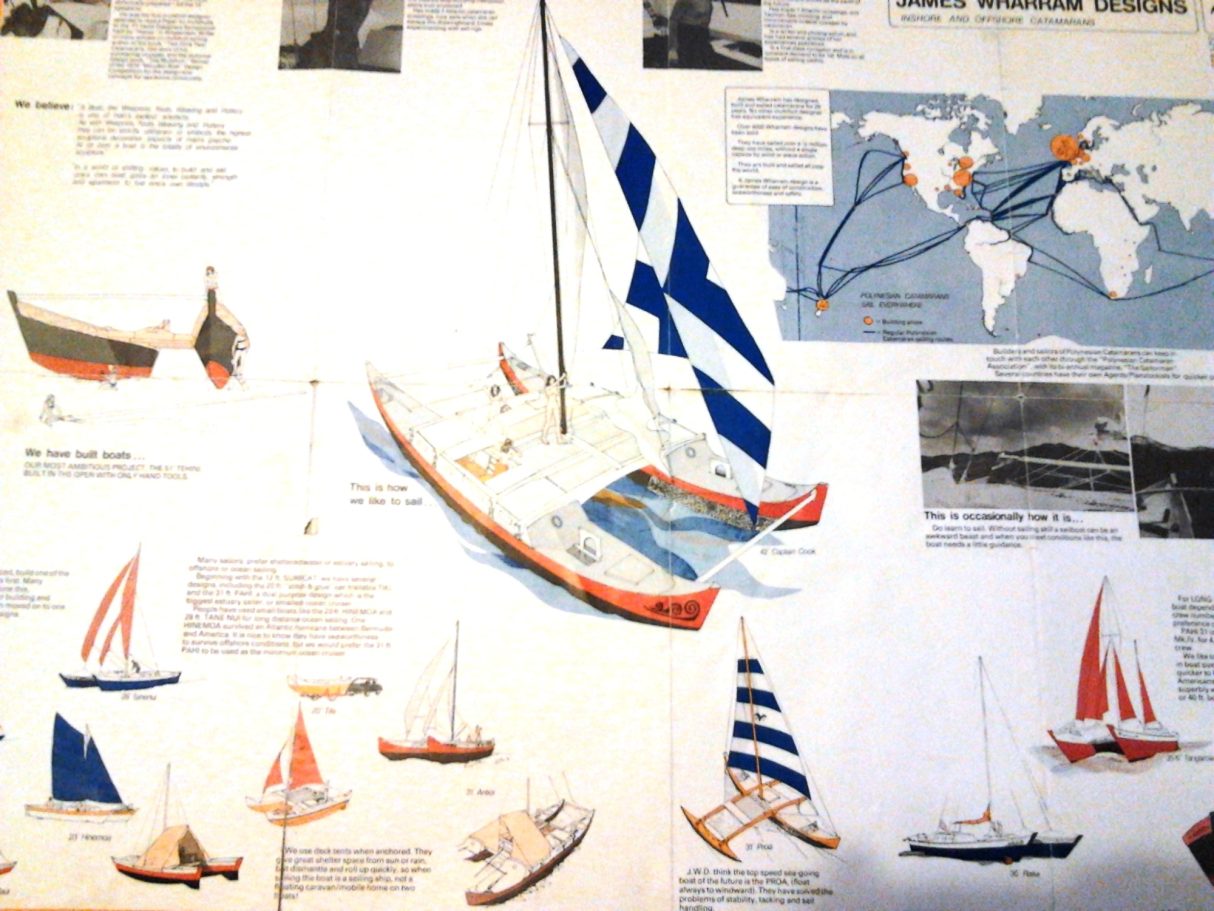

James Wharram (aka Jim and Jimmy to his friends) is also sometimes described as the father of the modern multihull but that is not entirely accurate because as we are seeing the World was full of people developing mould breaking revolutionary multihulls and very few of them owed anything at all to Wharram's designs which were always different from the mainstream.

Indeed I would go so far as to say that the commercially successful multihulls that are so dominant in the World today follow totally different design principles and styles to the Wharram designs which even today are unique albeit that Wharram claimed the distinction of selling more catamaran plans for home construction (over ten thousand) and he and his wives Ruth and Hanneke built a terrific brand with almost cult like success by being very different and always seeking to be controversial. Some say that Wharram sold more than designs and his buyers instead bought into an entire philosophy.

Today Hanneke runs the business with their son Jaime, but such is the way the boating market has changed since the Wharram heydays of the 60's and 70's the market for self-build has declined. A choice to buy Wharram plans to build your boat is now more than ever a lifestyle choice based on sustainability and beliefs. Keen racers and those looking for high performance sailing will not choose a Wharram design, and it must be said that sophistication, and luxury do not apply to Wharram designs either.

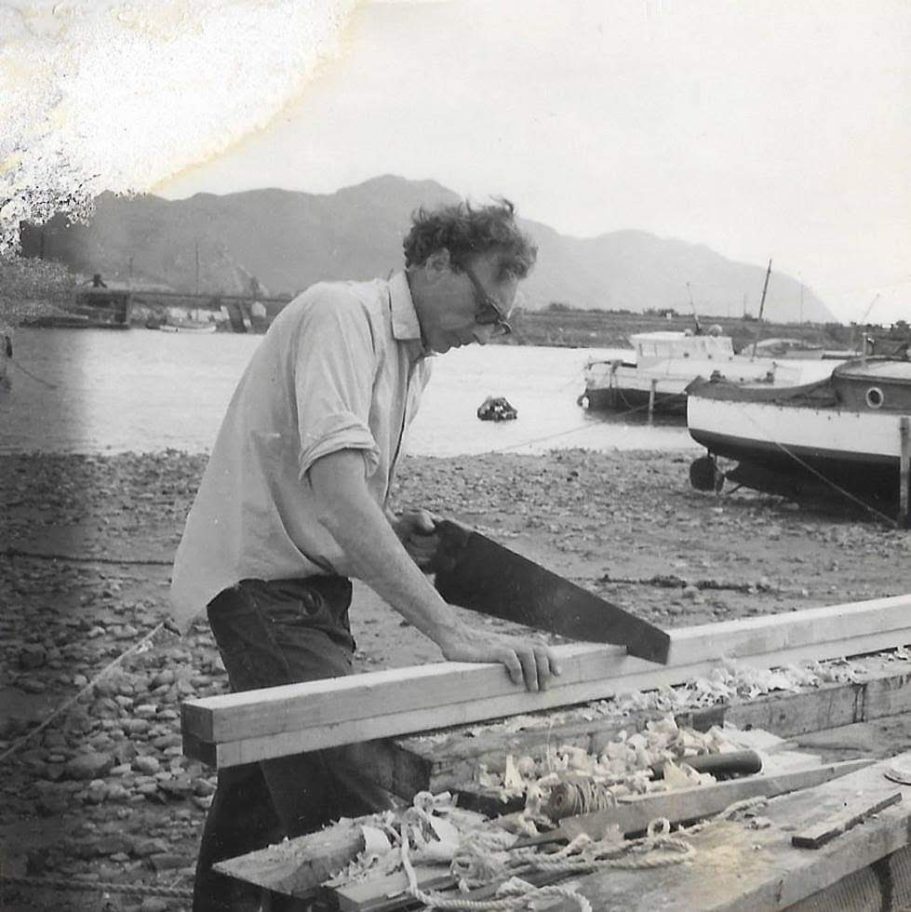

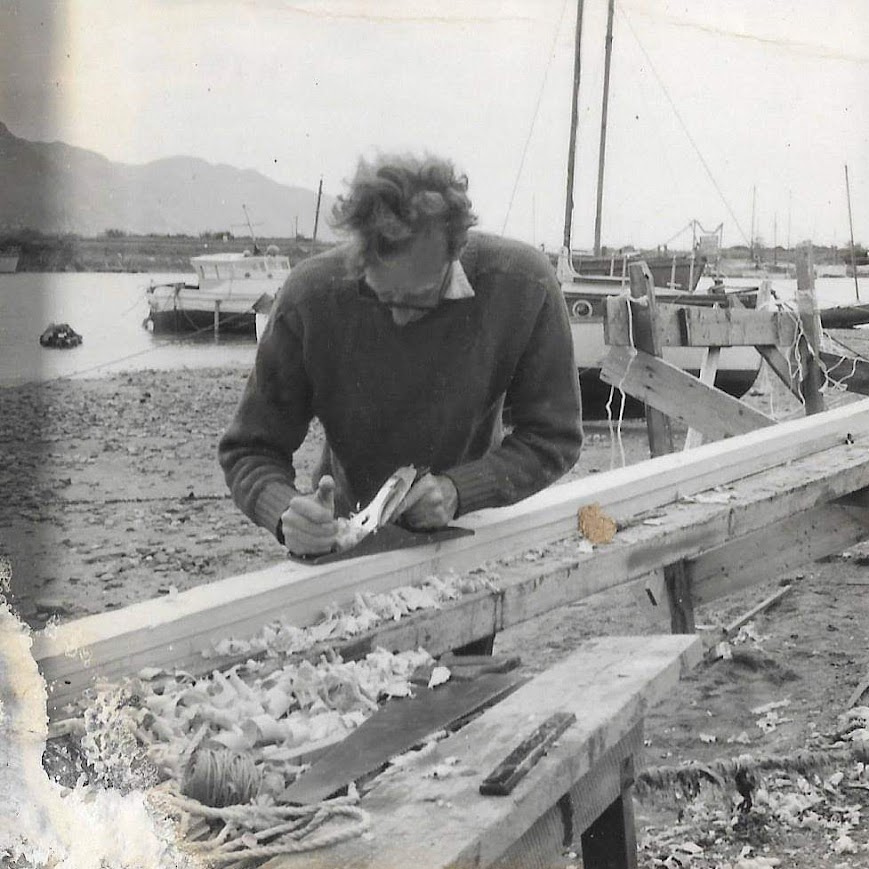

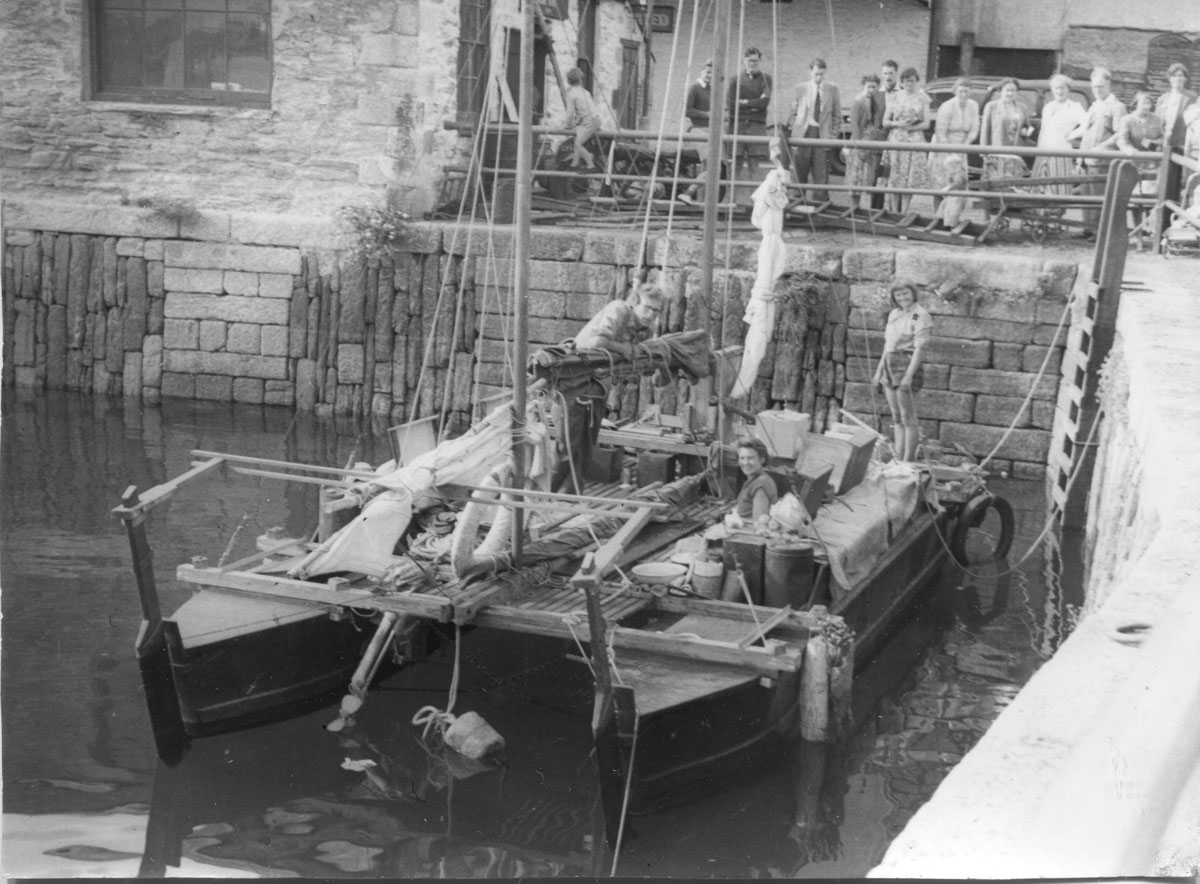

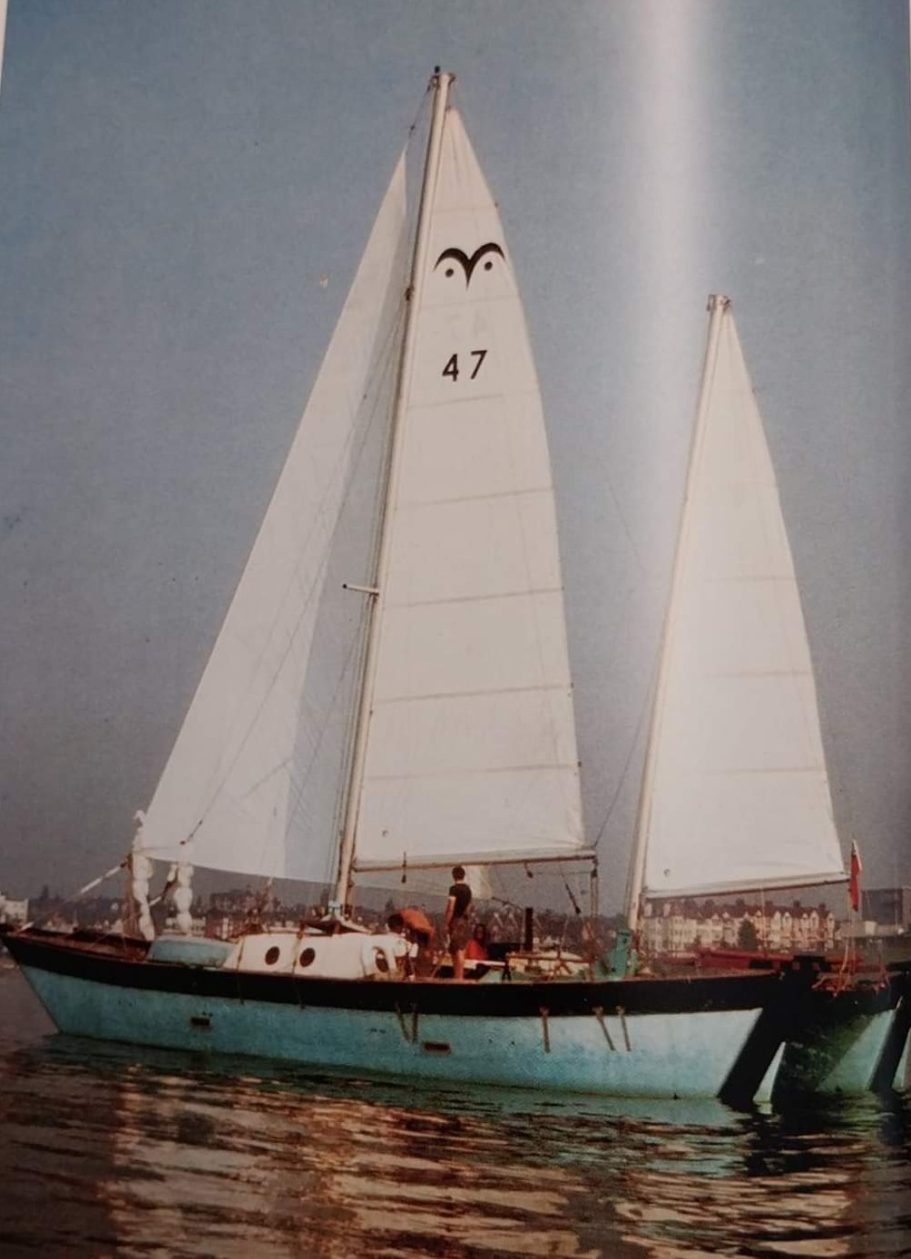

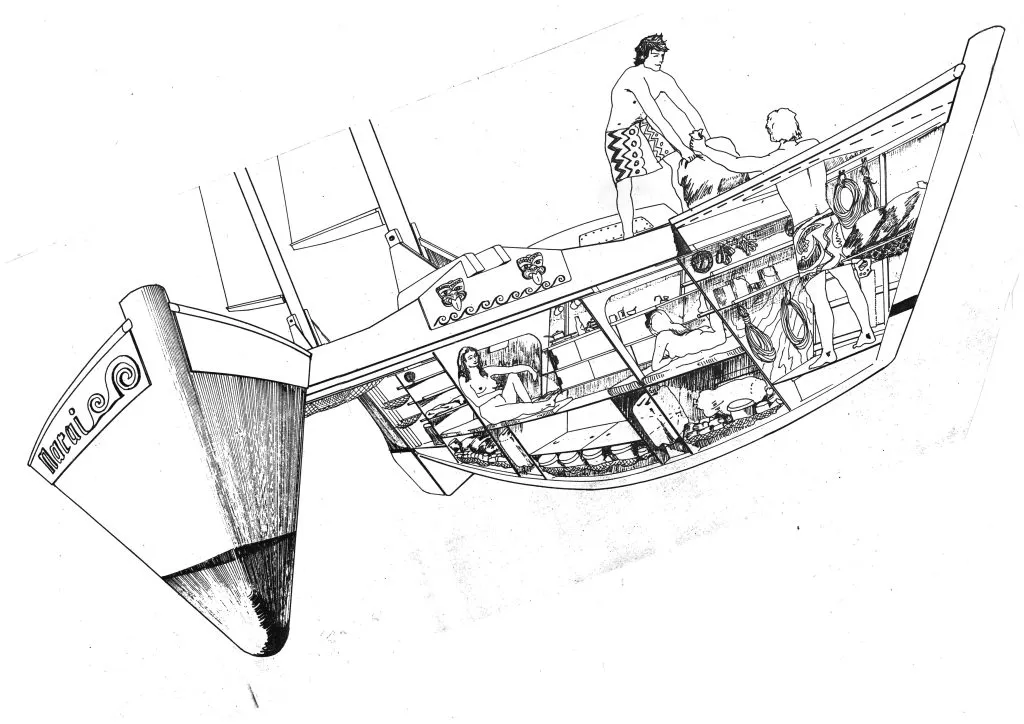

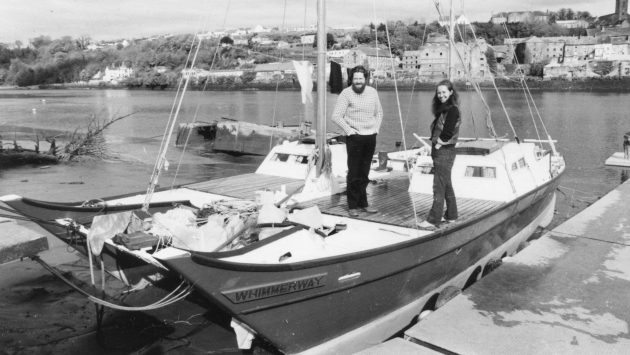

The first Wharram design was the 24-foot Tangaroa on which the three adventurers Jim, Ruth and Jutta sailed to the West Indies. Flat bottomed with a tiny rig and cabins like rabbit hutches and their voyage must rank as one of the bravest in the history of modern boating.

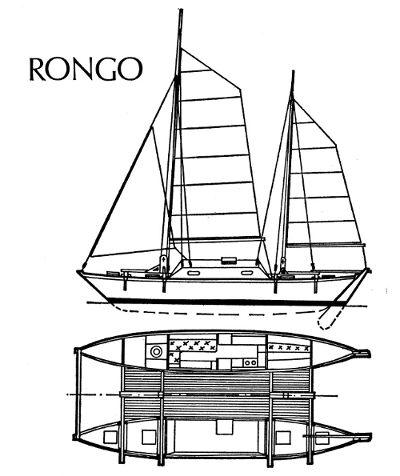

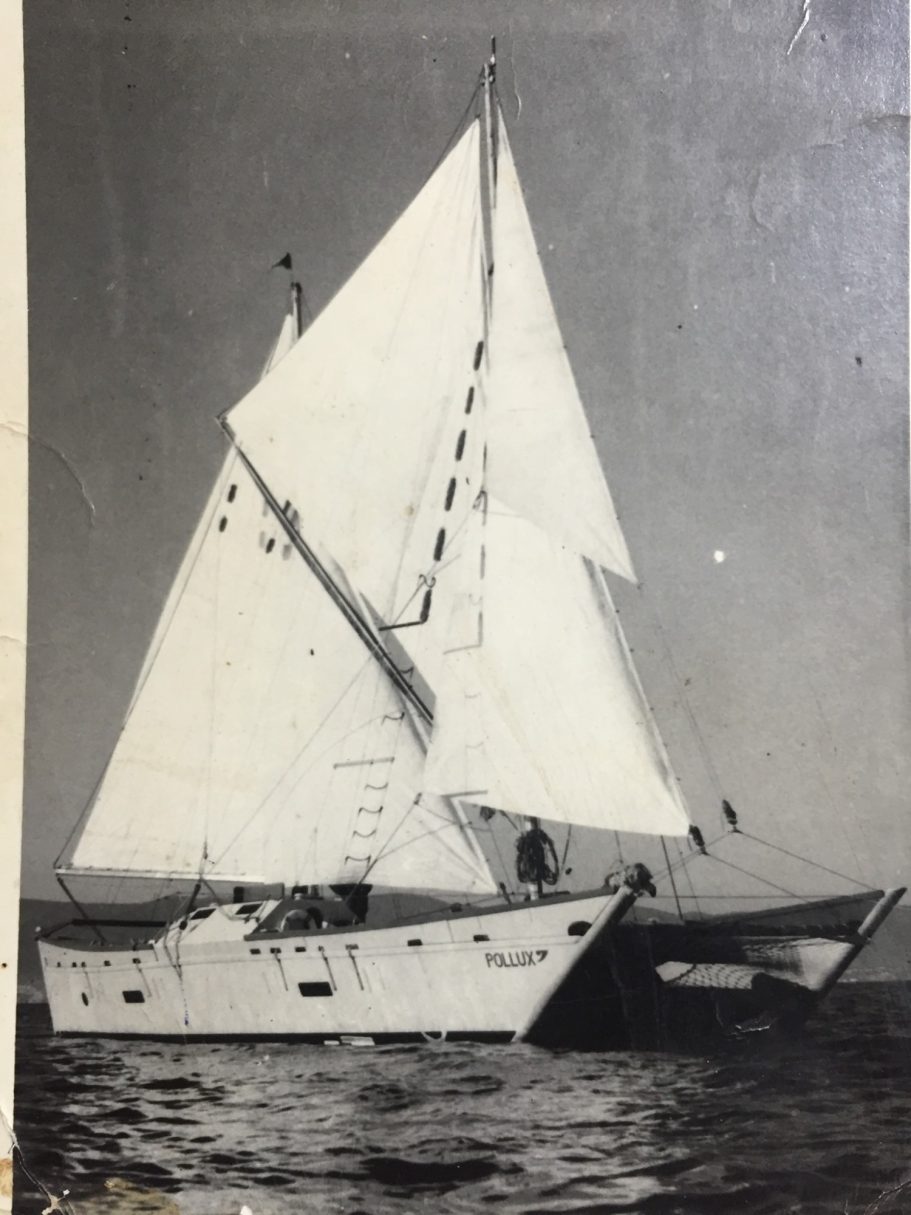

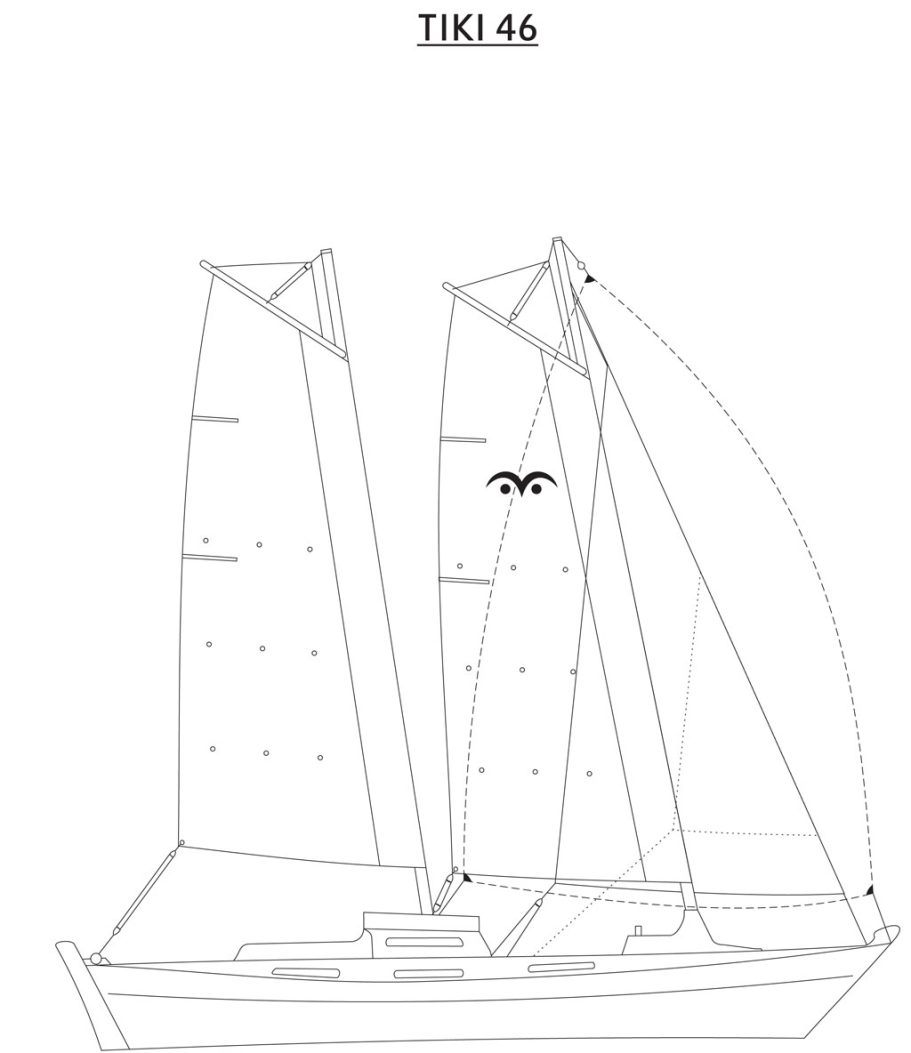

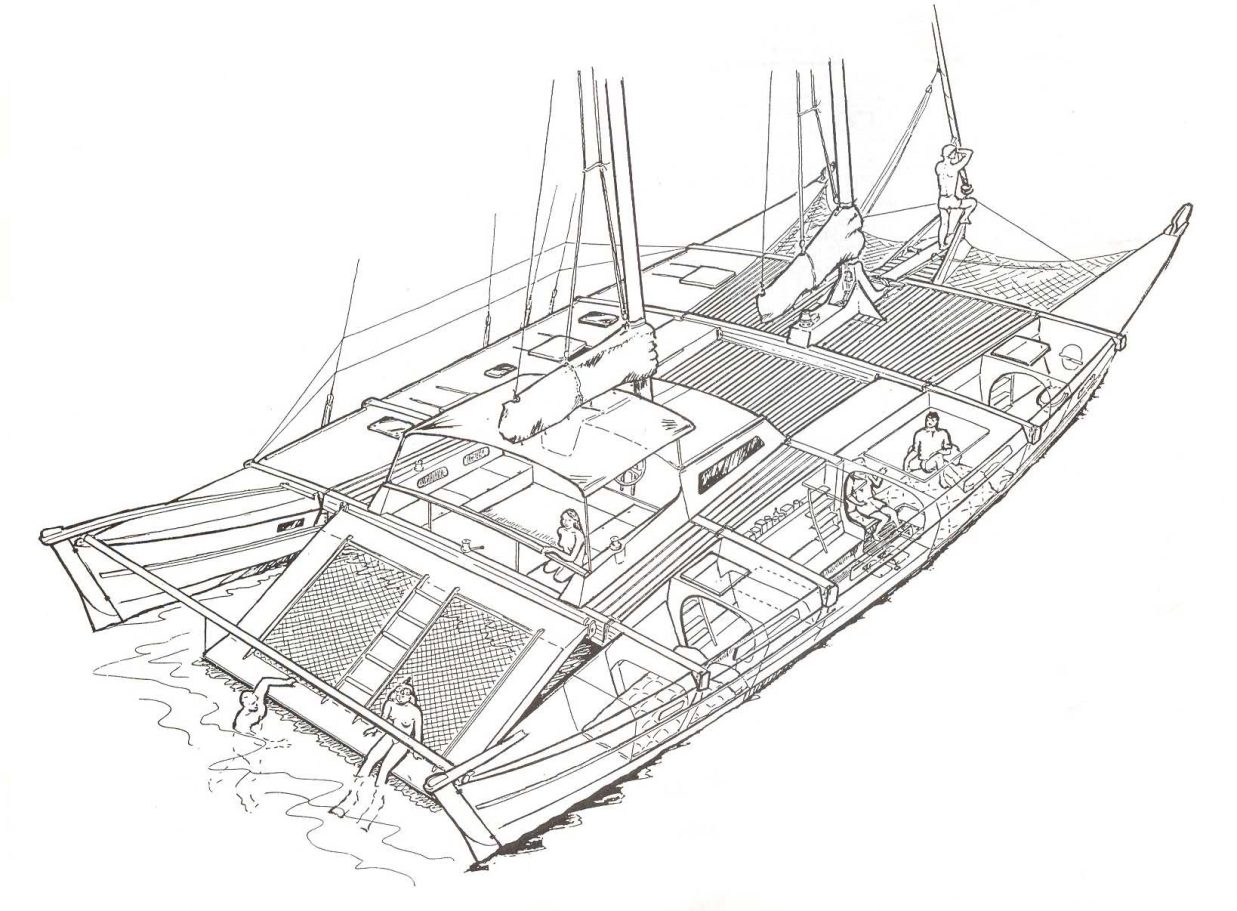

Living on a raft in Trinidad where Jutta had his baby, Wharram’s next design was the 40-foot Rongo. This brilliant design is without doubt the basis for every Wharram since and if you look at her and the Tiki 34 and 46 the family likeliness shines out although the construction methods are now more modern ply epoxy glass sandwich and the build method evolved to be suitable for home builders but so much more sophisticated and nuanced than the designs that Wharram marketed in the 60's.

After a tough voyage from New York to Ireland in 1959 Rongo was readied for around the world voyage. Jame had married Jutta, and they all set out around the World. Jutta’s death by suicide in Las Palmas ended the voyage and Ruth and James crossed the Atlantic to Trinidad before sailing back to Ireland and then Wales in 1962. They had now sailed Rongo three times across the Atlantic covering over 12000 miles in her.

After his abandoned World voyage James and Ruth lived with James' son on Rongo on a beach in North Wales. It must have been a very hard life indeed in a spartan plywood catamaran without any modern facilities, and I have no idea how they earned a living either.

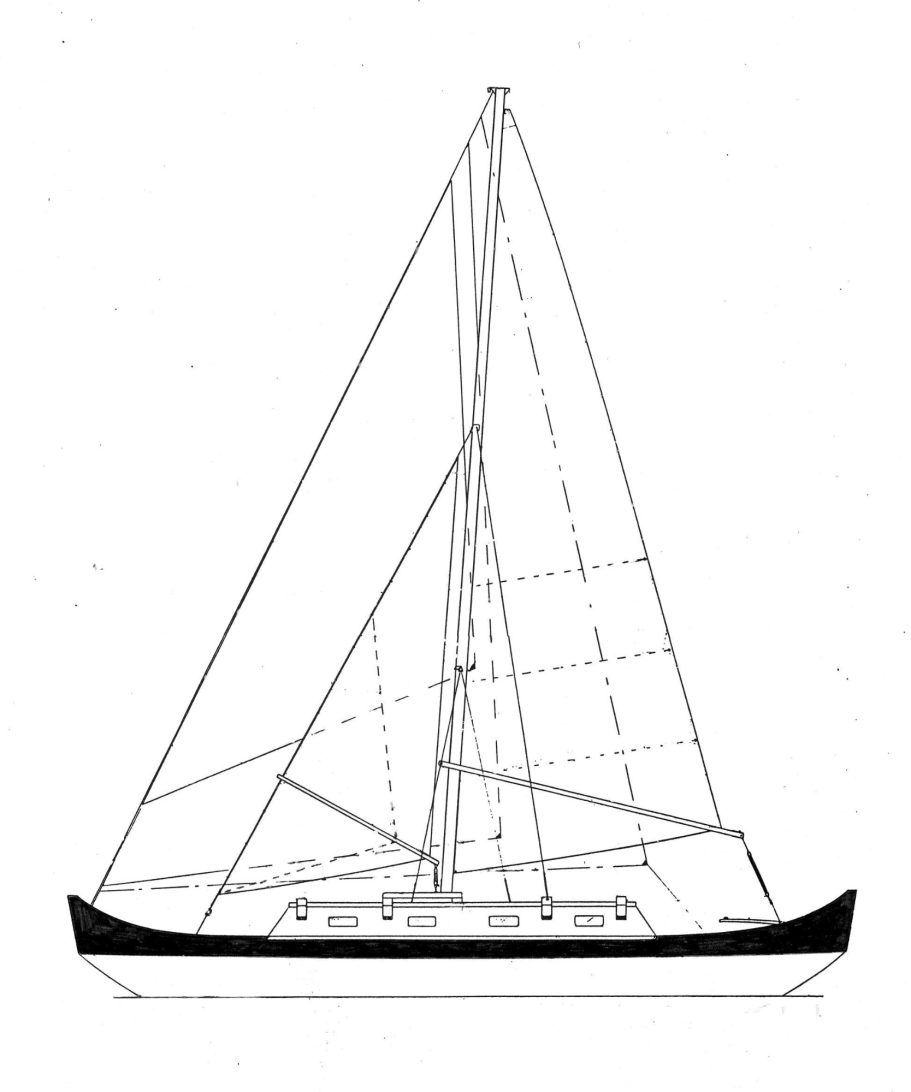

In 1966 James built a trimaran called "Tiki Roa" and took it to enter the 1966 Round Britain Race. Writing to AYRS and Multihull International, his ambitions for the double outrigger were frankly delusional. Its small sprit sail rig and V shaped hulls meant it was not going to succeed as a racer, and it had almost no accommodation either. Post race James abandoned the concept and indeed became very much against double outrigger trimarans as designed by Kelsall, Crowther and Newick in particular.

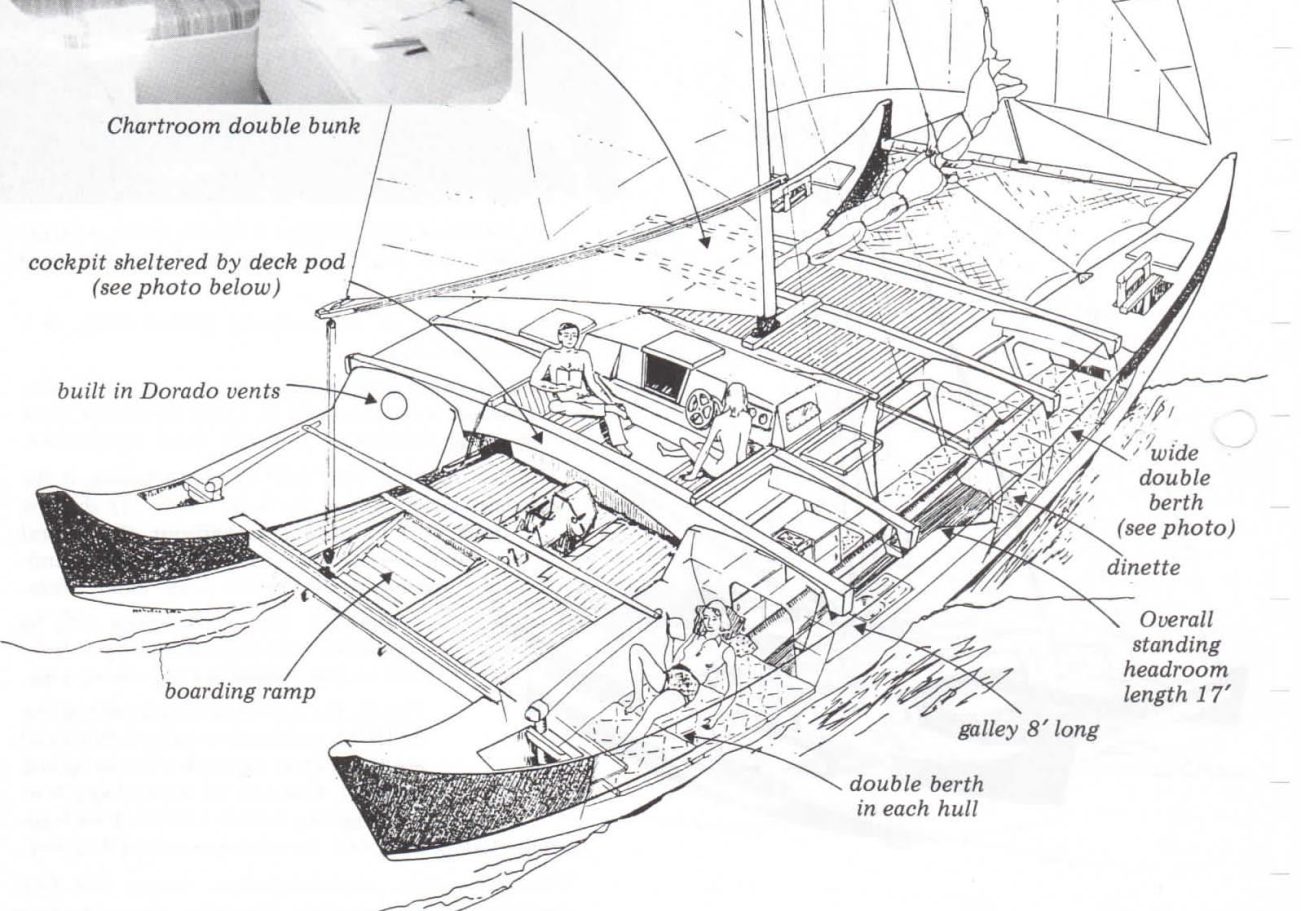

At about the same time he designed a 22-foot catamaran called Hina and a 34-footer called Tangaroa. Both were very crude designs with spritsail rigs that were not a concept that could achieve the high performance sought by most multihull designers. He followed this with the 46-foot Oro and published articles in yachting magazines and his self-build design catalogue started to achieve sales and boats were built, and others sailed the Oceans in them.

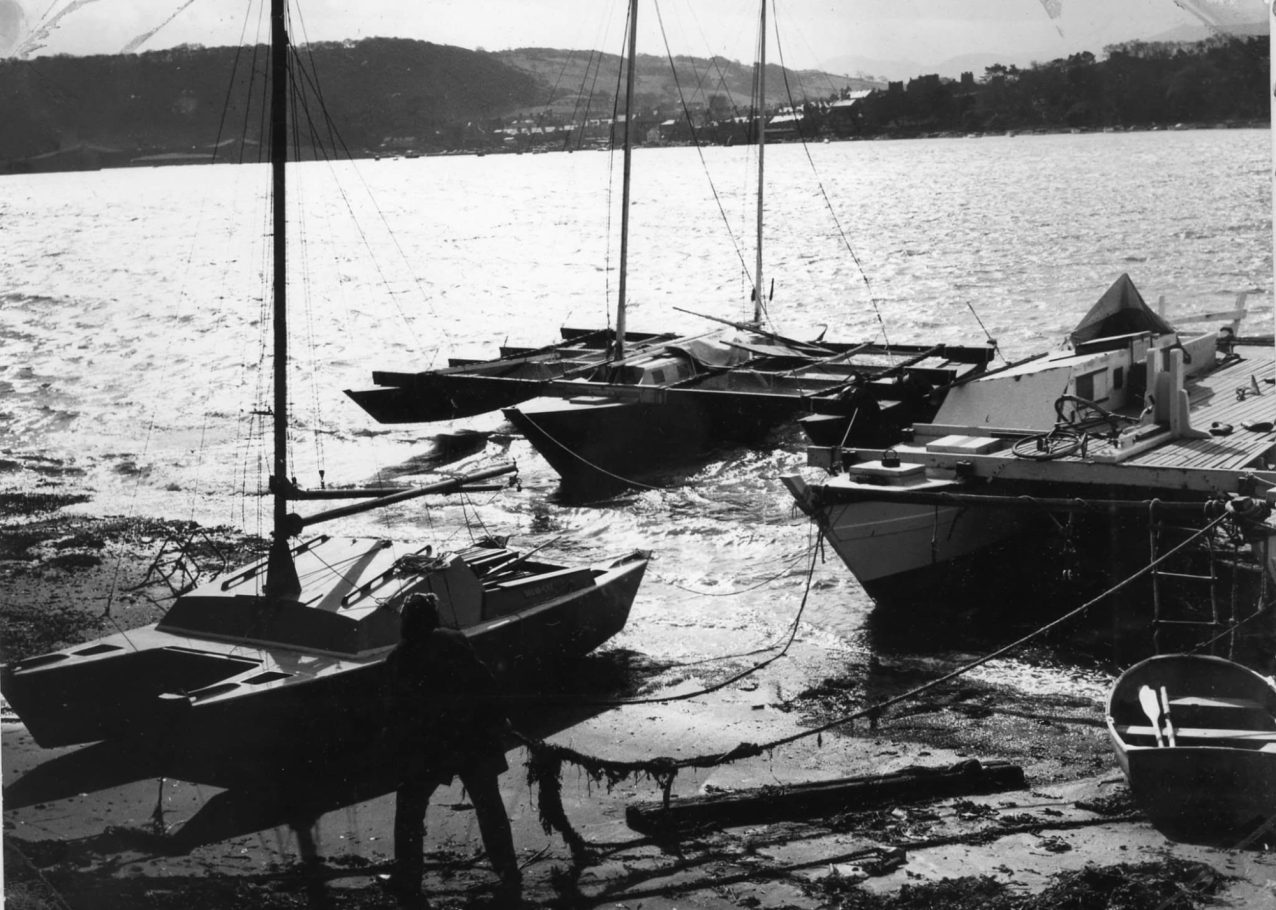

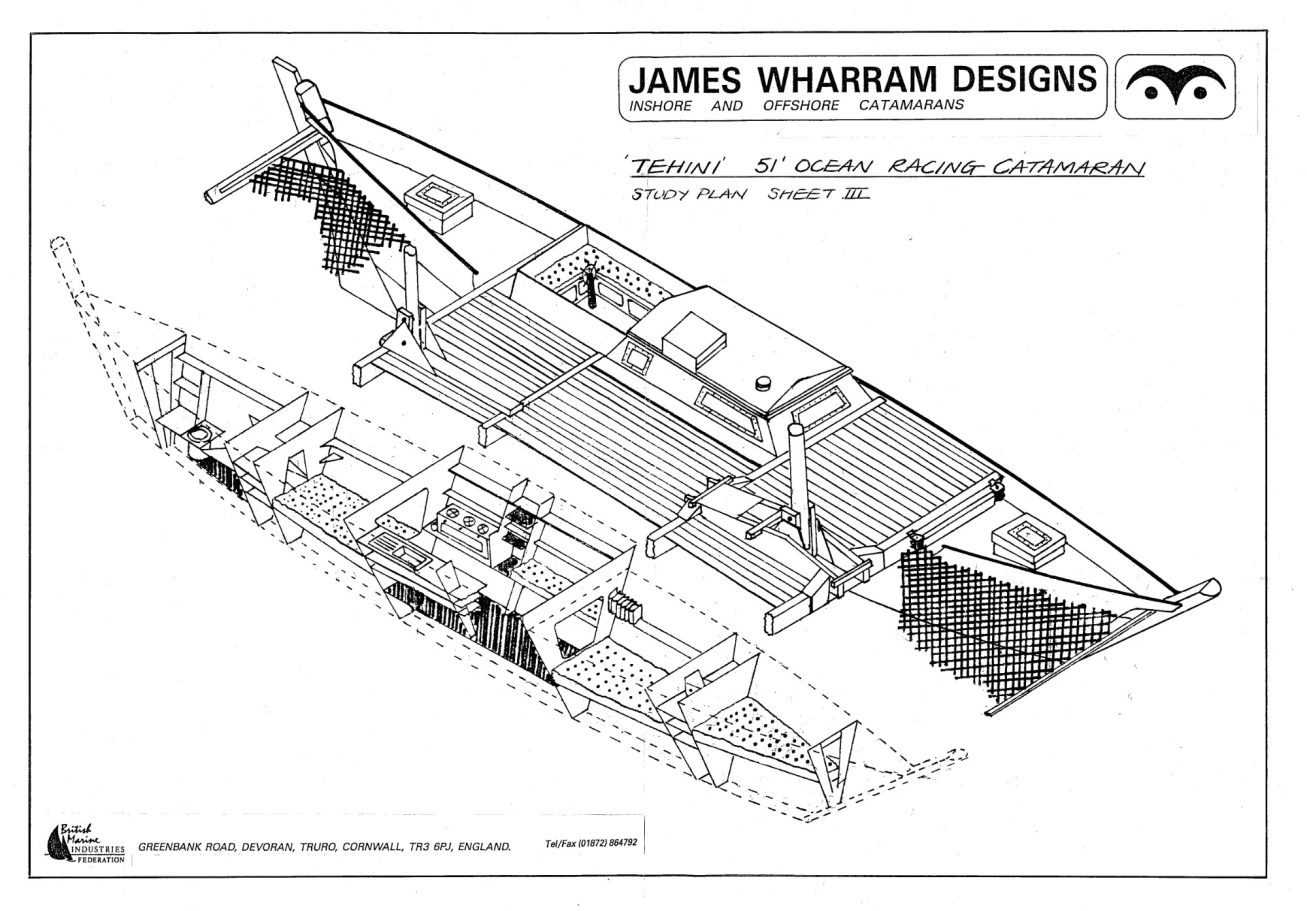

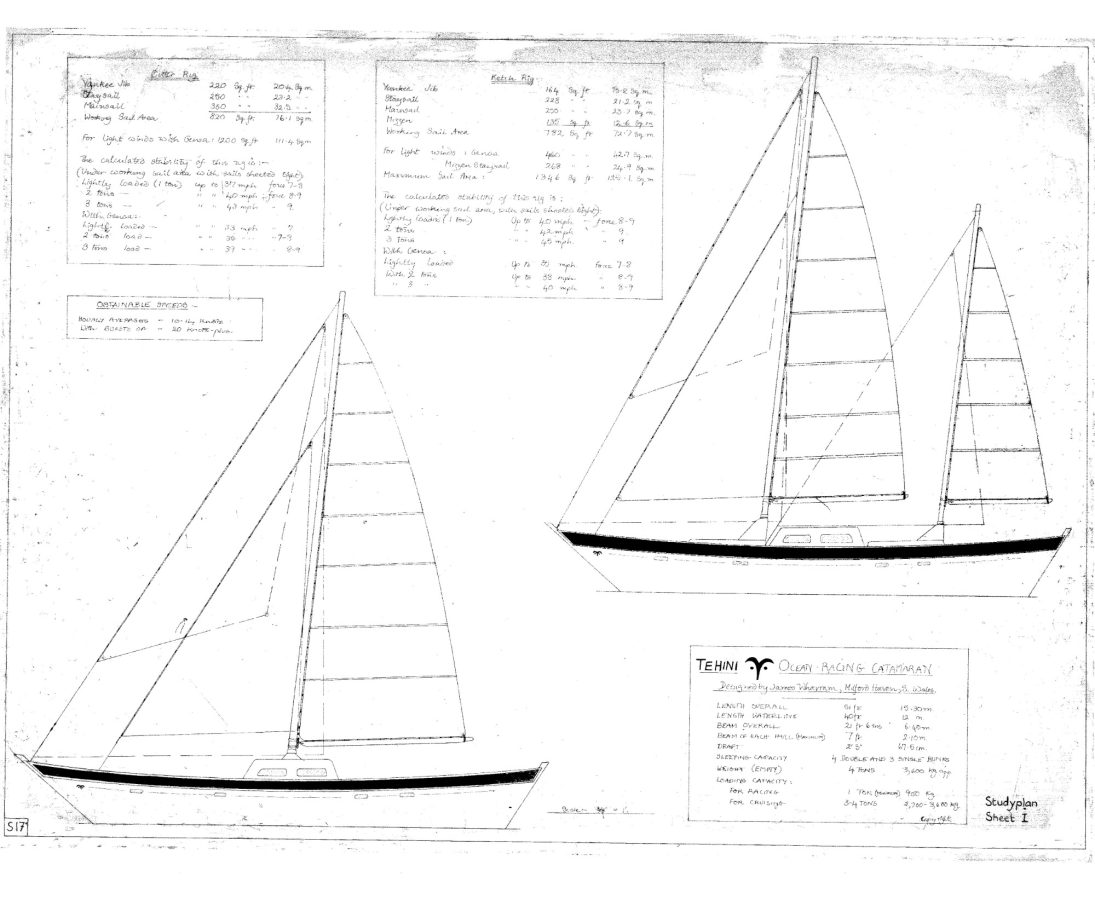

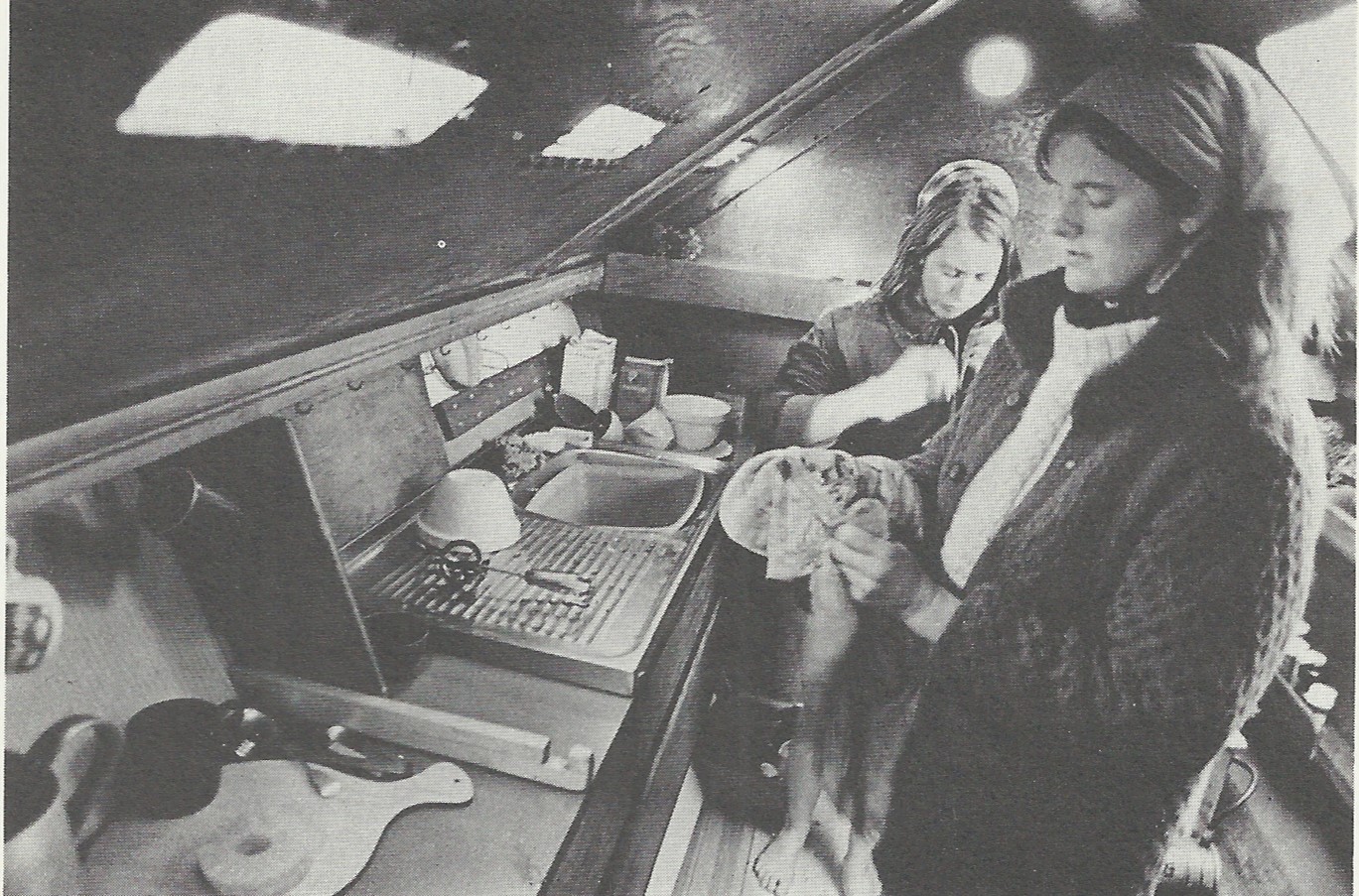

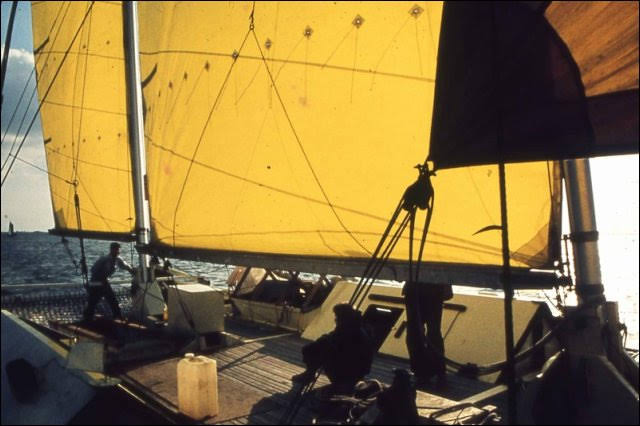

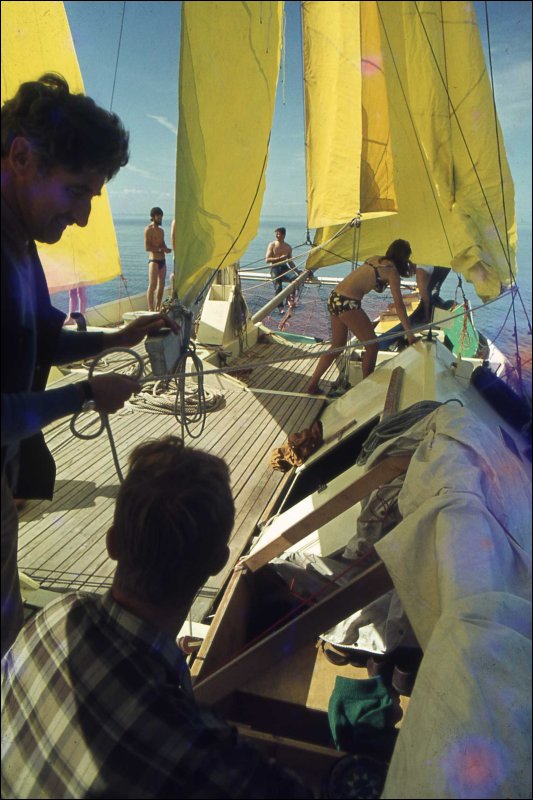

The building of a 52-foot Tehini in 1968 to 1969 took a lot of people's imagination. The film of this made by Ruth Wharram is now available on You Tube. Establishing a commune like existence of men and women around him was an alternative lifestyle which is now branded as being a hippy one and certainly the image of Wharram catamarans was one of hippy boats. Wharram wrote a lot about his view that the modern consumer society was doomed in the 70's. His philosophy of escape to live on sea communities fitted into the whole self-sufficiency movement of the 70's and Wharram was still preaching it and the pleasures of multiple relationships, sexual freedom and naturism into the 21st century.

Between the 70's and 80's the Pahi range was evolved too with hull shapes chosen to resemble genuine Polynesian concepts something they took further in the voyaging canoes they built for the 2008 Lapita voyage which was the antithesis of Heyerdahl's Kon Tiki expedition and proved the viability of double canoes with hulls based on examples of native canoes with traditional Polynesian style sails migrating East to West to Polynesia.

In the 1990's Wharram and his wives (he always lived polygamously although married first to Jutta, then Ruth and lastly after Ruth passed away to Hanneke) sailed around the World in the 63 foot Spirit of Gaia although they were rebuffed when they attended a Polynesian voyaging rally where the Polynesian did not appreciate the English cultural appropriation of their traditions by a white Englishman. Wharram lived his entire life fighting the "establishment" on behalf of ancient Polynesian concepts and to suffer discriminatory exclusion by those same people must have been an awful experience for such an enlightened man.

Studying the journals of the AYRS, the pages of the UK's Multihull magazines and later the popular yachting press which finally started to appreciate Wharram in the 70's he shines out as a very opinionated character who seemed to be determined to pitch himself against convention at every level in his designs, his personal life and his confrontational approach.

While the UK yachting community bought the grp catamarans from Bill O'Brian, Prouts and Sailcraft with their comfortable bridge deck cabins, Bermudan rigs, keels and centreboards and the trimarans of Piver, Kelsall and Crowther, Wharram railed against these concepts arguing the superiority of his plywood V shaped hulls, open slatted decks and lack of any protruding boards or keels. When he could not claim superior seaworthiness, he could say his designs were cheap and easy to build and he promised ordinary people the ability to build boats and live a fantasy-like lifestyle as "sea people".

The books "Two Girls, Two Catamarans, in 1969 and "People of The Sea" in 2020 tell the story but as often with autobiographical writing I am left wanting to know so much more.

In the late 70's there was a series of capsizes involving trimarans which following the success' of Kelsall, Crowther, Newick, Shuttleworth and Andrew Simpson were riding high. Tabarly, Tom Follet, Walter Greene, Phil Weld, Alain Colas and the amazing Mike Birch were winning ocean races and they all raced double outrigger trimarans. The prospect of wave induced capsize was an issue. The development of multihulls was still experimental. Outrigger buoyancy and the shape of the hulls, and the volume of the hulls were still being developed. Wharram and Hanneke wrote an article on stability that concentrated on the idea that sail areas should be kept low an idea James had argued consistently as early as 1967 after the CSK catamaran Golden Cockerel capsized in the Solent while racing. They espoused a theory that only double outrigger trimarans were subject to wave induced capsize which was far too simplistic. The problems of roll inertia caused by the heeling of trimarans and low buoyancy outrigger floats certainly produced some wave capsizes but many combinations of wind and waves caused other multihull capsizes too. Starting in 1968 James sold designs like Hina, Tangaroa, Narai and Oro were very simple with low rigs, and tiny cabins. Many were built by inexperienced “Wana be” sailors, and they did not always have the seamanship skills to sail the boats resulting in some disasters. However, many of the builders were able to achieve long ocean voyages all around the World. From the early 1980s after his life in Ireland with five women in a commune failed and he broke up with all but Ruth and Hanneke, James moved to Cornwall for the last 40 years of his life and designed small day sailing catamarans starting with the Tiki 21. He marketed the idea of holiday escapes and weekend sailing for people who did not reject land-based lives with jobs. Throughout his life James pitted himself against the mainstream and was critical of luxury catamarans which dominate the multihull market saying they were for western "land" people who wanted a boat that was like their apartments. He was very critical of designs that could capsize easily because they were over canvassed, but the reality was that his designs could capsize too when owners or builders enlarged their rigs to improve speed and windward performance. The Wharram tenets of flexibly connected hulls, low multi masted (most were ketches or schooners) and often gaff rigged or at times junk rigged or using a version of a Polynesian sprit sail (and in his earlier designs using the spritsail itself) . The lightweight Tiki 21 and 26 models were both capsized in the hands of crews that did not appreciate that they had limits; this is true of most multihulls that inexperienced sailors or contrarily experienced mono hull sailors fail to detect that they are on their stability limit because they do not heel over. . Wharram never changed his opinion that multihulls had to be sold as safe family boats and freedom from capsize was an essential starting point. He could be quite forthright and was clearly not a man to suffer fools gladly particularly when those fools were his competitors like Arthur Piver, Derek Kelsall, John Shuttleworth and Richard Woods all of whom he criticised for being "city men" and that he thought put speed over safety from capsize to sell designs. James dismissed the arguments that multihull development was to be found in test tanks and computer programs and preferred to look to principles he derived from study of Polynesian designs and empirical sailing experience for all the answers. Relying upon his own experience and voyages he claimed to know what made multihulls seaworthy because of his sailing - a view which of course did not give credit to the experience and ocean voyaging of other designers particularly Piver, Kelsall, Newick, Crowther and Shuttleworth all of whom had long voyages, and had also done trans-Atlantic's and other sailing experience that distinguished them as sailors who designed boats. James always established his credentials based on his Atlantic crossings and implied he had more Ocean experience than others. Perhaps the others chose to be more modest about their seagoing experience because they were also aware that their knowledge and expertise was very much evolving and it is evident particularly in the writing of Kelsall, Shuttleworth and Newick that they were aware that they still had a lot to learn. Pat Patterson for example was famous for his bestselling Heavenly Twins family cruising catamarans, but he had sailed extensively with two circumnavigations and several Atlantic crossings to his credit in his own designs about which he was incredibly modest. Comparing the state of the art in multihull design in the 60's with what is being designed and built now shows that the view that multihull design development had a long way to go in the 70's was quite correct.

But throughout his career James clung to his design principles established in the 50's of V shaped hulls, open slatted decks and canoe sterns with flexible beam connections. That said James’ sales success, the number of boats built to his plans and above all the number of voyages made in his designs are his epitaph. Many people empathised with James' values and his political, philosophical and lifestyle ideas teamed with his devotion to Nature and learning lessons from Stone Age sailors to build boats that owed nothing to modern mainstream yacht design.

My limited experience of meeting him was about 22 years ago and I was happy to find that rather than the outspoken, opinionated and controversial man that I though he was, in person he seemed very approachable, and charming and he clearly had that effect on many that he met. He was seen by some as a "great" guru like figure. I do believe he cultivated his role as the great Jim leading his tribe of Sea People to a better place than suffering in mainstream wage slavery. The early journals of the Polynesian Catamaran Association are available online and are an interesting read. They tell the story of how James gathered many aspiring catamaran sailors and builders to his designs. He had a vision of a great body of people sharing their experiences and voyaging and sharing the results. Sadly it did not quite work as he so inspirationally wrote. Some sailors of his designs lacked skills and experience. Unlike many designers he seems to have encourages his builders to be creative with the designs too which produced some odd interpretations of the plans -some more successful that others which caused breakups at worst and ugly aberrations of the designs. The film about the building of Tehini shows that the craft was rather roughly built with tar all over the hulls and roofing felt and tar used on the decks -not something you would see at Camper & Nicolson! The strange triangular cabin tops made her look very homemade and indicate that she was indeed built to a very tight budget. It is no surprise that the vessel was very short lived launched in 1969 she was deemed too rotten and unsafe to sail by 1985 and in about 1990 she was burned. Wharram's Rongo had been built in 1957 and was effectively a houseboat on a beach ten years later. In 1969 James gave her away to the Sea Scouts who sank her. when they tried to take her to sea. But some builders assembled beautiful craft to his plans and the Spirit of Gaia was built to professional standards and sails in Portugal under Hanneke's command.

Petty quarrels in the Association and disappointing editors that came and went were an issue and eventually after the collapse of "James Wharram Associates" in Ireland James, who saw himself as terribly betrayed at the time although by the time he wrote his final book in 2020 he or Hanneke who co-wrote it, was able to see where a lot of the blame lay in James himself and his arrogance and a mistaken belief that taking part in the Round Britain Race courting publicity (in 1966, 70, 74 and 78) would give him the credibility and recognition he obviously wanted.

In fact all these racing adventures just showed up the shortcomings of the Wharram designs, the disastrous trimaran in 1966; Tehini would not go to windward with her junk rig in 1970 and abandoned the race again on the first stage; in 1974, Maggie Oliver one of his closest female companions sailed her and suffered the structural failure of the main beams and retired citing blown out sails; in 78 a grp foam sandwich Tane Nui started to fall apart with major structural problems and the 35 foot Pahi prototype proved so wet and exposed her crew had a terrible time and finished well down the fleet as one would expect for a boat with no keels and just small ineffective dagger boards and a tiny rig.

James took over running the PCA in 1982 editing the Sea People Magazine himself. The association came back to life although there were rumbles that the breakdown in the association was caused by James because its editor decided to open up to other influences especially the Multihull Ocean racing and Cruising association. Other designers were also influential in the home build market like Kelsall Shuttleworth and Wharram's former protégé Richard Woods who had started up in competition (as James saw it). Kelsall was also marketing his own range of self-build designs in GRP foam sandwich. In time James handed over the PCA to others having believed that he had got it back up and running. Unfortunately, this developed into a dispute because James felt he was having his own business stolen by others who took up roles in the PCA and built their own website and business around Wharram catamarans.

Others portrayed James as the controlling personality but the reality was that James' idealistic ideas for the PCA did not work because the whole enterprise cantered on the idea of James Wharram and that the boats were his concepts and designs.

While James had been busy throughout the 1990's both running his own professional production business and sailing around the World in stages he believed that others in the PCA had started to build their own business about the Sea People community dream and also "improved" the designs creating their own rigidly monocoque versions some with the deck cabins he so loathed and so James was forced to take legal action (he told me) to protect his business identity and his intellectual property rights to 'Wharram Catamarans'. This dispute and the arrival of the Internet really killed off the PCA. However what has grown up in its place over the past 25 years is a big community of people sharing stories of their Wharram Catamarans, their experiences building them and sailing them, on several social media and Internet sites. It seems that the spirit of what James intended when he formed the PCA in the 60's is alive and well in a thriving Wharram interest community like nothing else in the multihull world.

It must be said that Wharram's wooden catamarans suffered extensively from rot due to what was essentially poor design with metal fittings and bolts being breeding points for water ingress and rot. By no means were they the only plywood multihulls to suffer rot because this type of construction especially back in the 70's before epoxy resin took over, is afflicted with rot when water ingress occurs. But also, the primitive low aspect ratio rigs and lack of keels meant that close winded sailing and powerful windward ability were never really attainable by Wharram catamarans. Strangely James was never a designer who drew his own designs. He would imagine what he wanted and was a boat builder, but he relied upon his associates and later Hanneke to do all the drawing of the plans and Ruth and Hanneke did all the mathematics.

Later designs tried to address this with careful epoxy sealing of all the holes and lashing to avoid the metal bolts and fitting that caused rot.

James wrote copious articles and papers with the help of his associates which with his books leaves a great record of his ideas. By the mid 1990's he and Hanneke produced their best designs after the Pahi 63; the home build Tiki 34 and 46 and the Islander professional designs. Later they developed especially "ethnic" designs like the Wanderer and Mana 24 a kit boat.

His final book People of the Sea is a fabulously produced gallop through his eventful life which encompassed great self-belief, courage, and the consequences human flaws too.

Sadly, as old age and dementia caught up with him, he was brave enough take his own life which in the context of Assisted Dying coming into UK law in 2025 shows that James was in many things a man well ahead of his peers.

James may not have really invented modern catamaran, but his story is heroic and unique to World multihull development. What he did was brilliantly promote his own types of multihulls (he designed catamarans, at least one proa and a trimaran) and his personal design concepts that are unlike any others. But above all James personified the spirit of adventure, self-sufficiency, and striving to live the life you desire. His individuality made him stand out and he clearly struck a note that many people were attracted to and was a most influential and inspiring character.

Arthur Piver

American Pioneer 1910 to 1968

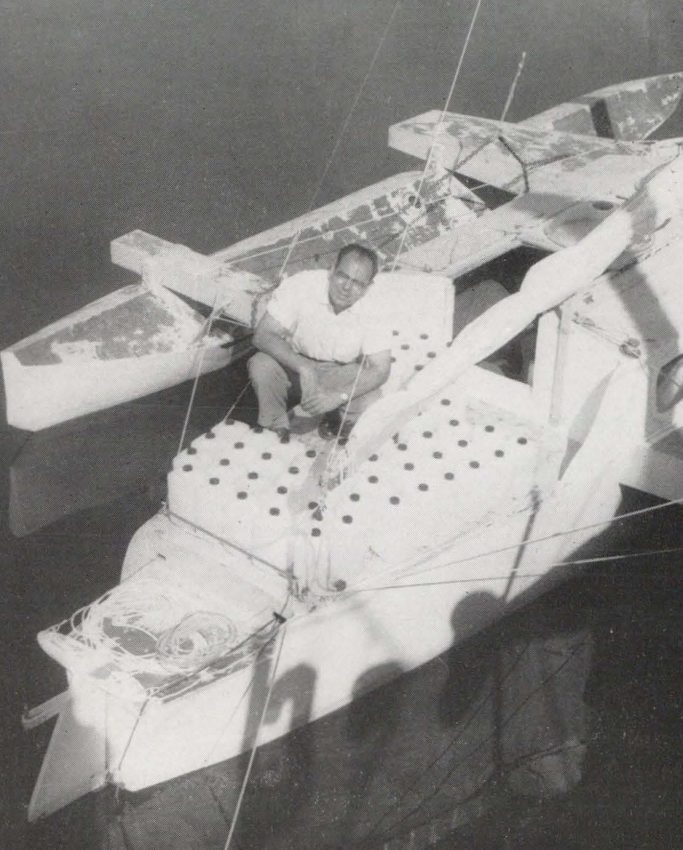

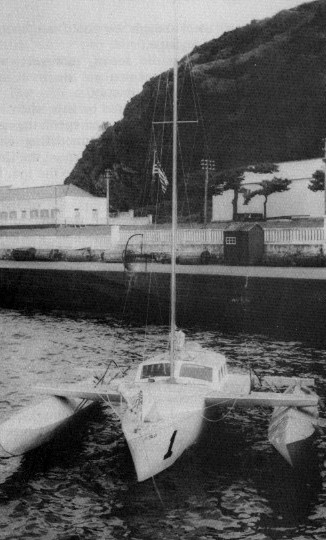

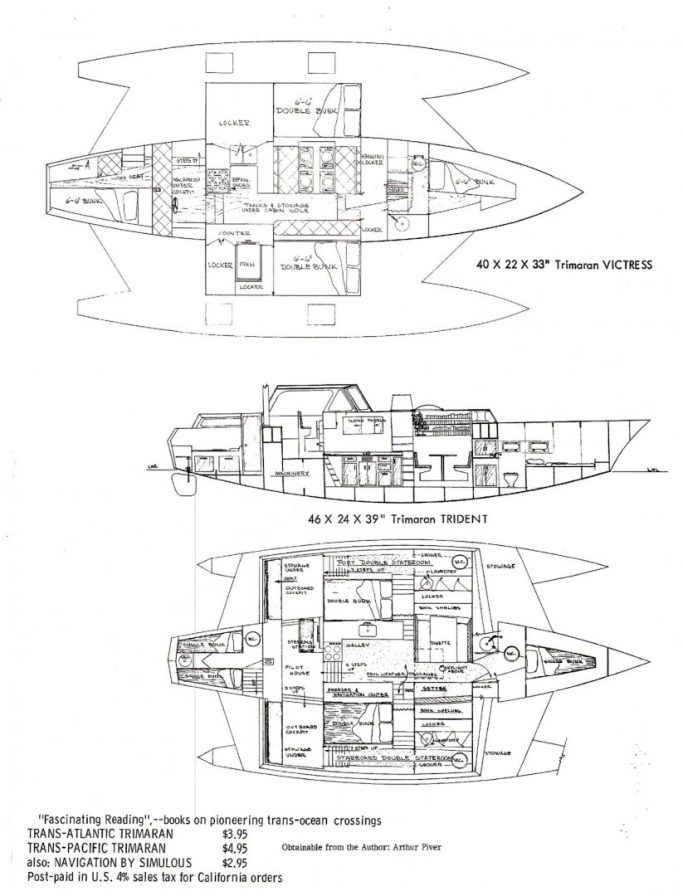

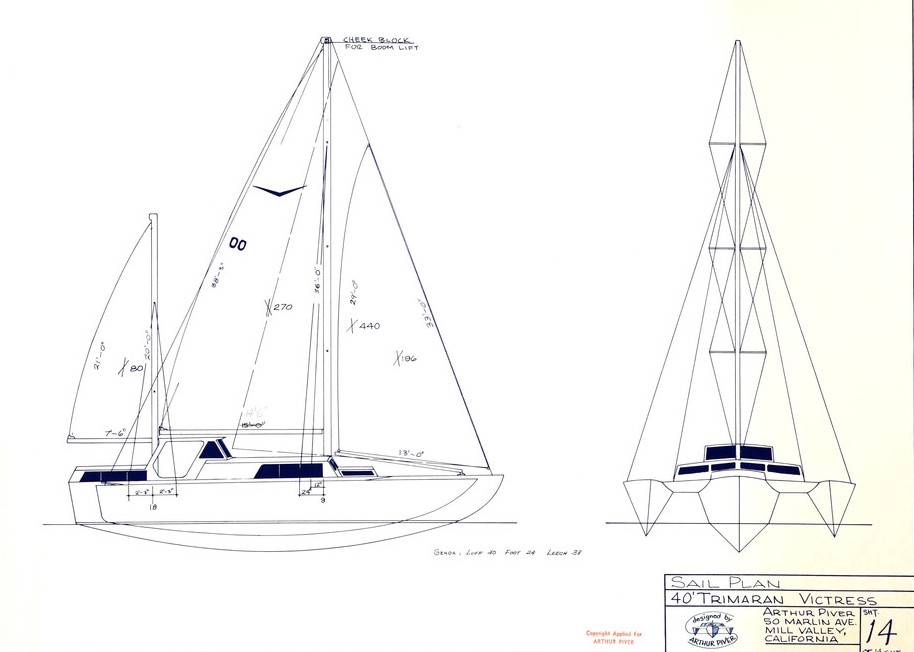

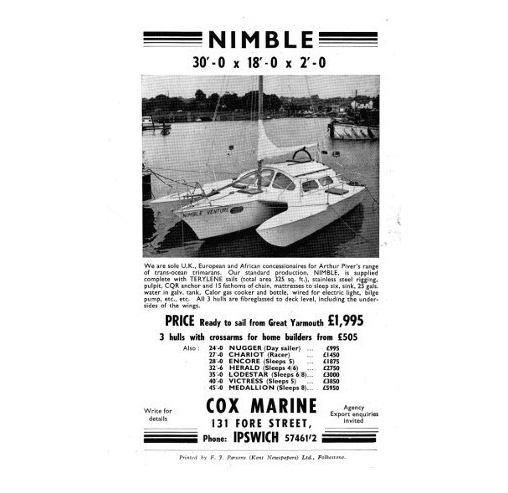

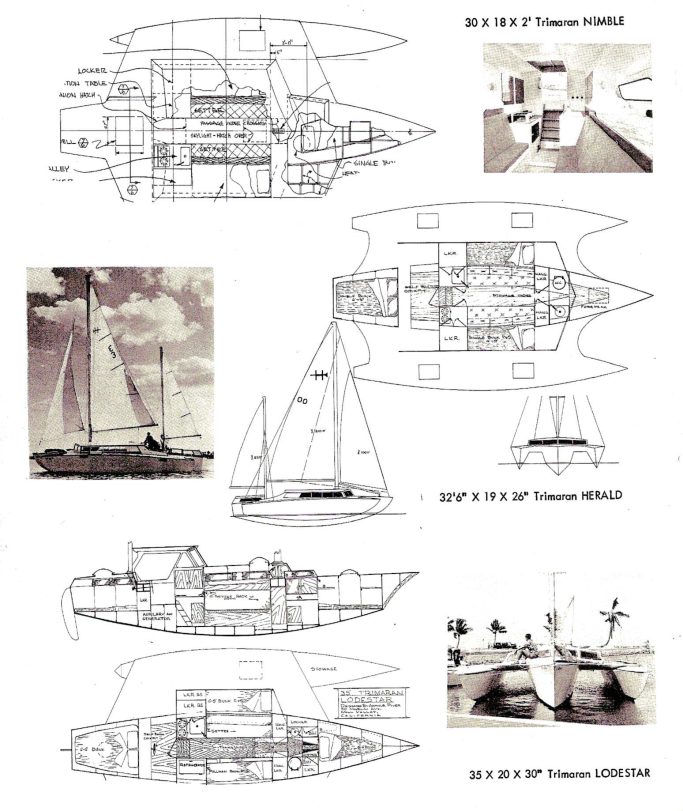

An almost "evangelical" advocate of trimarans was an American called Arthur Piver. He sailed his trimaran Nimble across the Atlantic in 1960 and in 1962 sailed to New Zealand from San Francisco. Piver had a massive impact and in the 60's and 70's hundreds of his trimarans were built by amateurs and professionals. Born in 1910 Piver was a pilot in WW2 and after the war he owned a printshop and was a keen amateur sailor. In the 50's like many others, he started to experiment with catamarans and trimarans and may have been inspired by the progress of Victor Tchetchet who had tested his trimarans in Long Island in the 1940's. Certainly in 1957 he designed and sailed a 20-foot catamaran-his first design, called the Pi-Cat. in about 1953 Piver had built and sailed a small commercial catamaran called a Lear Cat but decided he could improve on it.

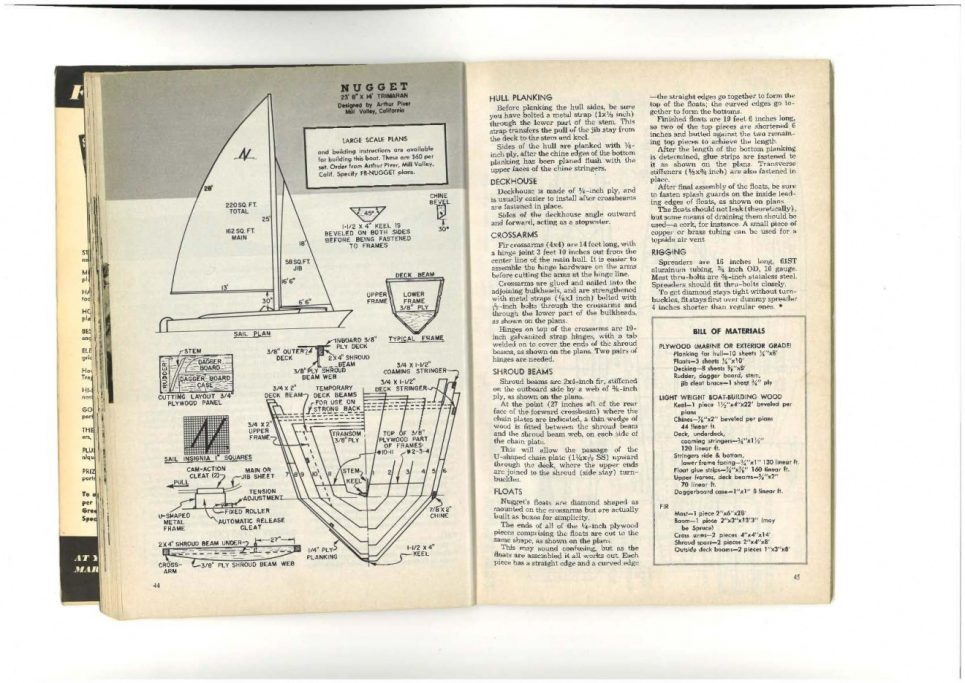

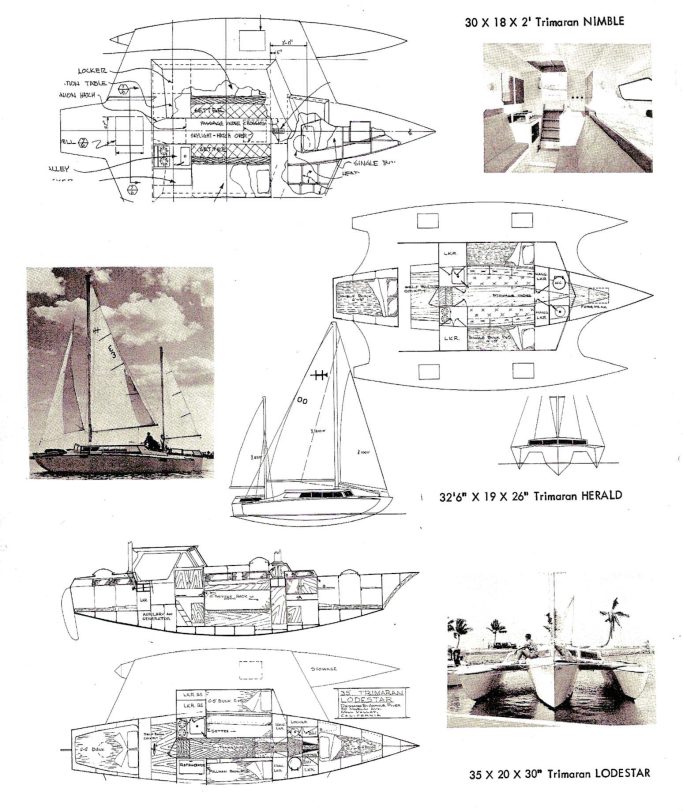

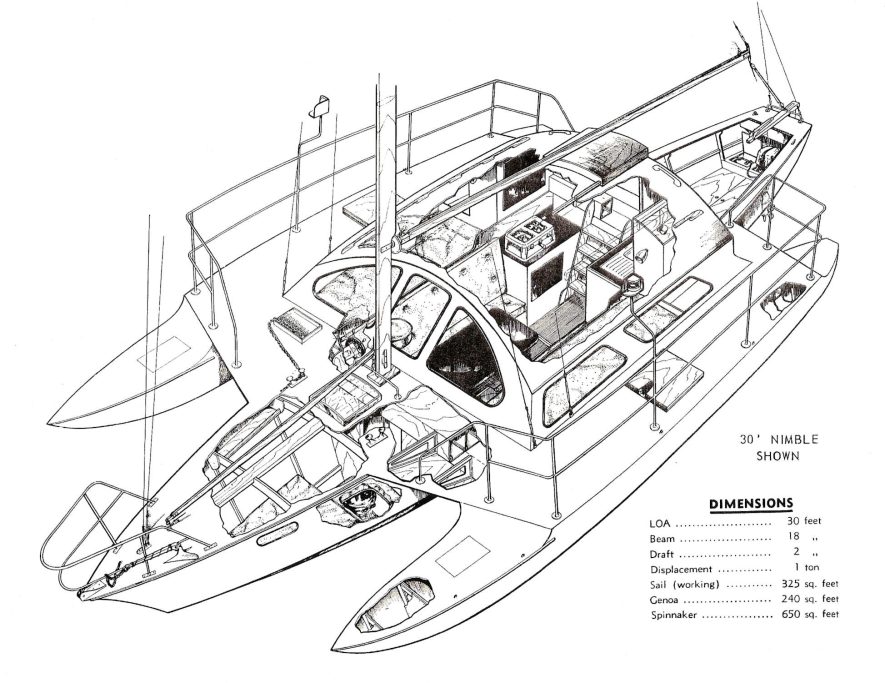

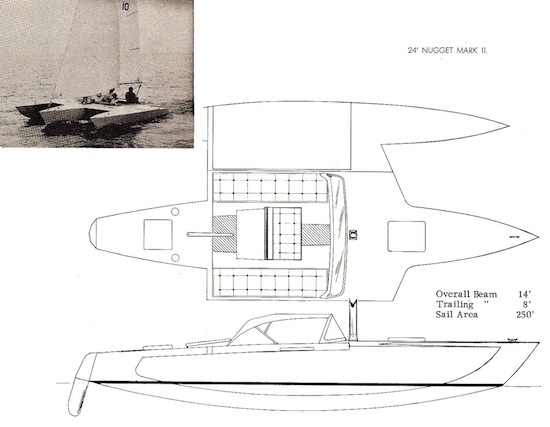

In San Francisco Arthur Piver's experiments led him to start to design easily constructed trimarans for amateur construction. The largest he had produced was a 24-foot trimaran called "Nugget" and the third of these was built by a man called Jim Brown who set off to cruise Mexico in his Nugget. Piver developed this design into a 30-foot demountable trimaran called Nimble built in 1959. Piver and a crew sailed her to the UK in 1960 planning to then race back singlehanded in the first OSTAR promoted in the USA by the Slocum Society. Unfortunately, Piver had to fly home and did not compete in the OSTAR.

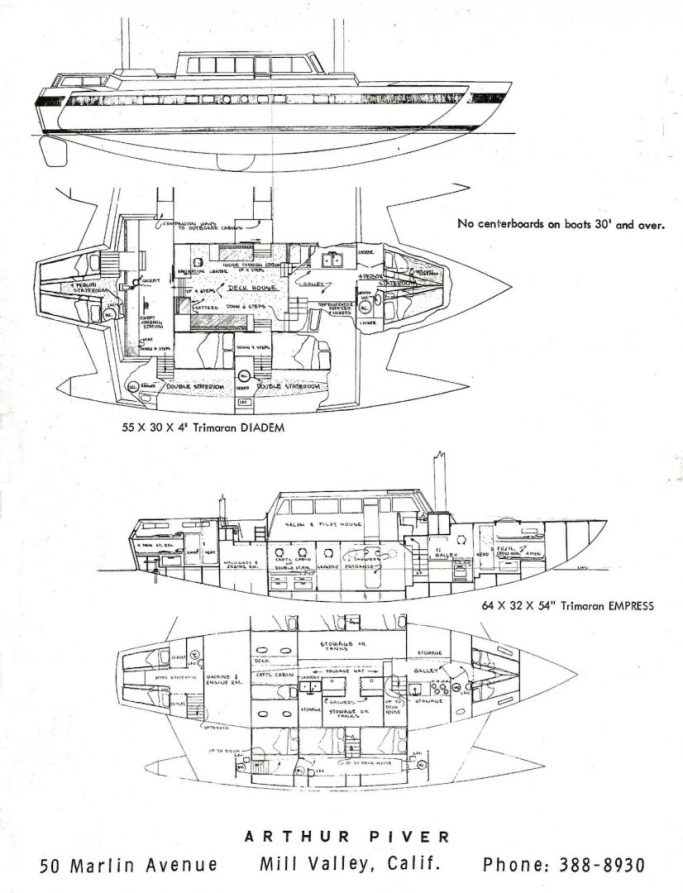

In 1962 Piver sailed a 35-footer called Lodestar from San Francisco to New Zealand. He publicised his voyages by writing books and articles and it has to be said made some pretty outrageous claims about the abilities of his boats and their speed. Professionally built in England by Cox Marine the production Nimble 30 - Lodestar 35 and Victress 40 were strong sellers and were bought by often inexperienced sailors that undertook some long voyages across the Atlantic and even on to Australia and New Zealand. Piver's design business was called Pi- Craft and soon there were many examples being built and sailing trans ocean voyages. There were disasters too because many new trimaran sailors did not appreciate that they could capsize. The stiffness under sail particularly with the massively buoyant outrigger floats preferred by Arthur (who condemned the trend towards low buoyancy outriggers taken by many designers) caught them out. Some designs suffered from overloading because of the vast space in three hulls and the large cabin of the Piver and this caused battering under the decks that caused them to break, and the boats also smashed their large windows and were swamped. However, these difficulties caused by the early pioneering nature of the designs and the defects in the plans meant that the buyers and builders were part of the development work and the learning process. It is said that Piver's voyages broadened the public perception of seaworthiness for the trimaran concept and in a very short time. Piver designs became incredibly popular and inspired many novices to believe they could build their own boats and set off for the tropics. Thus, Arthur Piver could be said to be the man most responsible for popularizing the nautical phenomenon of the cruising multihull partly because he inspired many who built or sailed on his designs to develop them. Jim Brown and Derek Kelsall fall into this category. Nobby Clarke the charismatic sales manager at Cox Marine building Piver trimarans in England certainly believed that he improved on Piver's work too and detailed his adventures and the success of the designs in several books. Piver's career came to a premature end in 1968 when he set out in a borrowed Nugget to do a 500-mile solo qualifying voyage for the 1968 OSTAR. His newest design Stiletto was awaiting him in England but he was never seen again and may well have been run down by a ship, but we will never know. Together with Hedley Nicol the Australian designer of the same period he was lost at sea in one of his own designs.

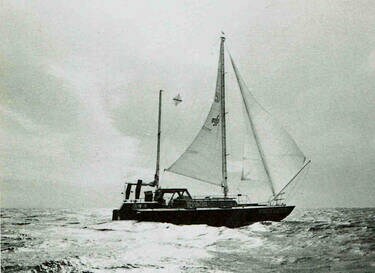

His designs ranged up to a mighty Empress 74-footer to the 24-foot Nugget. Victress was a 40-footer design many of which sailed the Oceans and sailed around the World. A production model named after the class was built in the UK and her owner Nigel Tetley raced her in the 1966 Around Britain Race. He entered her in the 1968 Golden Globe race after failing to obtain sponsorship to build a racer. Victress was home to him and his wife and his two children. He took a photograph of his having Christmas dinner in relative luxury of the trimaran's saloon. Believing he was going to be beaten to the line by Donald Crowhurst in his modified version of Piver’s later 40-foot trimaran. Tetley pushed the overloaded and battered trimaran too hard. The bow of one of the outrigger hulls had already split the plywood skins and broken the inner frames. The bridgedeck between the main hull and the outrigger was disintegrating and eventually broke off flooding the boat and putting a lie to the oft quoted claim of unsinkability Victress was last seen sinking as her skipper hurriedly launched his life raft. Tetley was rescued from his life raft but had crossed his outward track and therefore was really the first man to circumnavigate alone in a multihull rounding three capes including Cape Horn and sailing safely in the Roaring Forties where the pundits said the waves would roll her over and smash her to pieces. It should have been celebrated as a great achievement but was not appreciated because the establishment sensed victory in that the trimaran had broken up rather than win the race. Crowhurst also appeared to have deliberately chosen to end his life rather than admit to his voyage around the World was a fraud. He had sailed around the Atlantic giving false positions by radio and his yacht was found empty. Tetley wrote a book and had Kelsall design and build him a 60-foot trimaran to make another attempt at a non-stop circumnavigation. Apparently struggling financially, he was found hanging from a tree choked by women's underwear. A sad end for a complex and brave man who was above all a fine seaman.

Dick Newick

American Multihull Designer 1926 to 2013

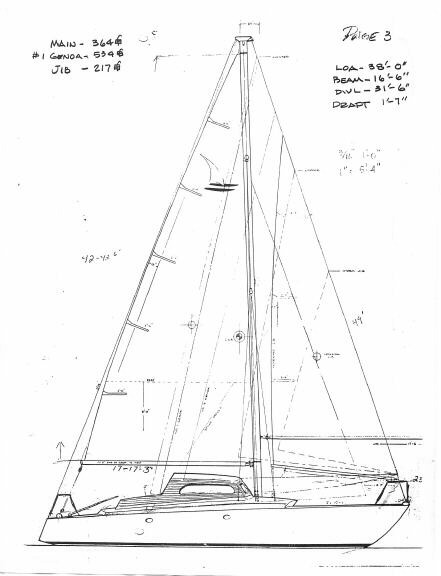

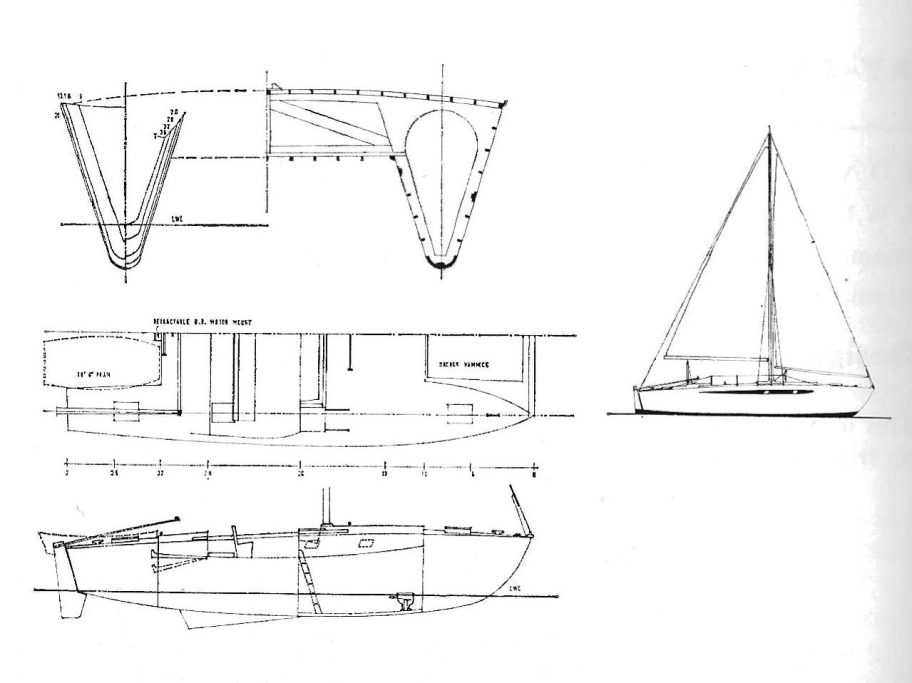

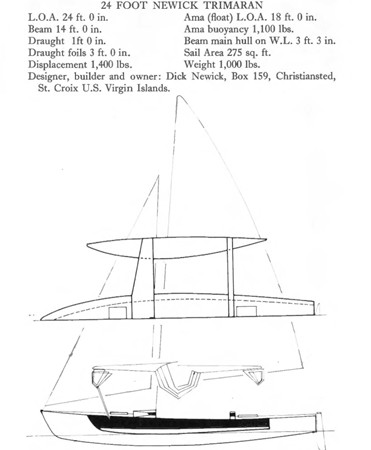

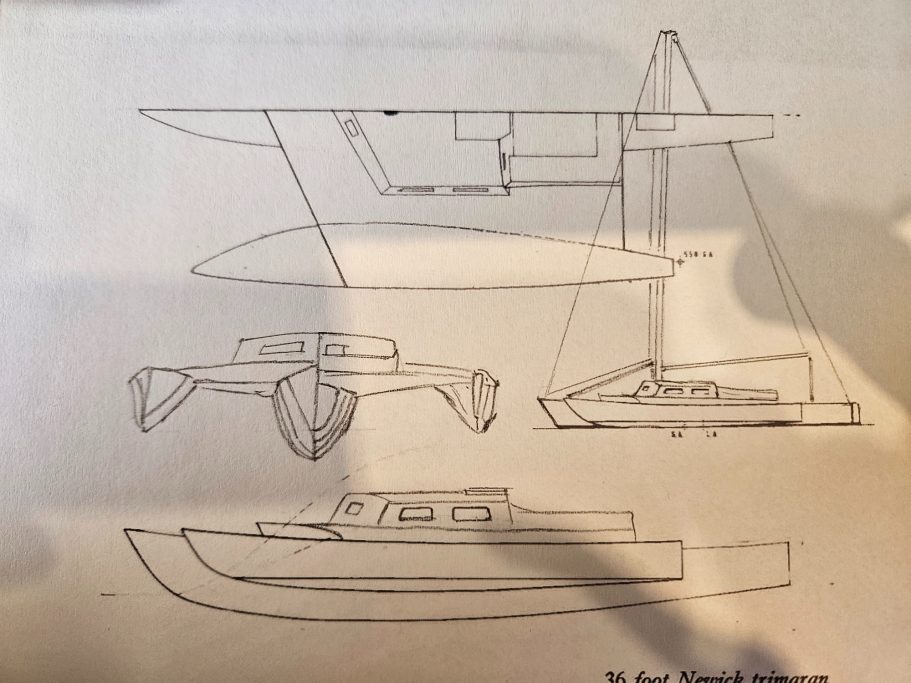

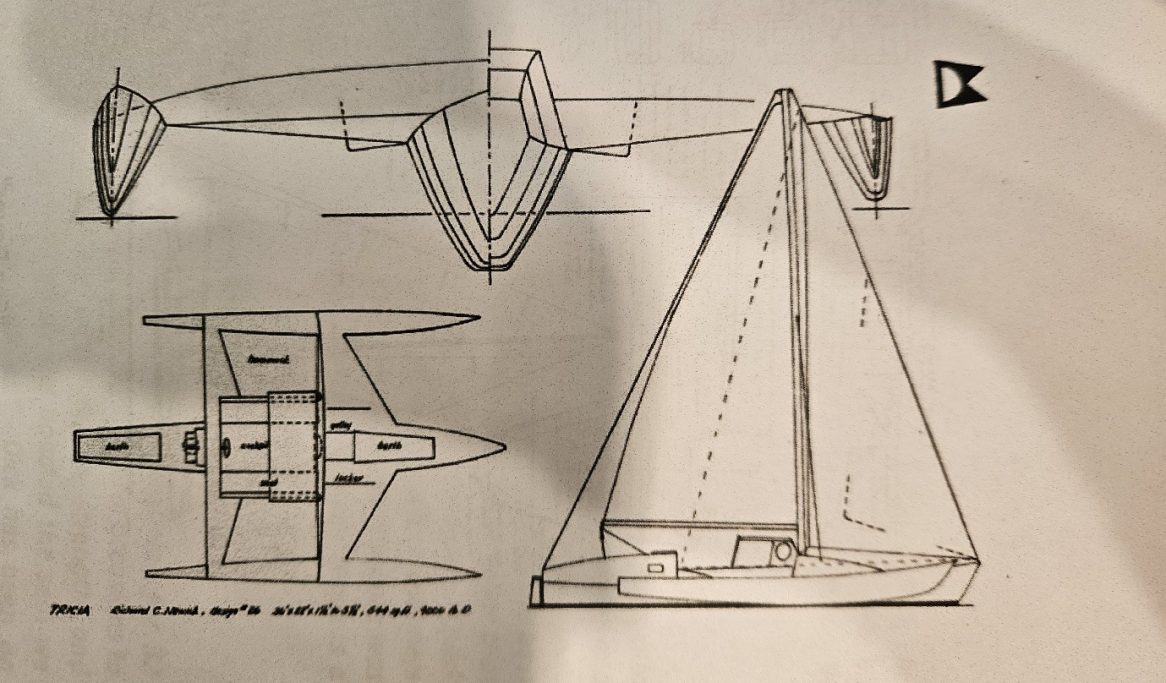

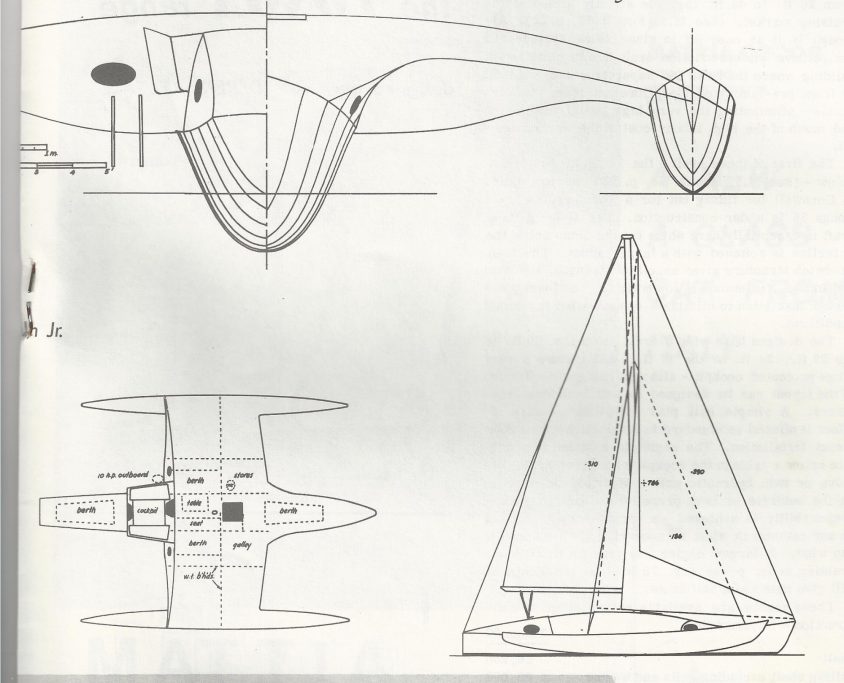

Richard C Newick (known as Dick) is a revered and famous pioneer who emerged in the 1950's with Piver, Choy, Kelsall, Wharram and others and equally left an amazing legacy in his designs and in their achievements that established multihulls as here to stay. Starting as a kayak builder and designer, Dick started his multihull career with a 40 foot catamaran for his day charter tourist business based in the Virgin Islands launched in 1956. However following on from her success he continued to experiment with trimarans for speed. His first in 1960 was another day charter yacht called Trine. She was 32 feet long with relatively short hard V shaped floats (not dissimilar to the original Nimble of Arthur Piver. He designed her with advice from McLear and Harris as consultants. Dick also consulted Erick Manners in the UK and Tchetchet and Louis Macoulliard in the US. In 1962 he designed Lark a 24 foot day sailor again with small submersible floats.

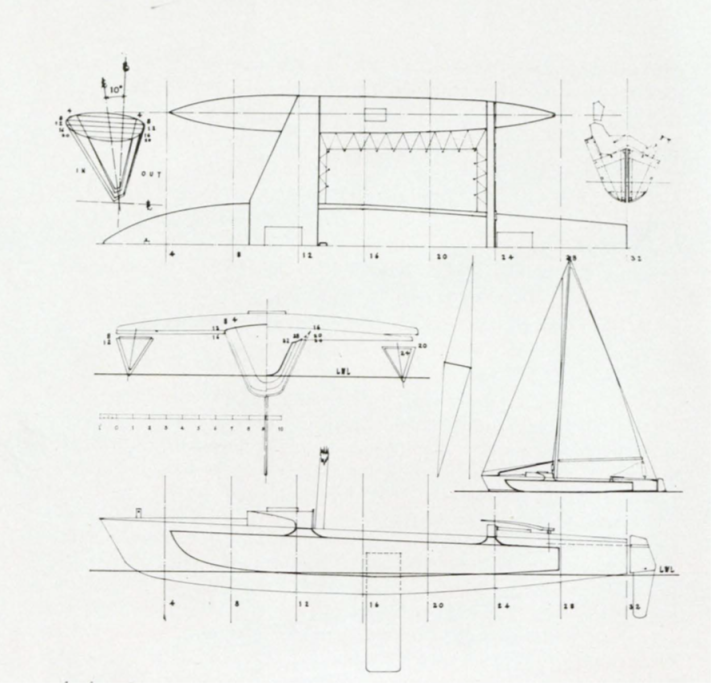

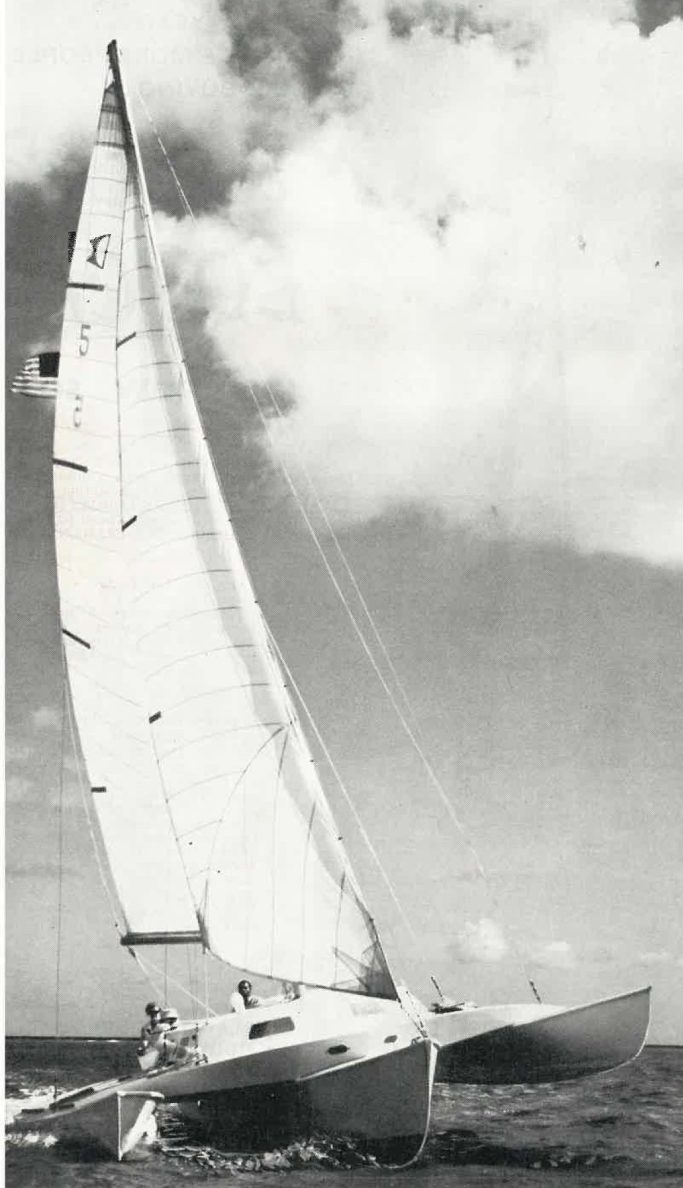

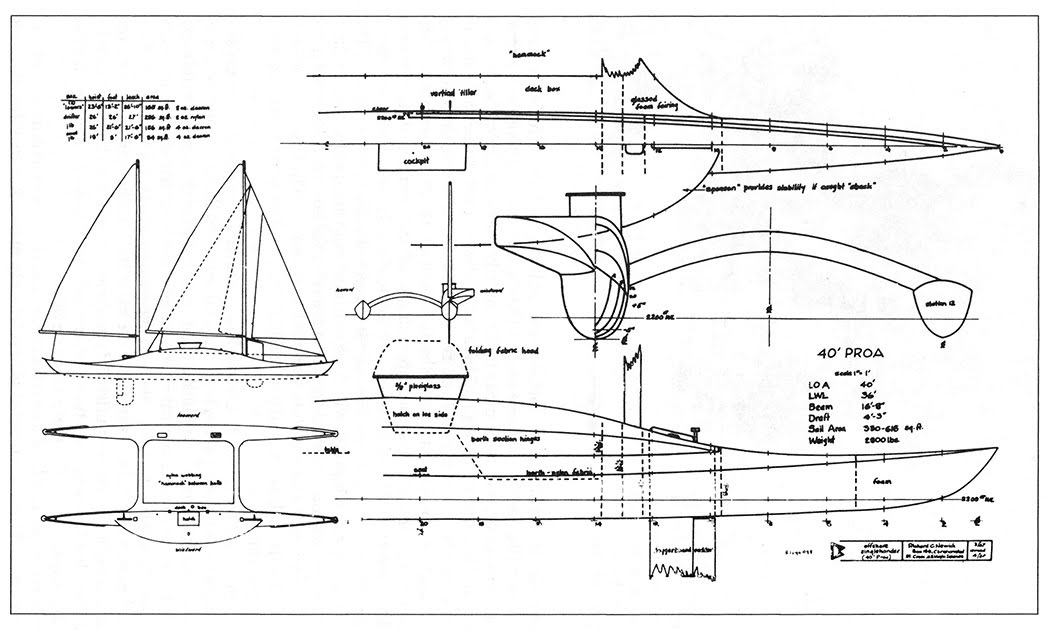

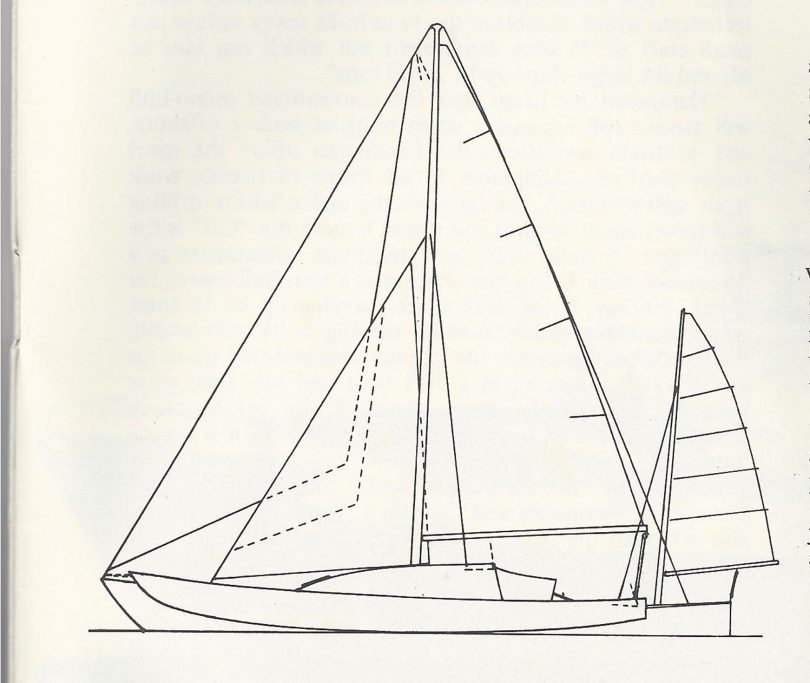

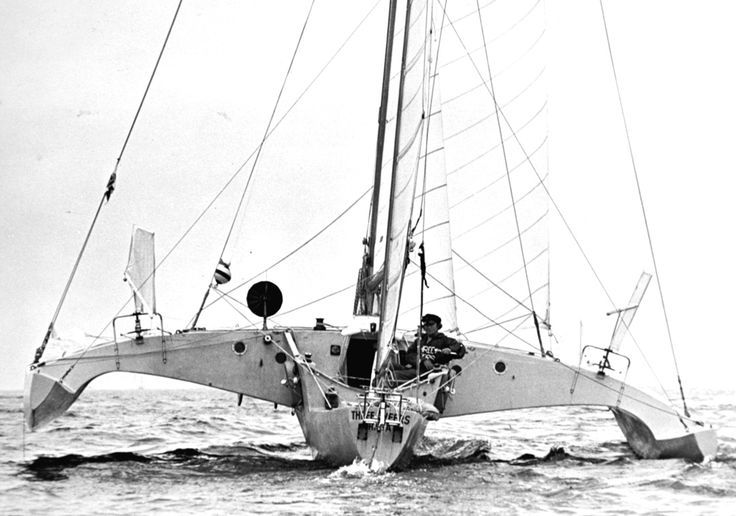

In 1962 He made a giant step forward with his first ocean going trimaran the Trice which was successful and fast with a round bilge main hull and rounded curved V floats. More trimarans followed and in the wealthy enclave of the Virgin Islands he made good connections to finance his designs. He entered the World stage and shocked the establishment in 1967 when he created a proa or single outrigger craft for the 1968 OSTAR. Cheers was craft that carried the outrigger to leeward as a stabiliser. She resembled a catamaran with the rig on the windward hull. Although 40 feet long she had minimal accommodation for her skipper (Newick's long term associate Tom Follett). The stuffy English yacht club who organised the OSTAR initially refused to allow the entry deeming the craft to be extreme and dangerous. Follett finished an amazing third behind two 50 foot mono hulls. One report described overhearing an onlooker at Rhode island saying " He must be nuts to sail that thing".

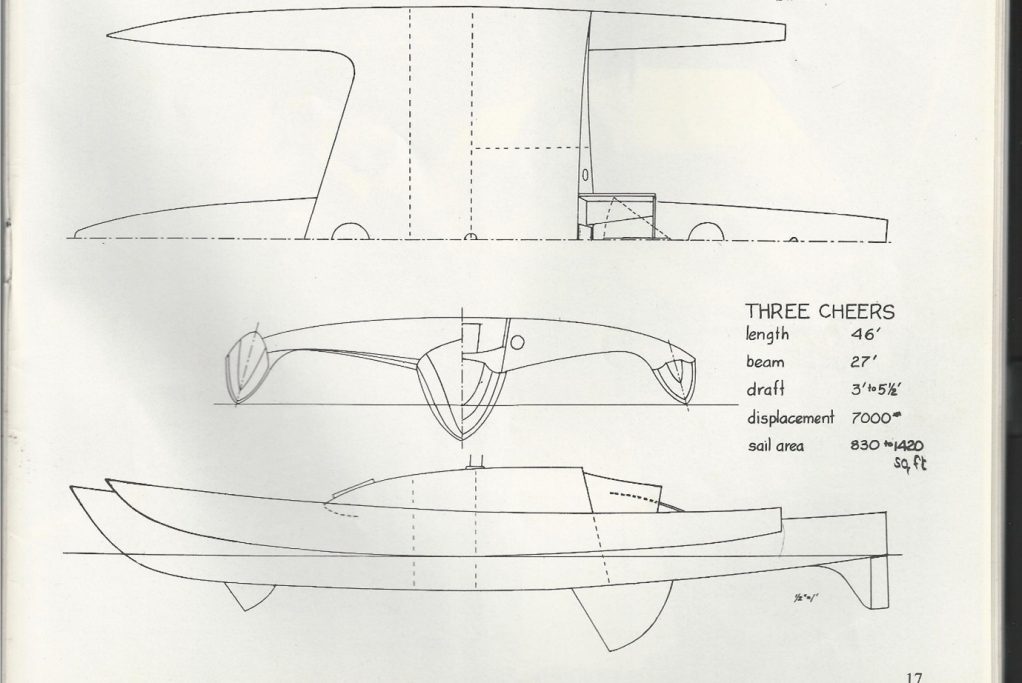

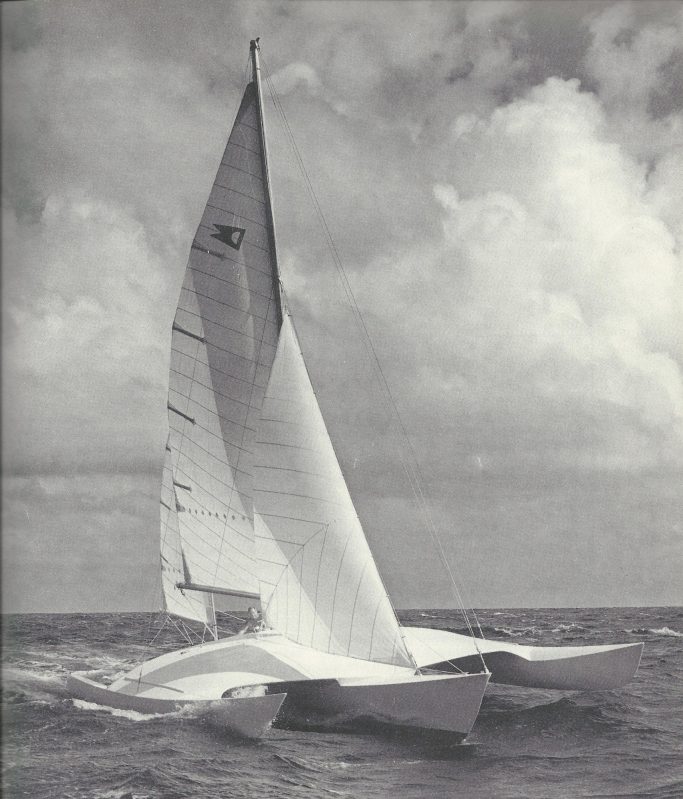

Proas became a long term obsession of Newick although none achieved the success of Cheers. In 1972 however Follett was back and finished fourth in Three Cheers a 46 foot trimaran with a distinctive whaleback deck joining the three hulls. She was a beautiful creation painted bright yellow and finished well but Follett thought he could have won had the boat self steered but she would not because she was so fast that windvane self steering would not work and Newick's ketch rig that was intended to give balance combined with two centreboards failed to deliver balance and self steering. She was the inspiration for a whole new breed of trimaran. In 1976 she had been bought by English yachtsman Mike McMullen. He had fallen in love with her and after sailing her back to the UK on her third transatlantic voyage raced her in the Round Britain race and sailed her extensively. Sadly his wife was killed working on the yacht just before the OSTAR and after the start McMullen was never seen again. Wreckage identified as being parts of Three Cheers was washed up in Scotland later suggesting that the yacht has been smashed to pieces possibly by a collission with a ship. It is likely that thisnis the most common reason for single handers to disappear because necessarily they cannot keep watch while asleep. Today with advanced batteries and equipment like AIS and radar a single hander can set alarms and at least rely on equipment to maintain electronic watch. Mike McMullen had nothing like that and one has to doubt that his mental state after suffering the trauma of Lizzie's death, was best suited to the task he set himself.

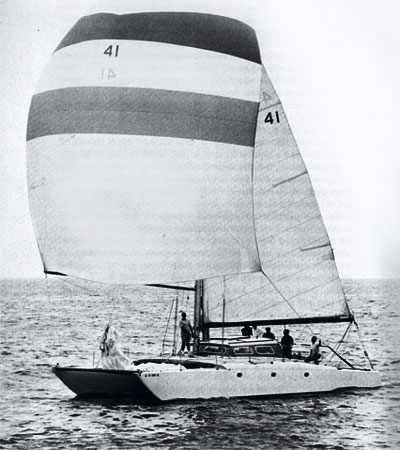

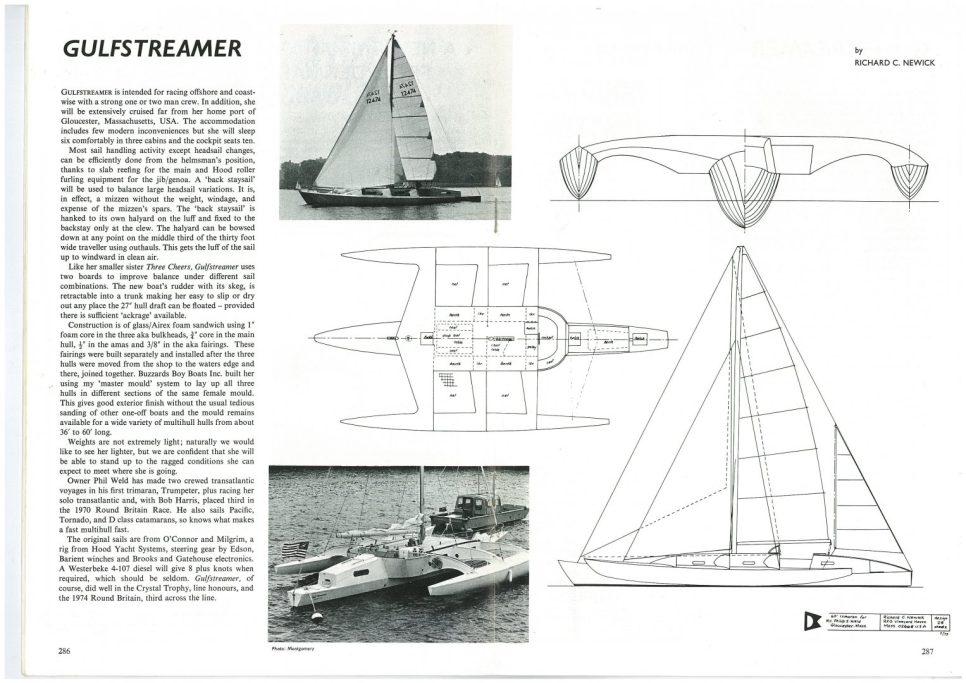

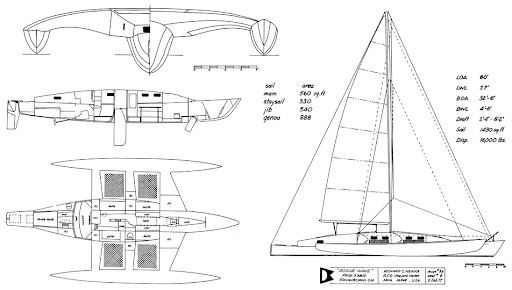

Phil Weld tiring of his Kelsall trimaran Trumpeter turned to Dick Newick for his next boat and Dick drew the 60 foot Gulf Streamer in 1974. Built in foam sandwich she was launched and sailed to Plymouth UK for the Round Britain Race finishing second to Knox Johnston's 70 foot British Oxygen catamaran. Returning to the USA she set out again in 1976 intending to race back in the OSTAR. Disaster struck appropriately in the Gulfstream when in the aftermath of a storm Weld was in his bunk with a crewman on the helm when a massive wave overwhelmed the yacht from behind and she broached and was rolled over by the breaking wave. In effect it seems to have been a cross of a pitchpole as the yacht was lifted onto her nose by the wave and a roll over as she broached and went across diagonally rolling her lee float under. Newick designed low buoyancy floats on his designs that displaced no more that the weight of the yacht so with the added force of the wind in the rig and the overturning moment of a breaking wave the vessel will roll the lee float under and it can trip her up rather than add sufficient righting moment that the yacht stays upright. It may be that the size and force of the wave would have destroyed any yacht but Weld and his crew survived and lived inside the trimaran until rescued. After the rescue Weld flew back trying to find his yacht but failed to locate her. In fact she was picked up by a Russian ship and taken to Odessa and rebuilt to sail on. In 2025 she lies submerged and abandoned in Martinique.

Newick drew Weld an improved version of the same design called Rogue Wave which used similar hull lines but improved cabin and cross arms structures. This time she was built in coldmolded wood epoxy construction by the Gougeon Brothers. This trimaran came to the UK too for the 1978 Round Britain race finishing third to two 50 foot Kelsall trimarans but was deemed too large for the 1980 OSTAR which restricted entry size following the entry of a 128 foot schooner and then Alain Colas' 300 foot monster yacht.

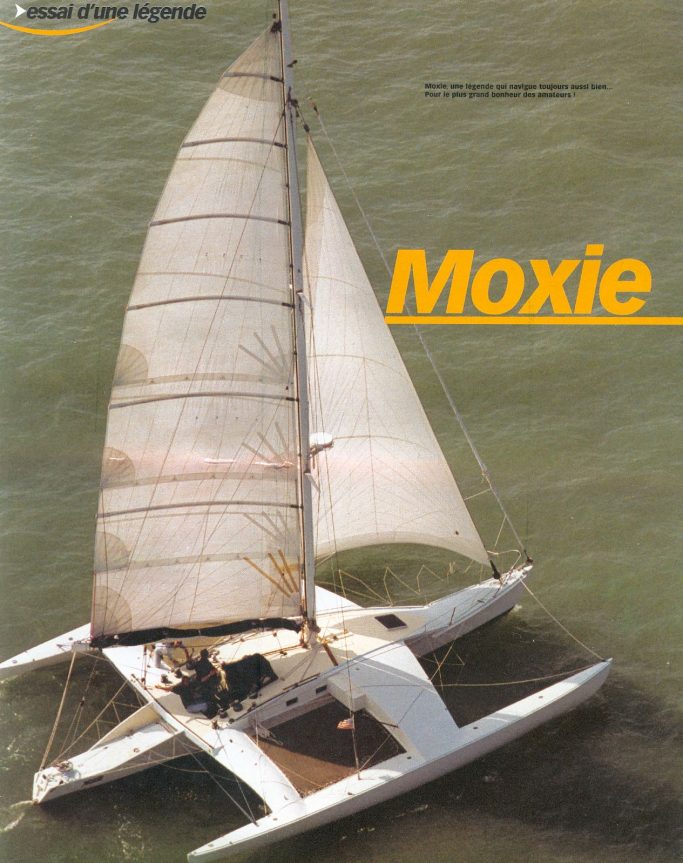

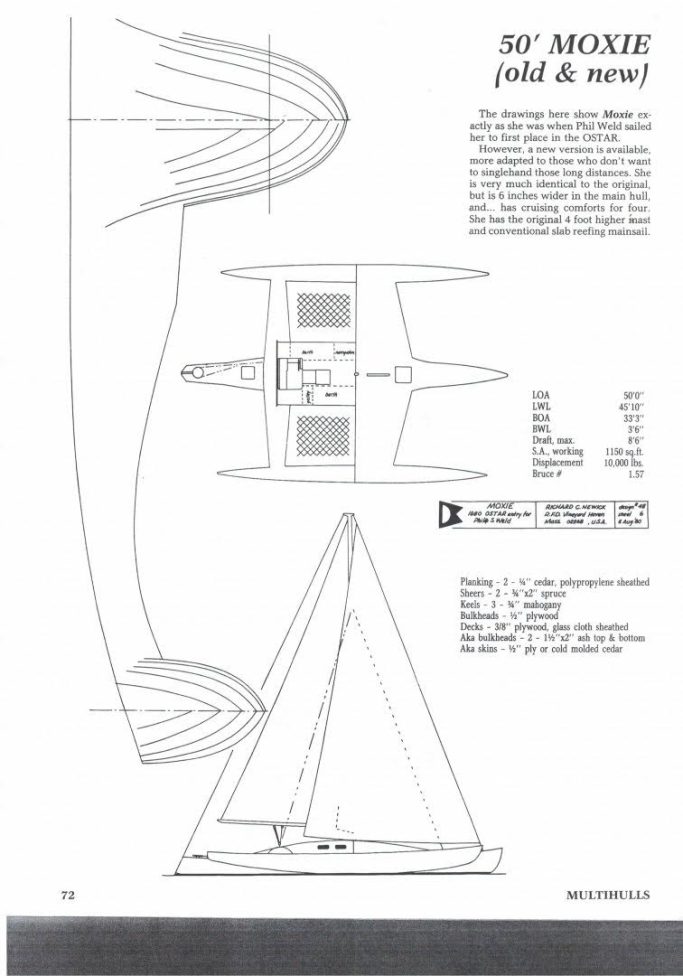

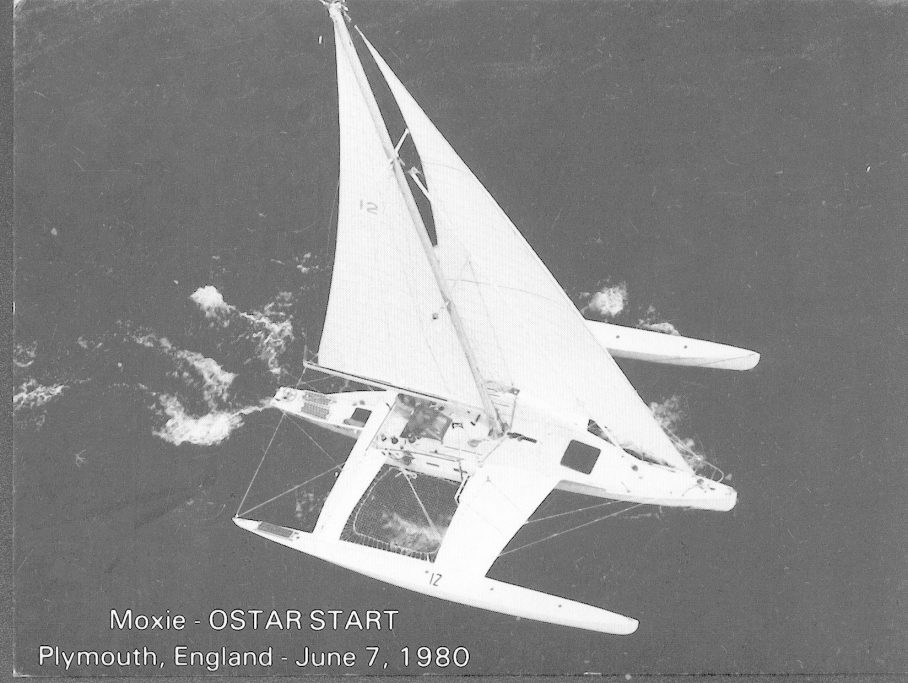

A furious Weld turned to Dick Newick again for an extreme lightweight 50 foot racer called Moxie in which he achieved victory in 1980 pipping Nick Keig in his 53 foot Kelsall Three Legs of Mann III (a luxury cruising yacht) to the post by 7 hours. Mike Birch raced in a 46 foot Three Cheers design called Olympus Photo coming fourth to Moxie after damaging the underside of the bridge deck which he stopped racing to repair and stop the ingress of water. It added to his delay that he was trying to decide whether the repaired boat was safe to race on before deciding to continue.

Interestingly Nick Keig had suffered damage to his mainsail that slowed him down and Eugene Riguel was well down the field in VSD another 53 foot Kelsall with a broken dagger board and damaged sails.

The first five boats home were all trimarans and all arrived within 20 hours. Just as Weld had found on Trumpeter in 1972 when that very fast trimaran also limped in with damage well down the field too having a fast boat was essential but a lack of gear failure and good luck were too. In Moxie the 65 year old Weld had delivered a perfect race in a trimaran that was possibly Newick's greatest design.

Dick Newick's fame was also boosted in the 70's when he had designed a boat sometimes called a transatlantic daysailer, the semi production Val 31. In 1976 three of these entered the OSTAR and Mike Birch came second to a 73 foot mono hull sailed by French star Eric Tabarly. In 1978 Birch won the French Route de Rhum race in Olympus Photo a 33 foot Newick/Greene trimaran before building the Three Cheers design of the same name for 1980.

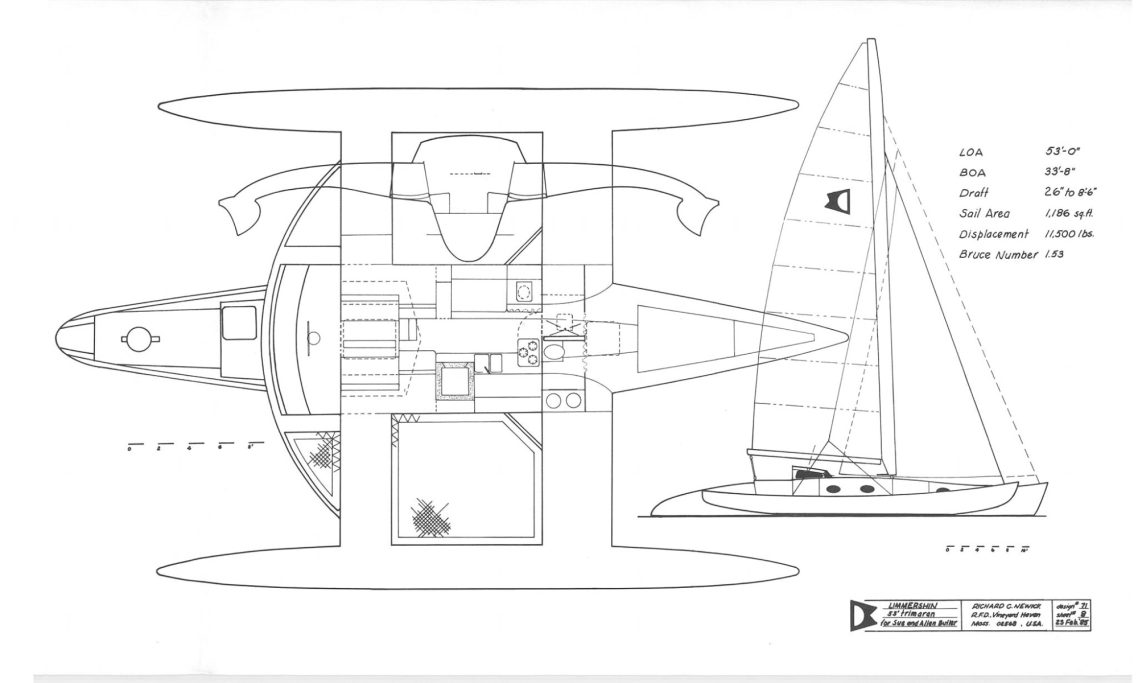

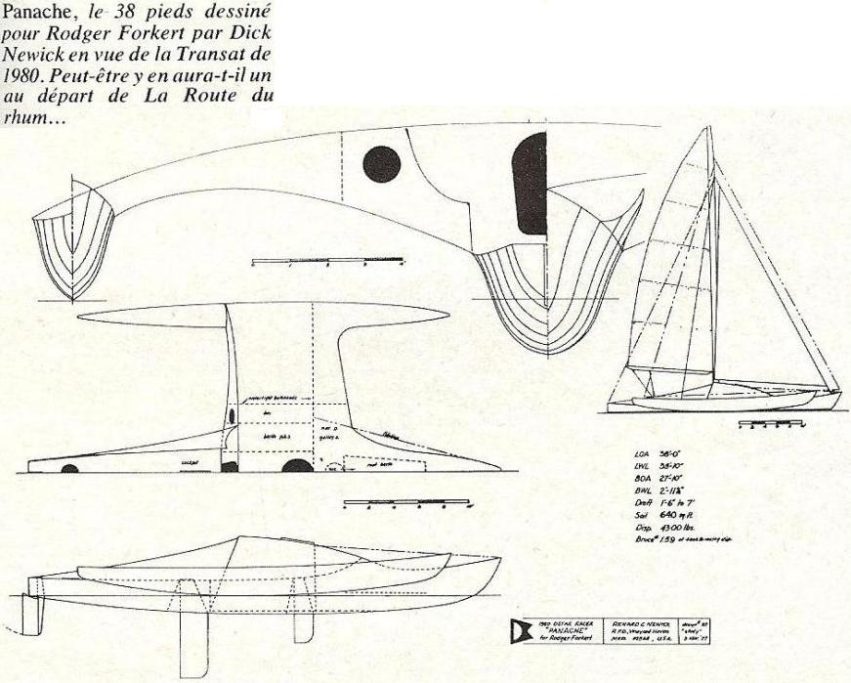

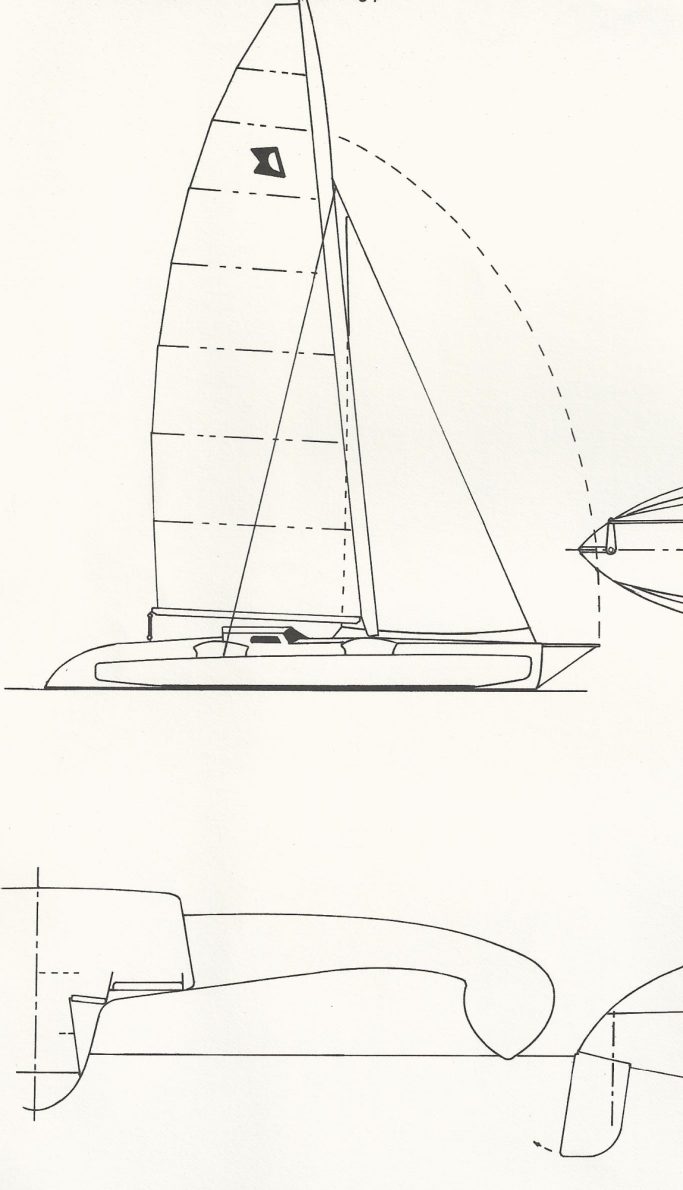

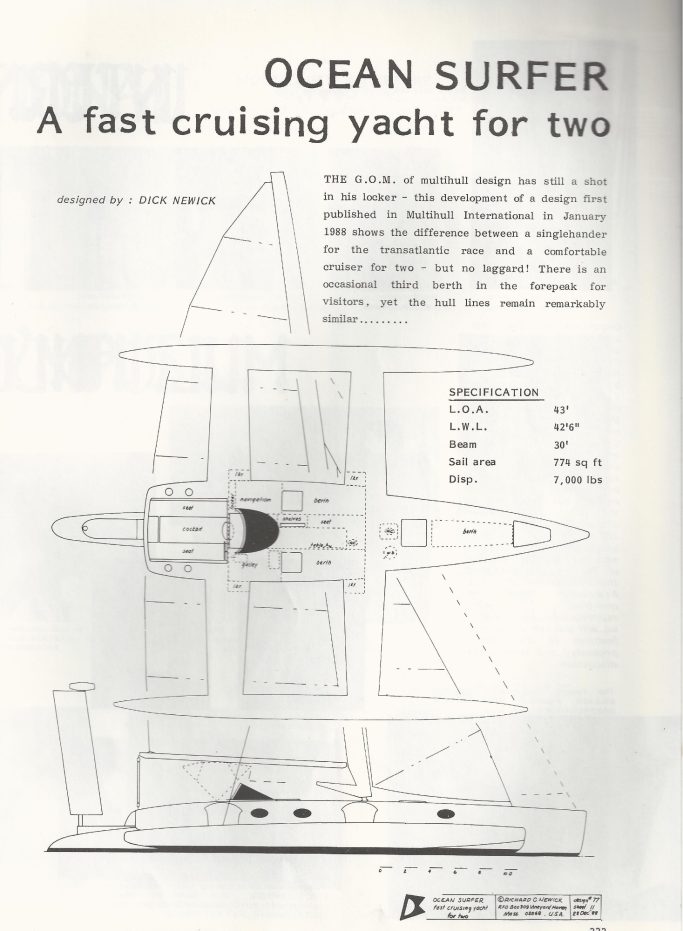

Dick Newick designed many multihulls and his designs still sail today. Most were very light with spartan accommodation and no concession to luxury. He famously said he would not allow the client's wife to design the boat! He also said he could design speed comfort and low cost but never all those characteristics in the same boat. The evolution of designs was fascinating with the shapes evolving as he moved toward long higher buoyancy outriggers. He designed some very popular classes of boat -the Val went through many gestations -a Val 2 and Val 3. In the 36 to 40 foot bracket his Native, Panache, Creative and Echo all developed the same size trimaran concept on similar but evolved lines. His Ocean Surfer design for example was a very different design altogether to his earlier boats. Likewise pat's the yacht he designed for his wife and he to cruise but they never did because by the time he had finished the build Pat was no longer willing to suffer the deprivation of home comforts required to cruise a Newick.

Moving from the Virgin Islands to Maine he was a full time multihull designer and builder and sailor. He changed his mind on many things and after the capsize of Gulfstreamer he experimented with sea anchors and drogues and techniques to best handle his multihulls in adverse weather. Later when a Val 2 capsized in the Gulfstream in Winter he concluded that it simply should not have been there which was a sensible assessment that while he could design fast exciting boats a lightweight trimaran can never be a boat that is impregnable to the worst the Ocean has to throw at it.

What he did create were yachts that were works of art, light, simple and fast. All of them were unmistakably a Newick.

Lock Crowther

Australian Multihull Pioneer 1940-1993

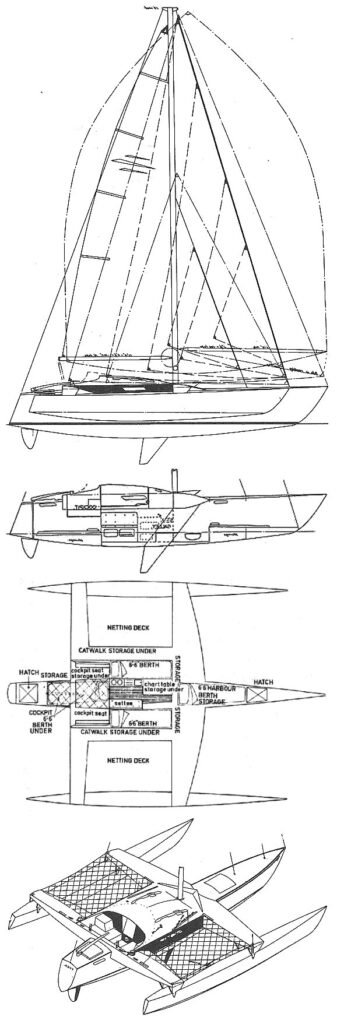

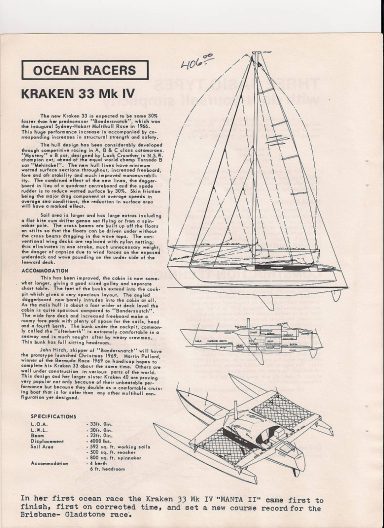

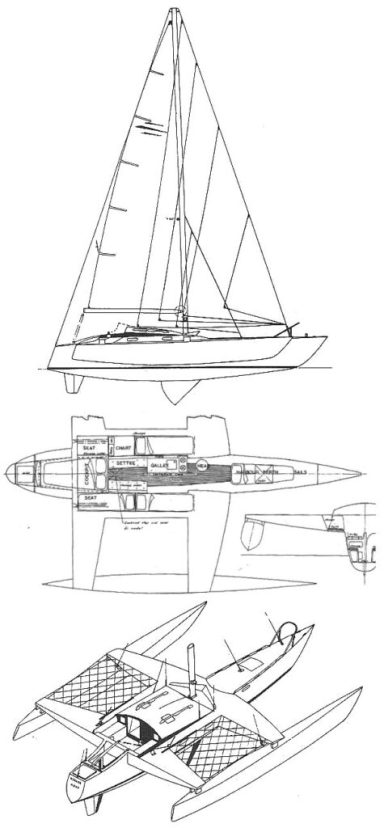

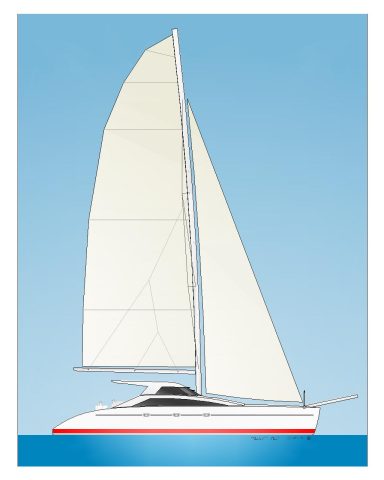

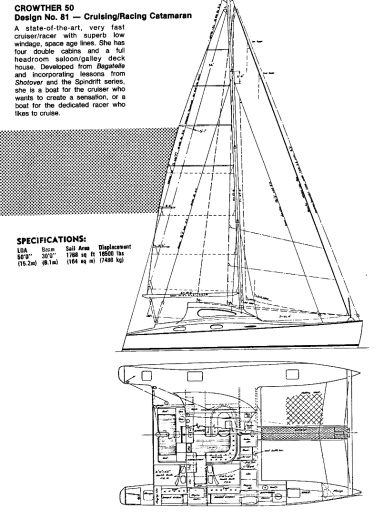

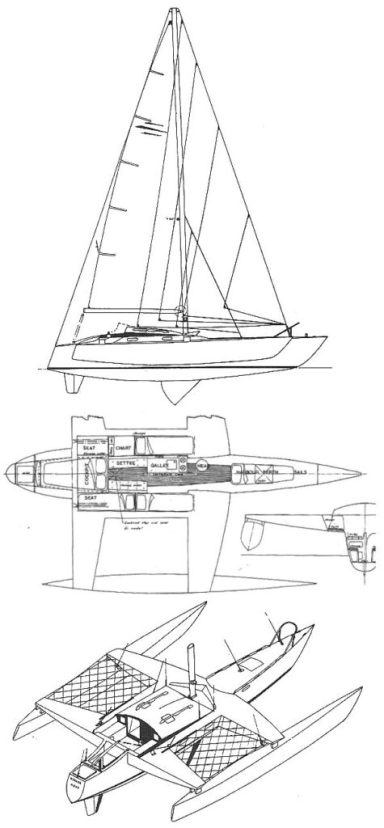

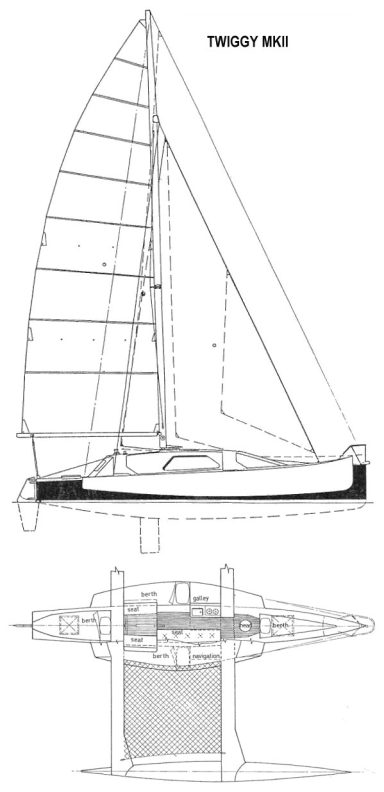

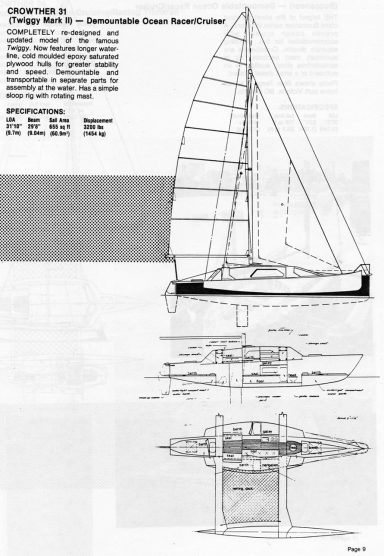

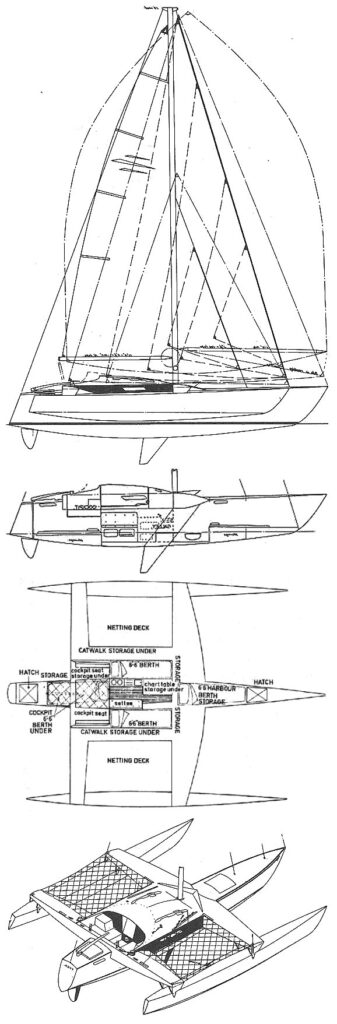

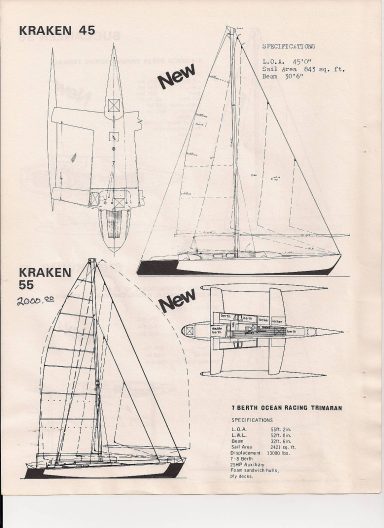

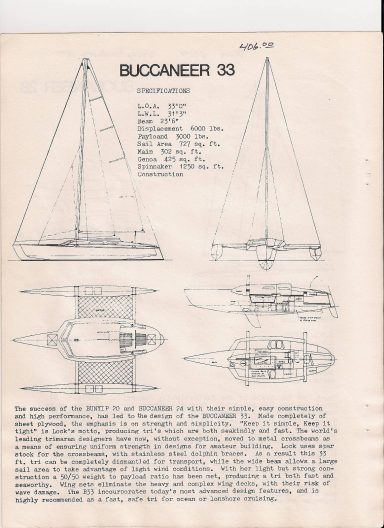

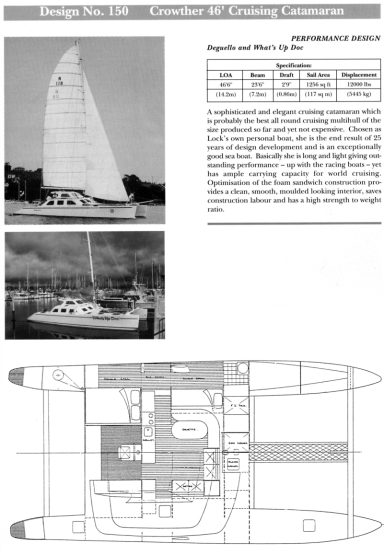

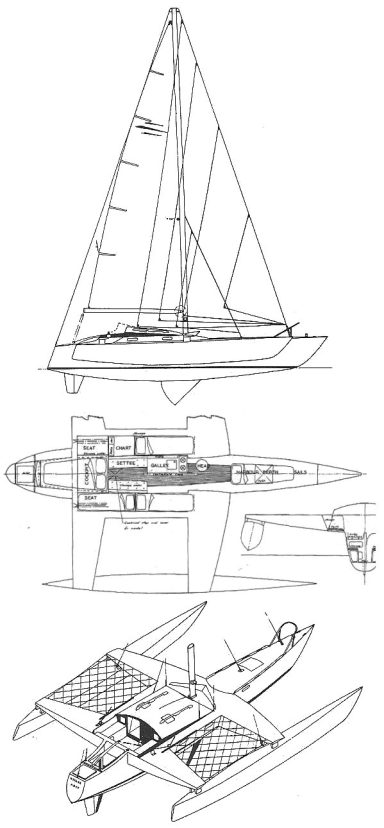

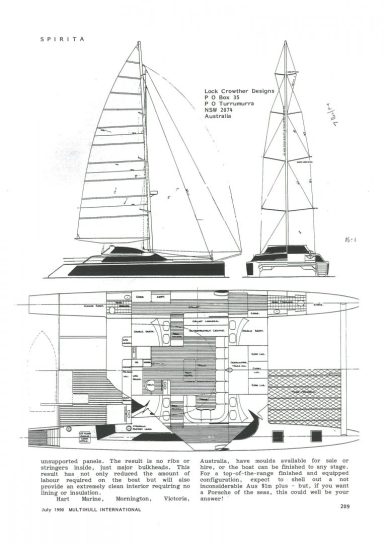

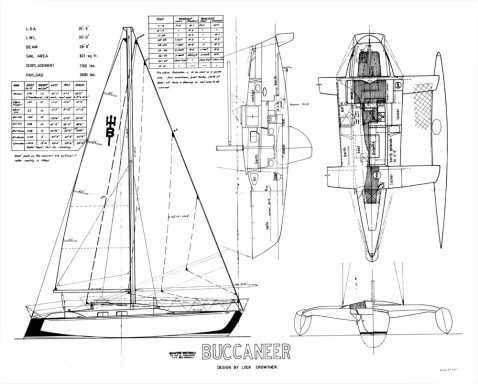

Lachlan (aka Lock) Crowther designed and built his first trimaran day sailor in 1959 -he was a teenager Some of his friends and family wanted to have similar boats and so his design career started. He studied electrical engineering while sailing, designing and building boats as a hobby. In 1962 his Kraken 25 was a very fast racer. His reputation was established internationally in 1966, when his first offshore racing trimaran BRANDERSNATCH won the Sydney to Hobart multihull race. This evolved into the 1968 Kraken 33 class. In 1969, a Kraken 40 won the New York to Bermuda race with him aboard. He quit his engineering career to design full time starting a design business which produced over 2500 boats.

©Copyright. Trilogy Sailing Ltd and Lawrite Limited and Martin Phillips . All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.