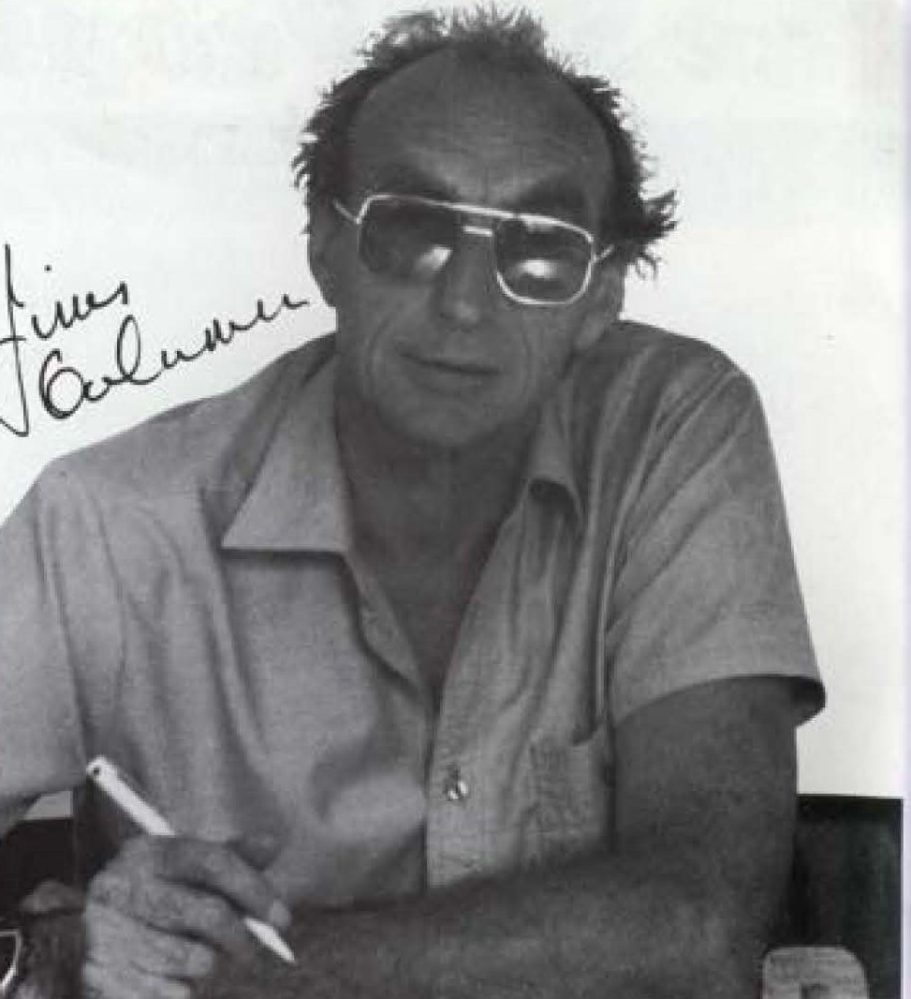

James Wharram

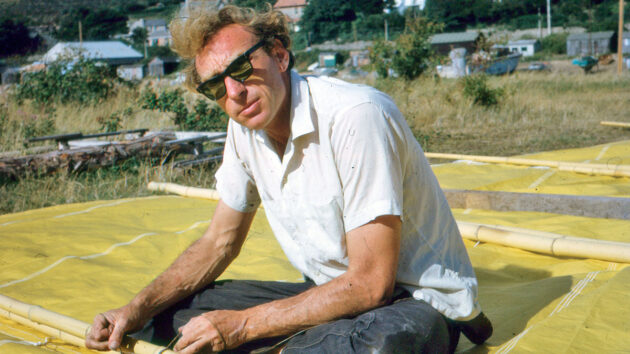

British Catamaran Pioneer 1928 to 2021

James Wharram (aka Jim and Jimmy) was a fascinating character and his story well worth telling.

He is sometimes described as "the father of the modern multihull" but this is not correct because many people were developing multihulls all around the World in the 1950's and early 60's. This development of multihulls all over the World created the modern multihulls that are so popular today, and not the adventures of James Wharram. He was an early pioneer and created a cult around his designs that remains popular with thousands of followers today as an alternative to most multihulls.

It was in the period 1954 to 1961 that James was made his pioneering Ocean voyages in his self designed and built catamarans Tangaroa and Rongo. James later achieved great success with his designs but they are not at all similar to the majority of multihull designs that now dominate the market. Few designers followed the path taken by James, indeed the vast majority of catamarans sold today are exactly the craft that James criticised all his life and you only need to read his 1994 article Nomads of the Wind to see that.

The Wharram website at https://www.wharram.com/articles/how-we-design has a range of interesting articles brilliantly illustrating the Wharram design philosophy. In one called "Thoughts on Multihull design" is a typically prickly response in 2017 to Multihulls Quarterly which had in James' opinion defamed his designs! James delivered a broardside against the modern catamarans featured in the magazine!

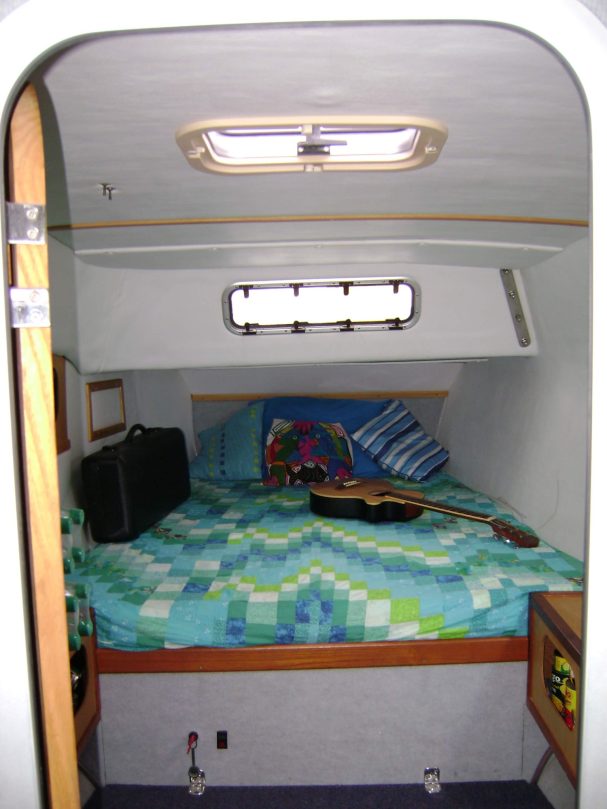

" They are catering for the large charter market, where cabin luxury is put well before seaworthiness. The expansive cockpits and large salons with all-round large windows are great in harbor, but in a serious ocean gale they are the last thing you want. Many now have double berths with a walk-space all round (like in a hotel room), great for the not-so-agile city dwelling owners when the boat is in harbor, but in large seas these berths are totally unsuitable. Though it is perhaps good that multihulls are being more generally accepted, those people who want to do serious blue water cruising should be careful in the choice of boat they make."

Nomads of the Wind was a very romantically inspirational article that set out a wonderful picture of the 64 foot voyaging double canoe Spririt of Gaia as a fantastically seaworthy ship and the free and happy lifestyle of her crew wandering the Ocean just as the ancient Polynesians voyaged to their Islands in the Pacific.

But James' basic premise of the superiority of the Wharram design concept over that of other multihull designers' boats does not stand up to objective examination. It was the constant theme of James's articles and his sales material throughout his life that his design principles produced a more seaworthy, safer and capable vessel than the Western World concepts of "yacht catamarans" .

Today the majority of modern multihull yachts are sailing well in safety and comfort. Some designs are praised for their speed and sailing qualities. They now dominate the World charter market and are an equally popular choice for people going ocean cruising and many of the same catamarans that feature in charter work are also good blue water cruisers as evidenced by reading the reports of the ARC for example will show you. There are a multitude of published written accounts and video accounts of people sailing across the oceans and weathering storms in their catamarans designed with all the features that James derided as unsafe or unseaworthy.

In the 70 years since James designed his first catamaran millions of sea miles have been sailed by modern multihulls and thousands of sailors built a vast amount of multihull sailing experience crusing and racing in seas around the World.

I am not of course suggesting that there are not good and bad catamaran designs, simply that contrary to the opinions espoused by James, a design that clasified as a "yacht catamaran" with a comfortable saloon and windows and roomy cabins and ensuites is a great safe blue water vehicle.

A great example is seen on the You Tube channel of La Vagabonde an Outremer 45 (albeit that they now have a superb Rapido 60 trimaran). The film where they sailed across the Atlantic with Greta Thornberg the Green activist illustrates what I am saying very well.

Of course new catamarans and trimarans are very expensive boats. So are new yachts of any kind. But there are many used examples that make perfectly seaworthy purchases and are not that expensive compared with the cost of building or having built a new Tiki 38 or 46.

So if you agree with James' opinions and believe a Wharram catamaran is more safe or seaworthy that is going to be a personal value judgement or choice. His boats are very different and encompass an entirely alternative approach to the multoihull concept that is also a minority one. But as in all designs there have to be compromises. The choice to sail a Wharram design will be made on many different criteria but the evidence that they necessarily achieve superior structural integrity, sail better or are safer or more comfortable than other "yacht" designs is not supported by the objective evidence. What will attract you will be simplicity, a belief that the use of sustainable wood to build them is better ethically than buying a grp boat or simply that their shapes and style that are so different are more attractive to you.

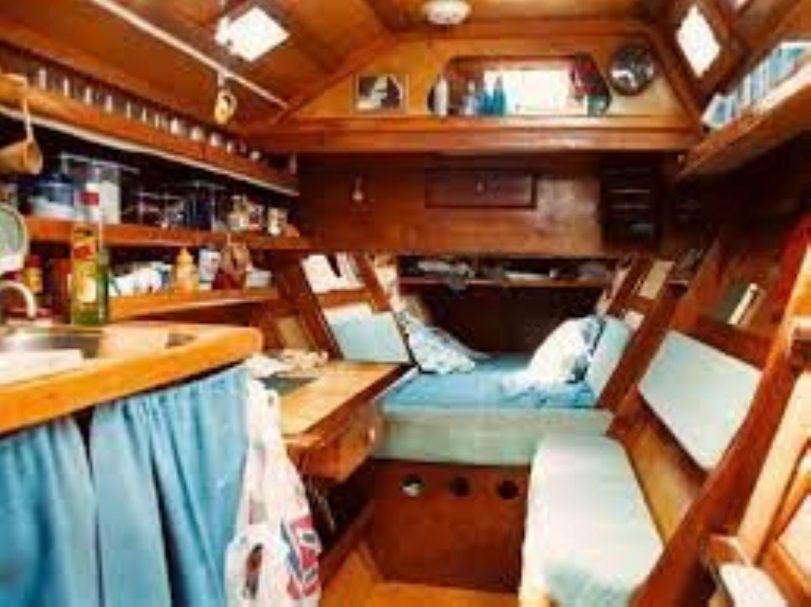

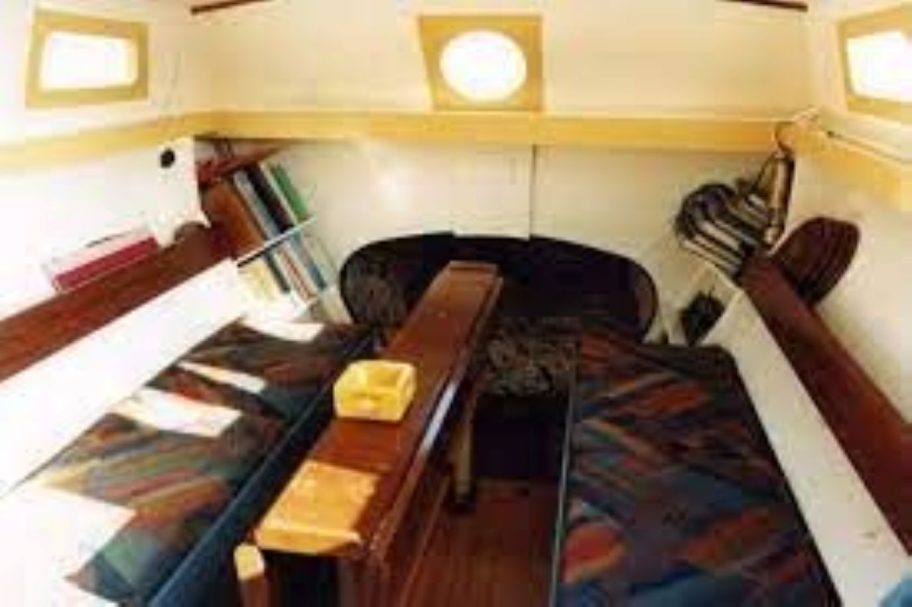

I think Spirit of Gaia is a beautiful boat and one I would love to sail on and I have always admired the Pahi range of boats. I coloured in the study plans of the Pahi 42 and had them pinned on the wall in my study many years ago, as my dream ship project for building to sail away from the "rat race" one day. Wharram catamarans have a great attraction for me as they have for many others. Many well built Wharram designs are really good boats in a very different way to most catamarans. The Wharram wingsail rig is a very alternative and effective rig that is the opposite of common yacht rigs and a sensible cruising choice. And everything about Wharram catamarans is based on a keep it simple approach. There are many films of sailing on Wharram catamarans particularly patching up old wooden examples (see Women and the Wind). However what does shine through some of them to me now is the discomfort of an open decked craft and the dark and damp cabins.

So to credit James with the creation of modern multihulls as some writers have is not accurate at all. He spent his entire life fighting against modern multihulls and their designers arguing the case that his designs were better. He suceeded in creating a huge following of people attracted to alternative solutions and a mythology around himself and the qualities of his boats which can however be subjected to objective fact checking.

What James did achieve for the progress of multihulls as a whole was to sail a catamaran across the Atlantic from East to West on the now, well trodden path via the Canaries to the West Indies and then to sail from New York to Ireland achieving a West to East crossing of the stormy North Atlantic proving without doubt that the multihull concept was seaworthy at a time when conventional thinking was that they were unsafe.

However unfortunately these fantastic achievements were largely ignored by the sailing community for decades even after he started selling plans for self-build catamarans in the late sixties.

In the late 70's and since James gained a wide recognition for his designs and voyages; but he was equally recognised because of his unconventional lifestyle, and outspoken opinions as for the particular qualities of his designs. What was making headlines in the late fifties and early sixties was the achievements of Arthur Piver and Rudy Choy and of course in 1964 and 1966 the success of Derek Kelsall in the OSTAR and RBR; production boats from the Prouts, Bill O'Brian, Sailcraft, and Pat Patterson made a big impact in the market in the 1960's and 70's and many multihulls were designed and sold for racing and cruising.

While this was going on James frequently expressed his view that the modern consumer society was doomed and that governments would destroy the Planet. His basic (and not particularly original or sophisticated) philosophy was that people could escape the "rat race" of life on land and live on a boat forming sea communities fitted into the whole self-sufficiency movement of the 70's. He quoted French maverick sailor Bernard Moitessier's saying that there were "land bastards" and "sea people".

James was still preaching the same story together with the pleasures of free love, multiple relationships, sexual freedom and nudity throughout the 60's and 70's and beyond into the 21st century. Tom Cunliffe (actually a friend of James') wrote a piece in a magazine about him under the head line "Crackpot or Philosopher" which probably sums up different reactions he provoked.

In 1996 a reader asked Charles Chiodi editor of Multihulls Magazine why he did not publish more about Wharram and responded: "I believe the reason why some of the news media is ignoring him .. maybe his unusual lifestyle which I am not going to describe here.

Why they don't publicise his designs is because they think it doesn't fit the description of 'yacht' ". He likened Wharram to Arthur Piver who "..was quite vocal and proud of himself ...(and is dead...). "Wharram is quite vocal and proud of himself- and alive. His principle is similar to Piver's ; design a simple multihull that can be built easily with few tools and little practice. Then go sailing".. He went on to say that a Wharram catamaran "...as a status symbol is near the bottom of the pile..".

Inadvertantly Chiodi defined the attaction of Wharram designs perfectly when he said that because I doubt if anyone ever bought or built a Wharram catamaran because they cared remotely about whether their boat was viewed by others as a "status symbol".

To Chiodi it was an intentional insult but while Wharram builders and owners may well care about the workmanship and quality of their boat and its seaworthiness the question of their status is unlikely to enter their thoughts. These are the people that James saw as his type of people. I hope that if James read that comment he was able to have a good laugh while thinking of the thousands of folk that bought his designs and their achievements and lives! Spending years building a Wharram in your back yard and sailing it half way around the World as Heather and Tim Whelan did; or sailing a Tiki 21 around the World like Rory McDougall is a classic example of people who would not care anything about status symbols!

James called himself a philosopher designer. The philosophy was enabled by his low cost easy to build catamarans so he said anyone minded to do so could build an catamaran and sail to "freedom" rejecting the normal life of Western Society.

A wit once wrote that instead of winches, James just had "wenches" on his boats and people that met him of Spirit of Gaia in the 90's and since referred to him and his wenches and their uninhibited behaviour. One guy posted in an online forum discussion about Wharram Catamarans of James telling him about his "latest" girlfriend when they met him on his catamaran Spirit of Gaia in the late 90's (James would have been in his 70's by then).

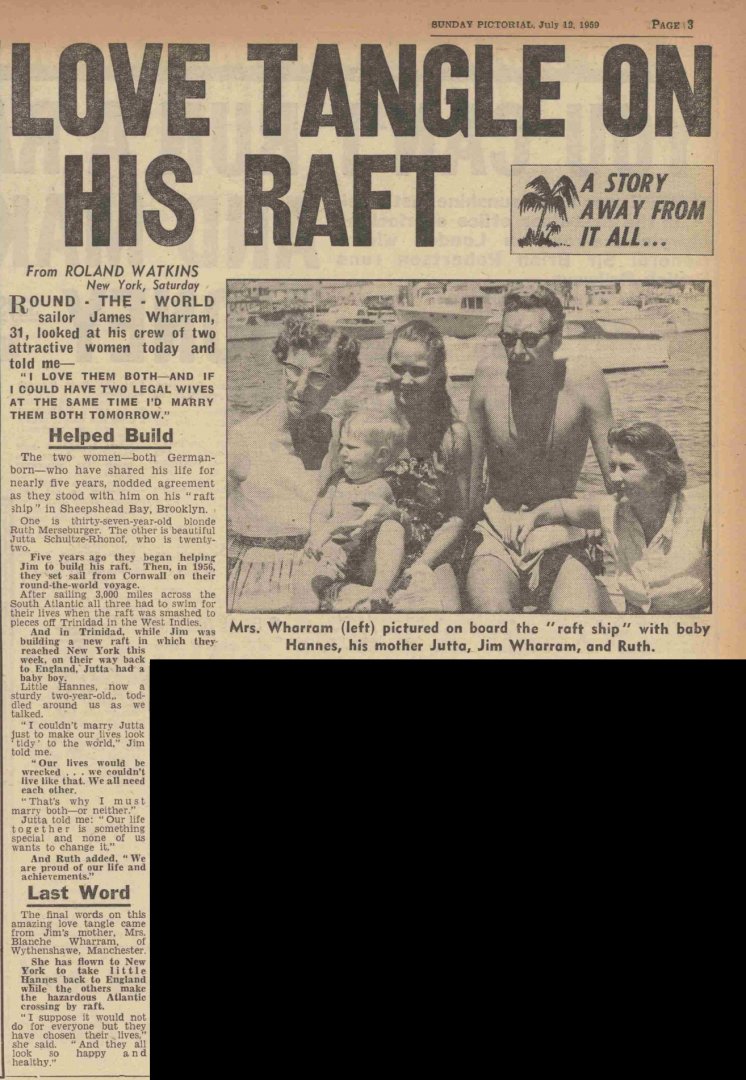

When he first published a book it was a now long forgotten work with an obscure publisher of naturist books and magazines featuring naked photo's of the girls and James. Jutta's naked picture on the dust jacket of his 1969 book "Two Girls, Two catamarans" made it something of a "top shelf" publication as well. I borrowed it from my local library as a young lad and they handed it over in a brown paper bag. I removed the dust jacket and hid it while I read the book so my strictly conventional parents did not see it!

A reviewer in a mainstream UK yachting magazine Motor Boat and Yachting" disliked the book, acknowledging the sailing achievement but not James' "crude" prose likening the ballooning sails to a woman's breasts. They considered it ruined by the "chip on his shoulder" - remember this was in 1969. If that reviewer read James' 2020 autobiography "People of the Sea" they would probably think that "chip" was alive and well on his shoulder fifty years on.

Editing and self publishing his magazine Sea People in the 1980's he even introduced a Nudist/Naturists column with a full frontal nude picture of one of his female friends and wrote about his nudist holidays in Europe. Apart from nudity he preached Green politics, was involved with interlocking (swimming) with dolphins and the self sufficiency movement as well as designing basic boats based on his interpretation of historic Polynesian canoes.

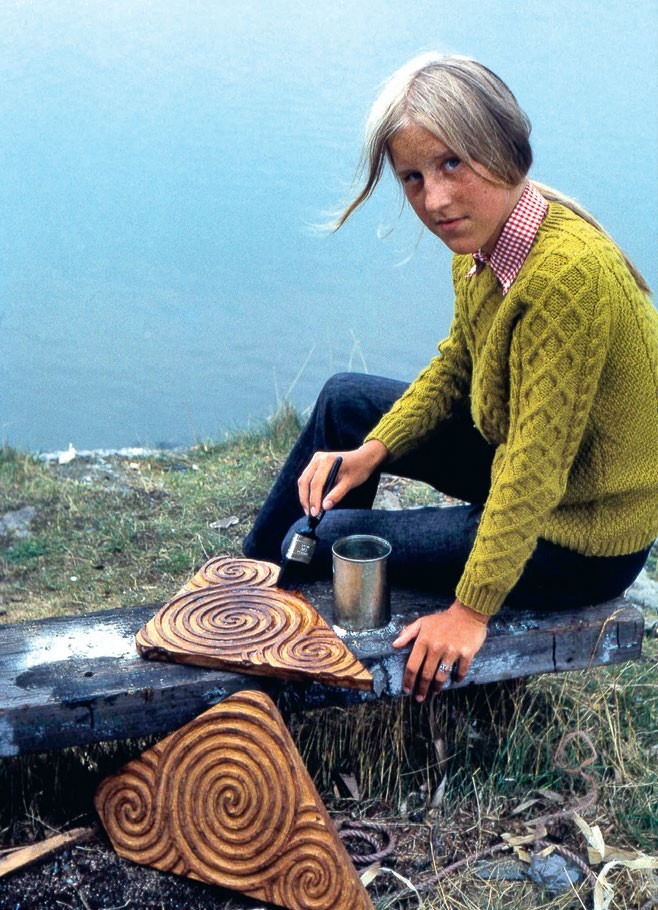

His personal life was unconventional as he was living with two women in the 50's that shared him. He married one of them, Jutta and after her death he married the other (Ruth), but was openly in relationships with the group of another three young women who also lived with him and were soon joined on Tehini by a 19 year old Hanneke Boon, who was still a school girl when she first met him in 1967 visiting with her father and mother who were early multihull enthusiasts as Hanneke and her sisters also became -they are all in the film about Tehini.

As the mother of his second son and later his wife and living with him for most of her adult life Hanneke was totally accepting of James' lifestyle and values as her own. In her obituary of James she wrote he continued to have multiple relationships all his life.

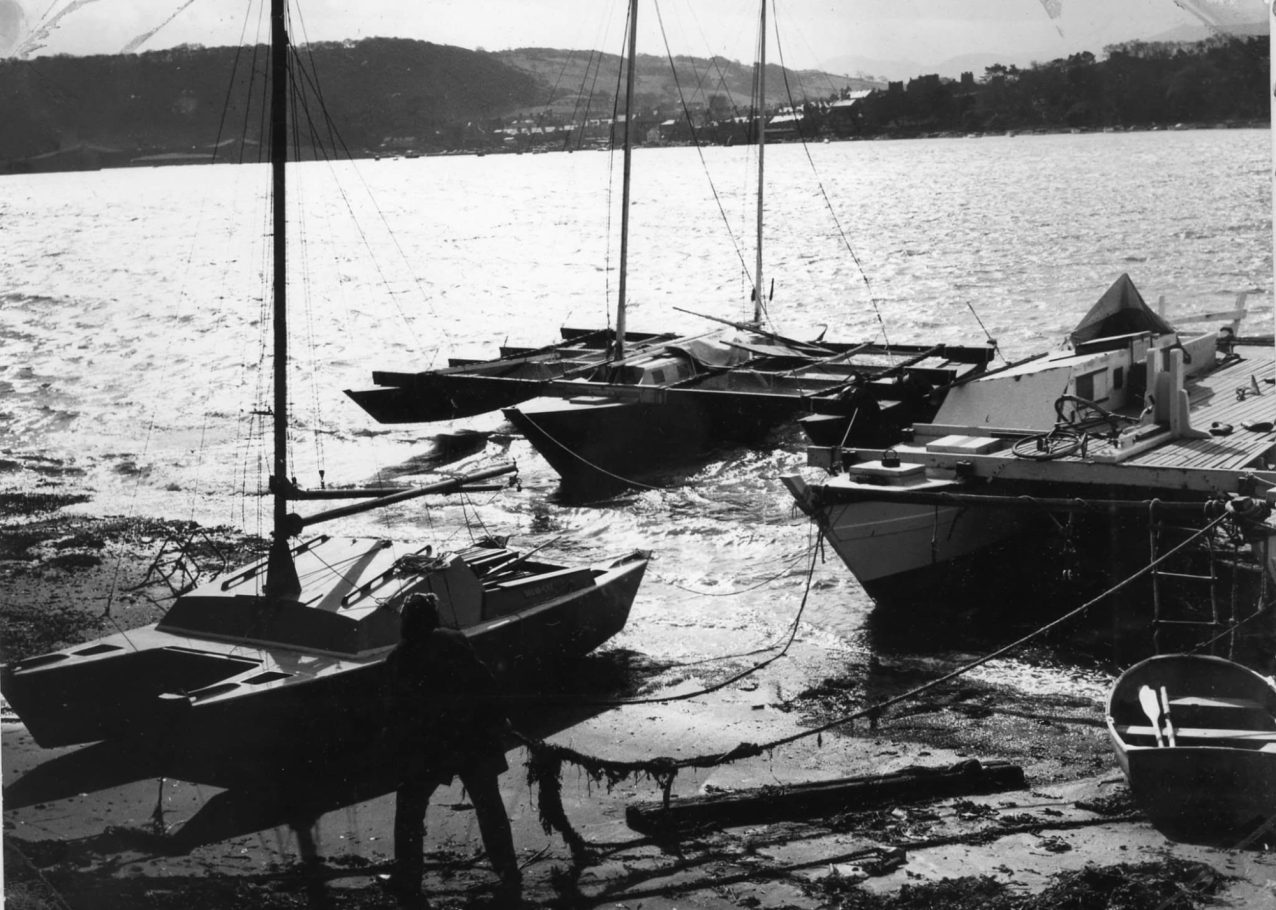

After Jutta died James and Ruth lived on Rongo on a beach in Deganwy, North Wales and brought up James' son Hannes (later known as Jonathan and a well loved GP in Manchester). James then attracted a number of other young women to join his life (including Maggie, Leslie and Nula) and by 1968 when Tehini was built there was a large group on men and women around him. Hannes was a feature in James' family references and seen in film and pictures of Tehini at the helm in 1969. He is photographed in the Tehini pictures in the 1970 period but was not it appears on the 1973/74 voyage. I guess Hannes went off to University and a conventional life? I wonder if he was a sailor like James?

After completing Tehini James lived on her for ten years with his women companions and Hannes. They moved from Deganwy to Milford Haven where they established an office ashore. In 1976 James bought a plot of land with a run down cottage and a quay in Killowen Ireland. James wrote of his idealistic vision for a base with builders and enthusiasts gathering to celebrate and build multihulls to the Wharram designs and build a seagoing community. They worked on a grp foam sandwich prototype for the new Pahi range and built a Proa for racing. The problem was that a postal strike isolated them as did the distance so that the visitors attached by the growing Wharram legend did not come and their mail order catalogues and plan business almost died.

Sadly the relationships between James and Maggie, Leslie and Nula also broke up; James telling his friend Jim Brown that three of his five "wives" had divorced him. How many more women entered his life after that I do not know but its is likely there were many more but the loving Ruth and loyal Hanneke stayed with him to the end. Ruth died in 2013 and it is clear that she was very much the power behind James and held the plan business together for many years, but Hanneke is also the artistic and designing talent that took Wharram designs on to success with the Tiki range and many more designs.

Even after James had moved ashore to his home in Cornwall there were stories of visitors to James' home being shocked to discover the man himself and various women "staff" wandering around naked or semi naked!

Returning from Ireland in 1979/80 to live on Tehini, James, Ruth and Hanneke were again running their business from an office in Milford Haven until they found a new land base in Cornwall in 1984 and lived there the rest of their lives. How the dismantling of the trading partnership of "James Wharram Associates" - James, Ruth, Hanneke, Maggie, Leslie and Nula (it was a Limited company actually called James Wharram Associates International Limited) was achieved we are not told but initially James wrote that they had no money after the split as the business assets were frozen so it cannot have been that amicable.

Why the relationships ended according to James' autobiography, related to his harsh behaviour towards Maggie and caused Leslie and Nula to side with her against him. He said he was too ambitious and hard driving about the business and failed to give her the love and support she needed at that time. Added to the situation was the almost total collapse of the business due to isolation, and a legal dispute that stopped them building the planned Catamaran base. Failing to either earn money from chartering Tehini so people could sample the Wharram Life in paradise (or at least St Lucia) or to sell her to release capital may have added to the implosion in the relationships.

Maggie had sailed with James on Tehini in the 1970 RBR and in 1978 she crewed with Bob Evans and the boat broke its rotten beams (a common Wharram design failing unfortunately). She also capsized the Wharram Proa and from what James has written it was a very bad time for her. Perhaps that drove her into another man's arms for the sympathy she needed. Apparently none of James or his companions relationships were necessarily exclusive according to what Hanneke has written.

I do wonder how multiple intimate relationships in a group like that can provide the individual emotional commitment and personal support that most people need in life partnerships -the reason that most people do get married or at least enter partnership relationships with one other person. The evidence in James'book suggests that it did not do so when one person is in relationships with five others at the same time (what most would think of a a commune).

James was a friend of John Seymour the BBC journalist, self sufficiency "Guru", philosopher, political activist, artist, sailor and larger than life author of 40 books who had a tempestuous personal life with a number of marriages and divorces, multiple relationships and children with different partners.

In the 60's and 70's John was living on a farm in Pembrokeshire (where James was also based at Milford Haven) where he had created a 'Centre for Living' and gathered a commune of people around him practicing self sufficient farming and an unconventional life style.

Clearly personal relationships became complex (and financially running the farm it seems that John was not adept and nor was he a faithful husband) leading to his long suffering wife and co writer Sally, leaving him. John then decided at the age of 70, in 1984 to leave his family and their life on the farm and make a new start in Ireland with his much younger companion Angela who had come to live on the farm aged 14.

John's biographer* wrote that James Wharram was an "eccentric" friend of John's who was a "serious drinker" who loved a good time; the biography was written after meeting James to gather material about John - who died in 2004. The book does say that James' life in Ireland ended when another man took away "one or two" of James' women.

We also know from this that James took John and Angela to Ireland to show them his cottage and John and Angela then rented the cottage from James before buying it. John's years in Ireland are the subject of one of his books "Blessed Isle". John who was without doubt an eccentric also refers to James as being his somewhat eccentric friend. John was certainly a serious drinker himself spending a lot of time in pubs and was a gregarious and larger than life character. He was a radical thinker, studied Marx and Lenin and was against consumerism and the loss of rural traditions. He was no supporter of authority or the English state so he really felt at home among the Irish people who had suffered so much at the hands of the English State, and the English ruling class.

John campaigned on Green issues and was prosecuted in Ireland for political activism that caused criminal damage to GM crops.

An interesting picture of James' character emerges. He was a man who went to college after school but chose to quit his further education and go travelling -an early backpacker. He worked in relatively menial jobs on building sites, deckhand on fishing boats, Thames barges, and labourer in boatbuilding factories.

Yet he is also an impractical dreamer that relied on his women to deal with everyday life practicalities like his clothes, paying the bills and providing food. It was Ruth who ran the plan selling business and kept in touch with the builders. He never learned to drive. He was on the one hand a friendly, gregarious and sociable man who loved to drink and dance; he certainly was a story teller; a man with a twinkle in his eye for pretty girls although one female Wharram builder (Heather Whelan in her book "The Voyage of Iki Roa") described him as an "unlikely Cazenove" and thought it was a mystery how he attracted so many women. She describes staying at Devoran and James' habit of answering the door wearing only a sarong unnerved her visiting parents who thought he had just got out of bed until they went in and found a house full of almost undressed people.

She describes James as regaling them with stories while it was Ruth and Hanneke that were being helpful and useful in a practical sense. She refers to James' "harem" being "continuously full". And "there never seemed to be a shortage of beautiful young women building James' latest boat..". She thought he genuinely liked women and his charisma attracted acolytes..".

But reading James' articles and correspondence with the AYRS and in Multihull International Magazine he also came across as someone that was arrogant and critical of others, writing in a way that showed his belief that he was right and other designers were wrong on stability, hull shape and indeed the entire philosophy of catamaran design. James' massive ego shines through it all -a man who seems wholly confident in his own ability and determined to prove that he was right and that the others would soon find out they were wrong!

He could be unpleasantly personal in his attacks on others in public correspondence - if he could write like that in public I wonder what he was really like in private?

His superior stance against others was not something likely to endear him to them. Equally his claims for his designs sometime verge into the delusional - for example the outrageous assertions that Tiki Roa would be competative in the 1966 RBR or that Tehini would keep close behind the Whitbread Race fleet in 1973.

Never formally educated in design or the science of boat design, James clearly was well read with philosophical references in his writing. How expert in the skills of Naval Architecture - ship hydrostatics, stability, resistance, propulsion, structures, and marine engineering - he actually was, I do not know. Certainly he had read Howard I Chapelle's masterpiece on yacht design quoting it when he originally started to develop his theories about multihull stability in the late 60's.

In Two Girls, Two Catamarans it is clear that Ruth did the maths of the design and was pleased that Rongo floated to her marks as she had calculated. James says that he designed Rongo but the building plans were drawn retrospectively by Jutta. James said that he was not a draftsman, so I can only assume others drew the plans after Jutta died until Hanneke joined the family. It was Hanneke that he relied upon to draw the designs thereafter. Even in the plan catalogues and study plans her influence is clear.

So today it is actually Hanneke that is an experienced designer and has emerged as the architect of the building plans, design book and study plans behind the last 50 years of Wharram Designs. Many have praised her work and her books of building plans comprise an illustrated course in boat building.

Even after following his career and adventures for many years and reading all his books and other writings and those of Hanneke and others about the Wharram "family" the feeling persists that there is a lot I do not know about the life of James Wharram. To a large extent his books only present the positive image he wanted to present of himself but then is that not always the case with autobiographical writing?

I have read an account online by Peter J Marsh of his visit to the Wharram group at Deganwy when he bought the floats from Tiki Roa and built an unsucessful catamaran from them. Peter knew Derek Kelsall and helped build Toria and his blog has a fascinating account of meeting him at the 1964 RBR. He also knew Bill Tillman and sailed with him. Then he wrote that he followed James Wharram to Deganwy after meeting him at an AYRS meeting in London. He commented: "Tilman and Wharram are both men with a larger than life reputation. In reality, things weren’t quite as romantic or functional as you might expect."

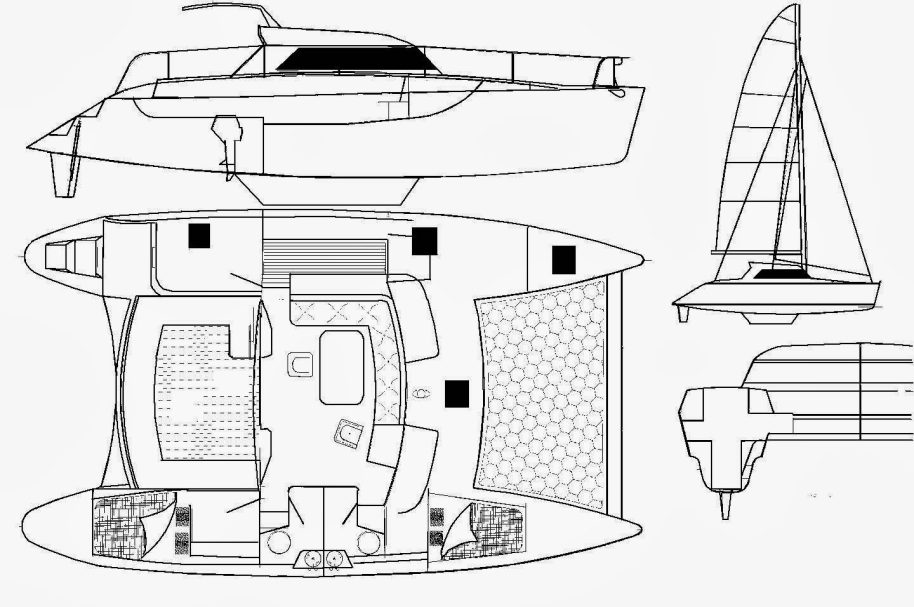

The commercially successful multihull yachts that are dominant in the World of yachts today follow totally different design principles and styles to the Wharram designs which even today are unique. James consistently criticised the design concepts that today dominate the multihull scene; these are mainly the big roomy cruising catamarans with amazing bedrooms with ensuite showers and bathrooms, large windows and palatial saloons (or 'deck cabins' as he called them) with patio doors. (See the MOCRA article I have included below in the gallery).

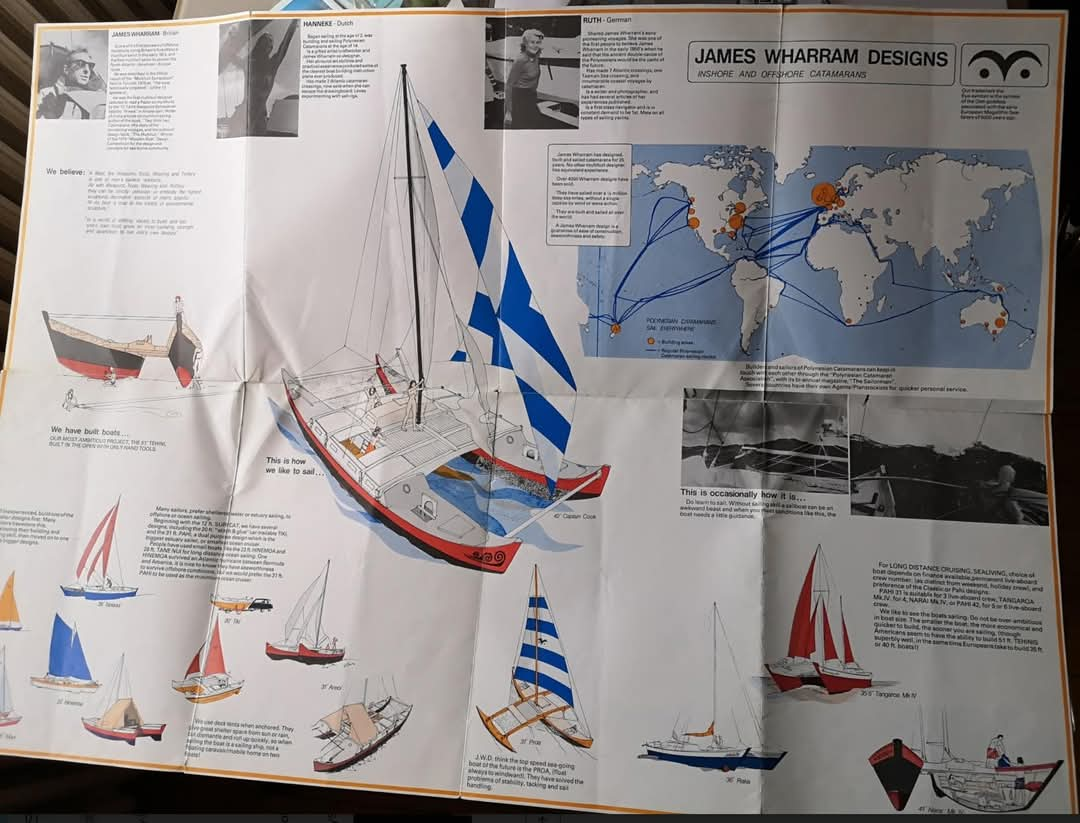

According to James most catamarans were based on Western design concepts whereas he advocated entirely different types of boat with low "V" shaped canoe hulls -, bolted and later lashed to beams that were flexibly mounted, with minimal accommodation all in the hulls or little deck "pods" lashed to the beams and low gaff rigs.

James claimed the distinction of selling more than 10,000 sets of catamaran plans for home construction. This is almost certainly more than any other home build multihull plans seller has achieved.

Some say that James sold more than boat plans and his buyers instead bought into his entire philosophy rejecting "land" values of Western society. He cultivated his role as the great wise man, Jim, leading his tribe of Sea People to a better place than suffering in consumption driven wage slavery of western society that was also destroying the Planet. He believed in the 70's that modern society was doomed and that people could form homesteading self-sufficient communities living on their boats - he was a survivalist in today's terms.

Today Hanneke runs the business with their son Jamie and I imagine his name and his designs will live on, but such is the way the boating market has changed since the Wharram heydays of the 60's and 70's the market for self-build has declined. If you want to go cruising the second hand market is awash with used production boats of all kinds. No longer is buying a pile of plywood and a set of plans the primary route to ocean cruising. Now that journey begins with advertisements and brokerage websites or bidding on E-Bay.

Anyone that chooses to build their own boat now, will do so because they have particular requirements -the desire to use the best modern design and materials that will not be present in older second hand designs, the desire to build using the latest technology and design and other specialist interests and requirements.

The self build market is more sophisticated now than in the 70's as are the way multihulls are designed and built. The levels of technology and construction have moved on a long way even since the latest Ocean Cruising Wharram catamarans (Tiki 38 and Tiki 46) were designed some 30 years ago let alone the sheathed plywood Wharrams of the 60's and 70's. Comparing for example a 70's Wharram build with someone building the latest Kit boat from Schionning or similar, the end result and level of skills involved is lightyears apart.

Even 25 years ago many home builders or as is often the case, owner managed building projects with additional or contracted specialists, were building some very sophisticated craft. A good example is to compare self built Kelsall Suncat 40 Tootega (ex Lady Jane III ) with a self built Wharram catamarans illustrated in the gallery below. Also many Farrier trimarans were self built achieving very high standard sophisticated racing and cruising multihulls; likewise Schionning designs and others that are sold as kits. A different approach the Wharram one.

A choice to buy Wharram plans to build your own boat is now therefore, more than ever, a lifestyle choice. It will probably be based on sustainability and green belief systems and attract those who are either short of money or unattracted to modern "plastic" boats because of aesthetics or these days on green moral/philosophical/political grounds.

Keen racers and those looking for modern high performance sailing will not choose a Wharram design, and sophistication, and luxury do not apply to Wharram designs either. That said particularly with smaller sizes there is no doubt still a market and great interest in Wharrams' designs. The attraction of the Wharram designs is different to that which will draw in experienced multihull sailors or racers or dinghy racers looking for a cruising boat. They are likely to be attracted to more high tech designers and lightweight craft with high tech sails and equipment.

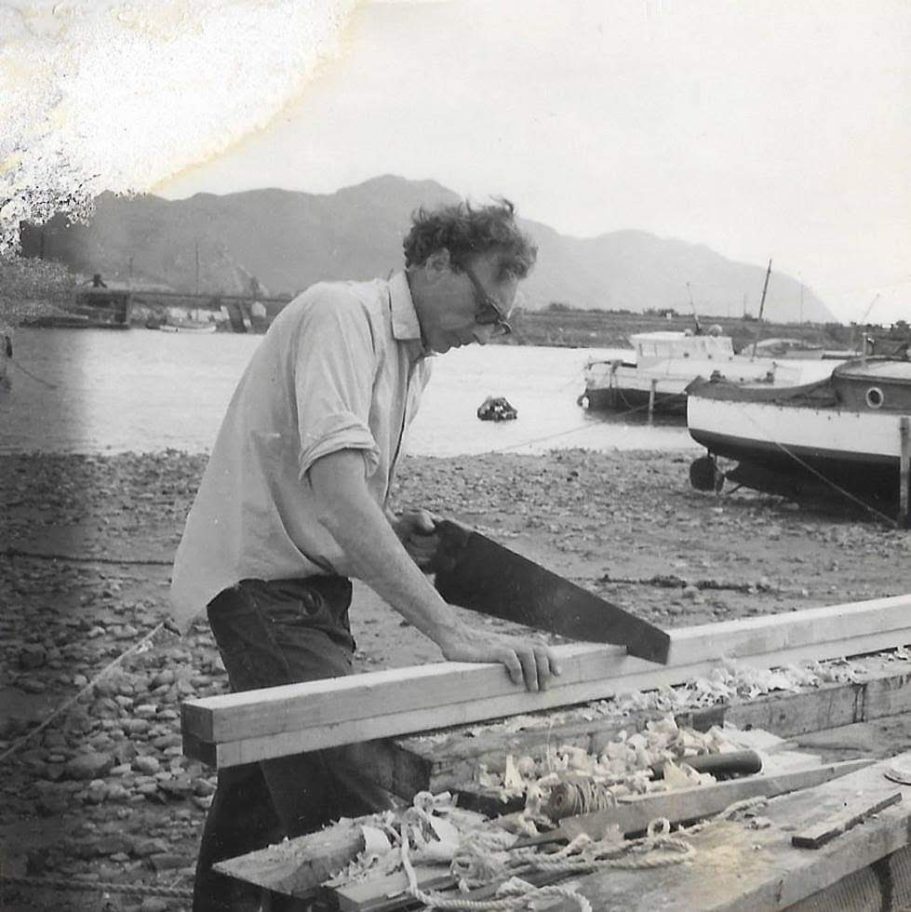

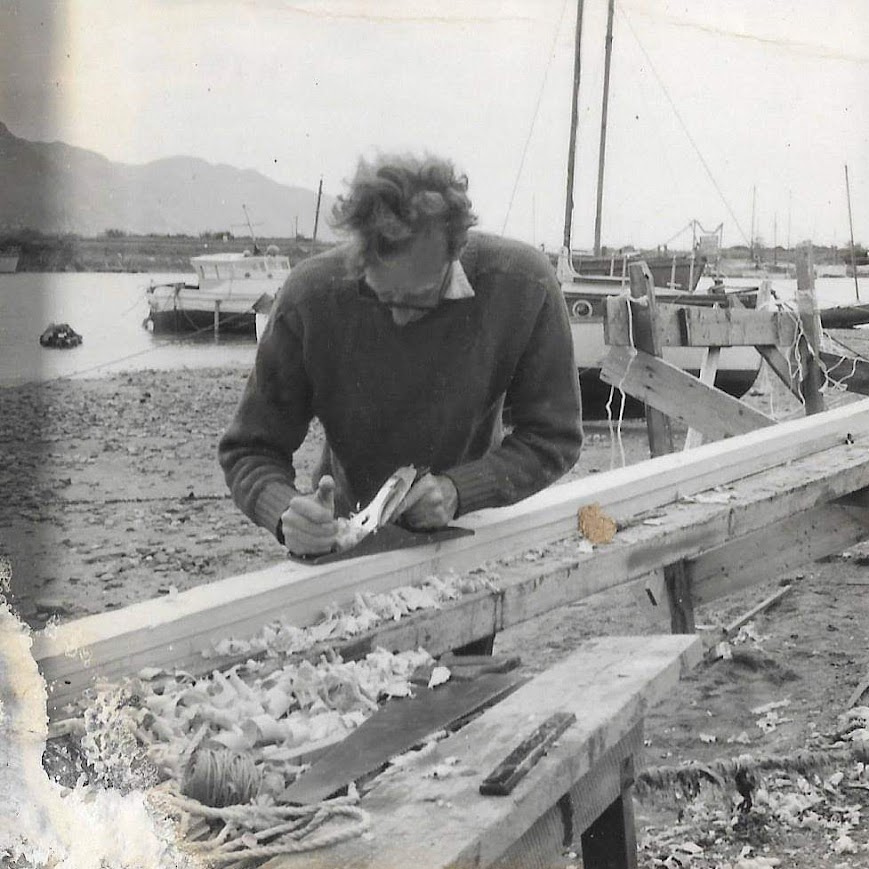

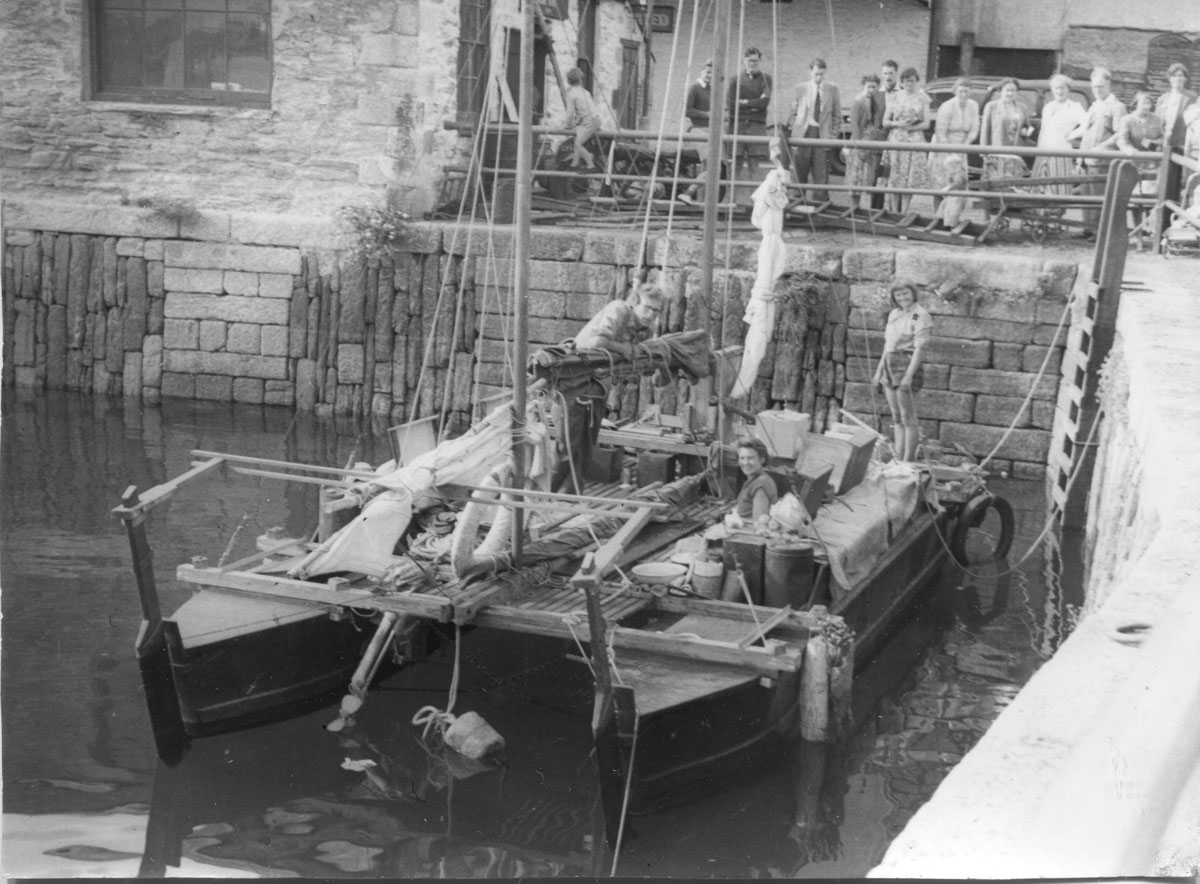

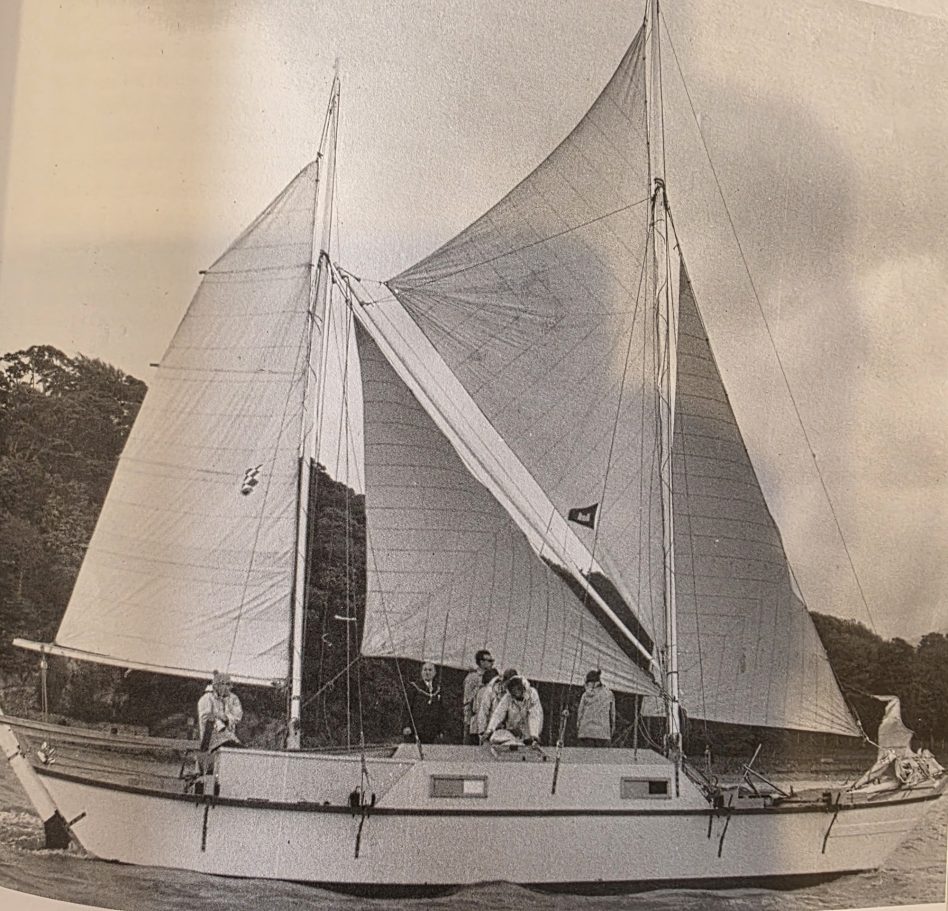

The first Wharram design was the 23.5 -foot Tangaroa on which the three adventurers Jim, and his two German girlfriends, Ruth and Jutta sailed to the West Indies. Flat bottomed box section hulls resembling coffins, a slatted platform between them and held together with chains, the craft had a tiny rig and cabins like rabbit hutches and their voyage must rank as one of the bravest in the history of modern boating.

James was a self styled Maritime Archaeologist, inspired by reading about Polynesian canoes and by the voyage of Eric De Bischop he was on a mission to establish that a catamaran was a low cost safe and seaworthy vessel. A Pathe News archive film at the time showed them before they departed from Falmouth in 1954. Conventional wisdom at that time was that the vessel would be smashed to pieces by the Atlantic waves and going to sea on it was simply suicidal. Conventional wisdom was wrong! They sailed Tangaroa to Spain, the Canaries and across the Atlantic to Trinidad.

It was a very hard voyage. The bravery and strength of character that James and Jutta and Ruth exhibited was exceptional.

The catamaran survived the voyage but succumbed to Teredo worm lacking antifoul and or copper plating below the waterline.

She was abandoned (a feature of James' relationships with all his boats unfortunately; Tangaroa abandoned; Rongo given away when she was rotten only to sink when she was taken to sea, and Tehini burned on the foreshore by James' Devon home). In Trinidad the trio built a raft houseboat to live on where Jutta had his baby, Wharram’s next project was to design the 40-foot Rongo.

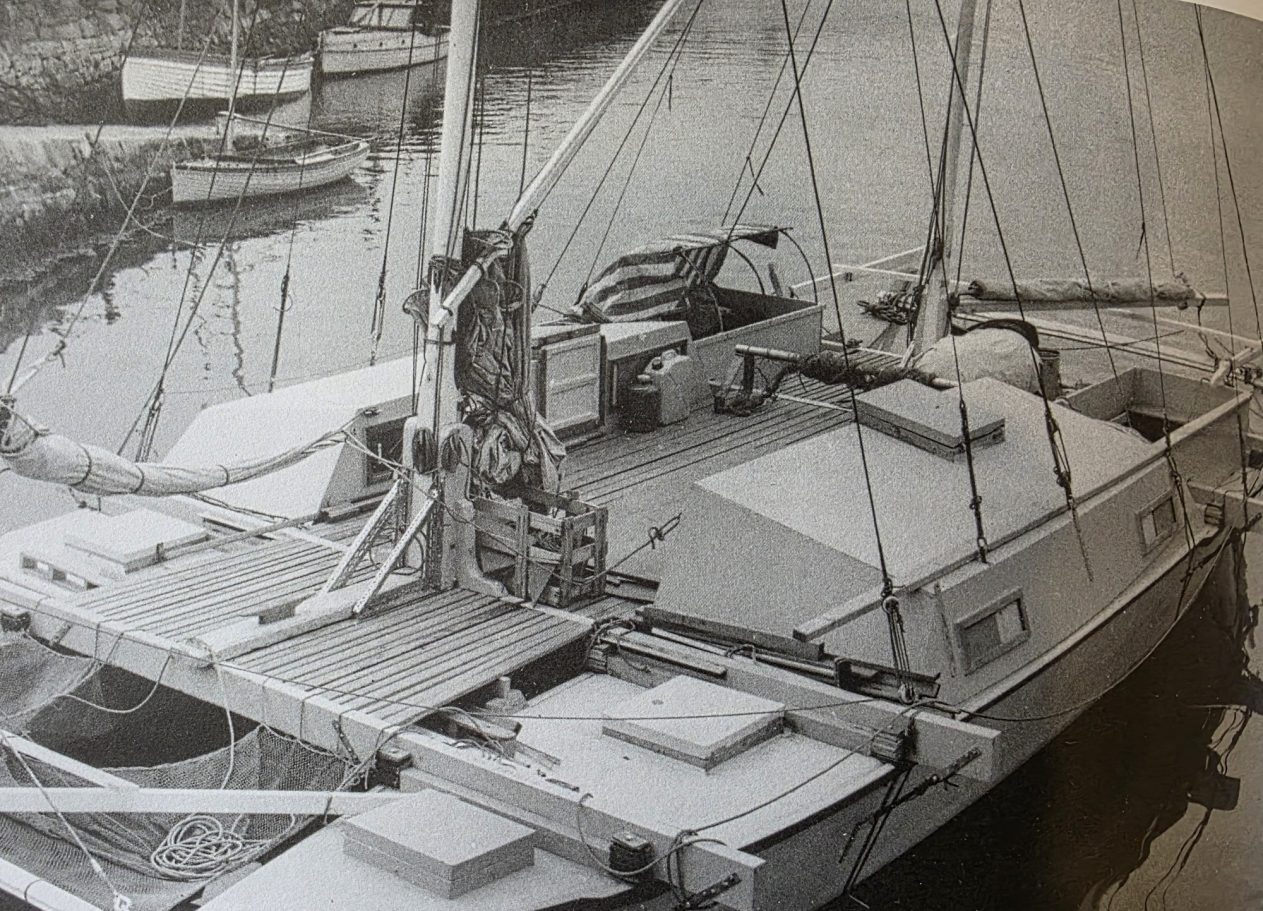

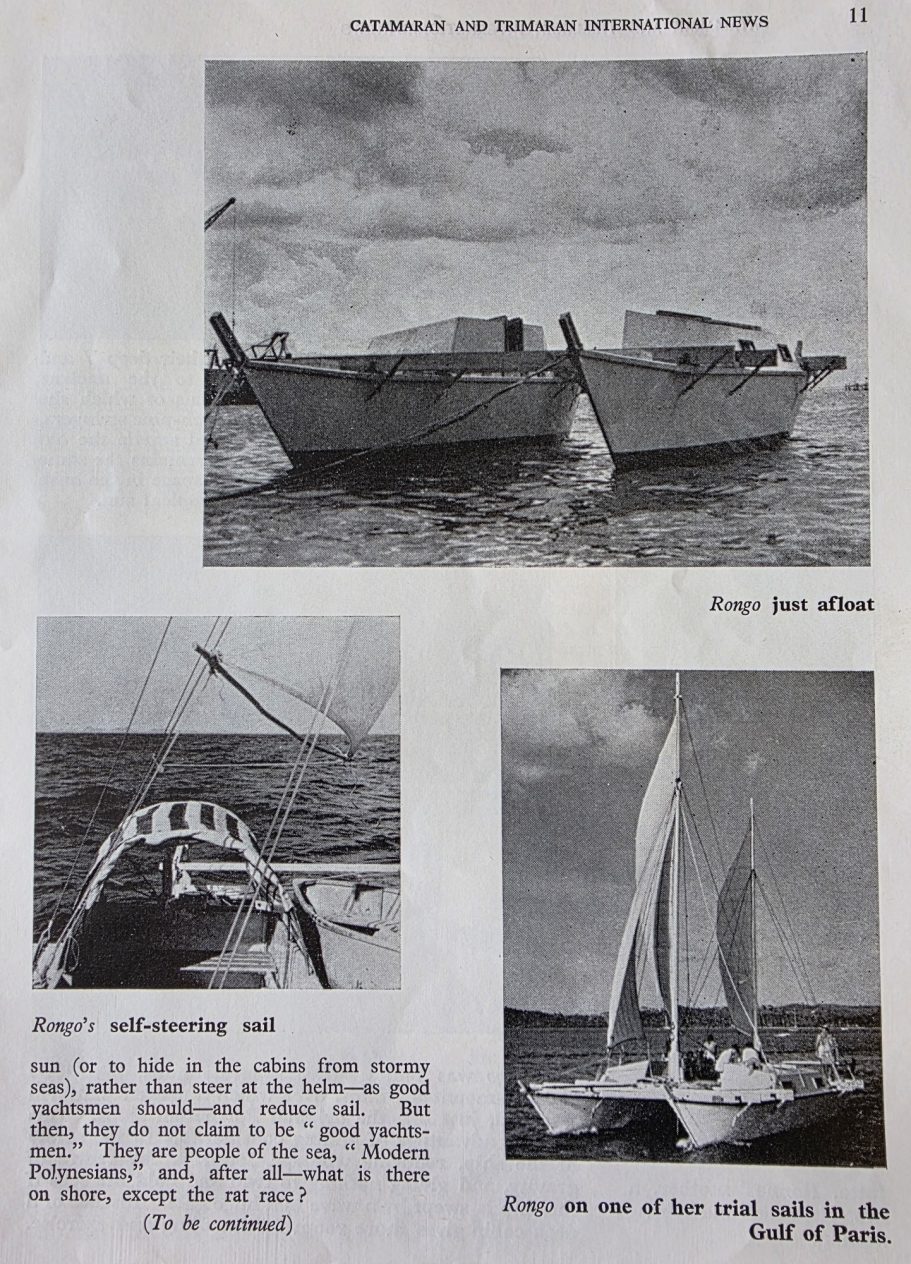

This brilliantly inspired 1958 design was similar to De Bischop's Kaimiloa and is without doubt the basis for every Wharram since and if you look at her and the later Tiki 38 and 46 (1990's) the family likeliness shines out although the construction methods are now more modern ply epoxy glass sandwich and the build method evolved to be suitable for home builders but more sophisticated and nuanced than the designs that Wharram marketed in the 60's.

But most of the essential Wharram design features that were present in all his designs afterwards were established in Rongo: narrow deep V hulls double ended with canoe sterns, flexibly mounted beams with a slatted wood+ open deck and no keels or dagger/centre boards, low aspect rig and fully battened sails with separate accommodation in the hulls. Photo's show a boat very similar to the later Tiki range of the 80's and 90's. She was a revolutionary piece of design that is still basically ignored by yachting history! Yet she was probably the most successful seaworthy Ocean going catamaran in the northern Hemisphere by several years and deserves greater recognition.

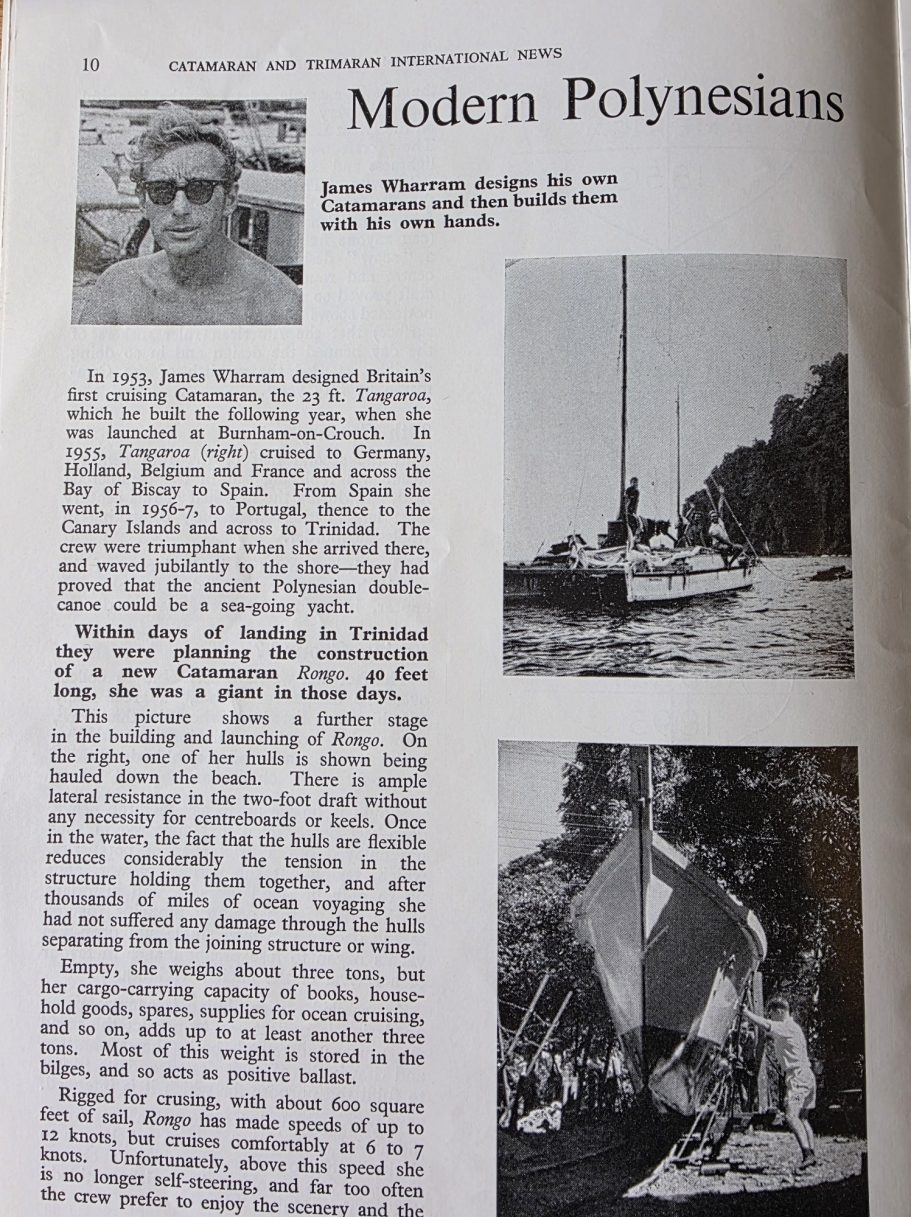

In the very first issue of a privately published UK magazine Catamaran and Trimaran News in Spring 1964 James and his catamarans were featured some 11 years after he had designed his first catamaran and 6 years after Rongo was built. The article is reproduced in the gallery below.

After a tough voyage from New York to Ireland in 1959 Rongo was readied for around the world voyage in Wales and then sailed to Ireland. James married Jutta in Ireland, and they all set out around the World. Jutta had already shown signs of developing mental illness -possibly related to trauma caused by her experiences in Germany during the War. Jutta’s death by suicide in Las Palmas ended the voyage and although Ruth and James still crossed the Atlantic to Trinidad they decided they could not go on without Jutta. They sailed back to Ireland and then Wales in 1962. They had now sailed Rongo three times across the Atlantic covering over 12000 miles in her.

After his abandoned World voyage James and Ruth lived with James' son on Rongo on a beach in North Wales. It must have been a very hard life indeed in a cramped and spartan plywood catamaran without any modern facilities whatsoever. James had clearly been traumatised by Jutta's death. In his book he cited excerpts from his diary showing how deeply depressed he became in 1962. His dad encouraged him to design him a small cabin catamaran that could be towed behind a car. James had built this but father and son then capsized on its first sail. He had to widen the boat to make it stable.

In 1964 James designed the 34 foot Tangaroa for a friend. This was followed by a 22 foot Hina and this led him to start publishing a design brochure and advertising in Yachting Magazines.

Both designs were really quite simplistic with spritsail rigs that were not a concept that could achieve the sailing performance sought by most multihull designers and owners.

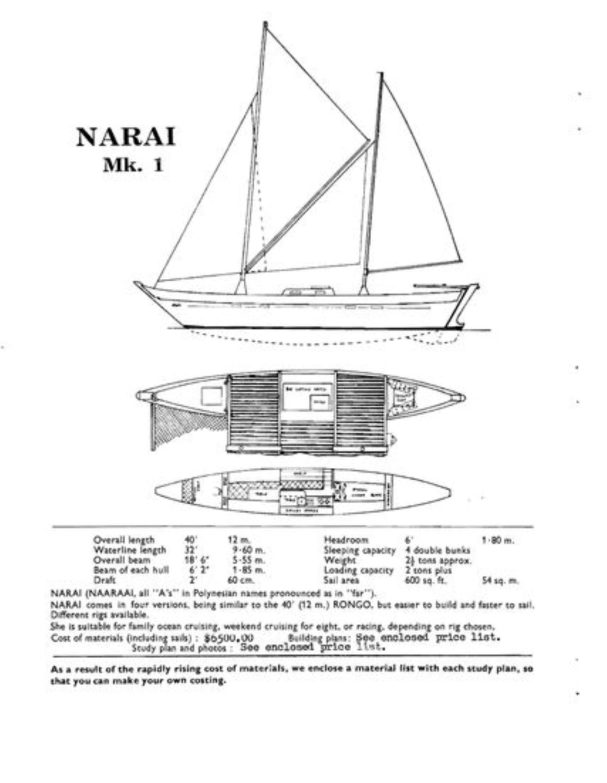

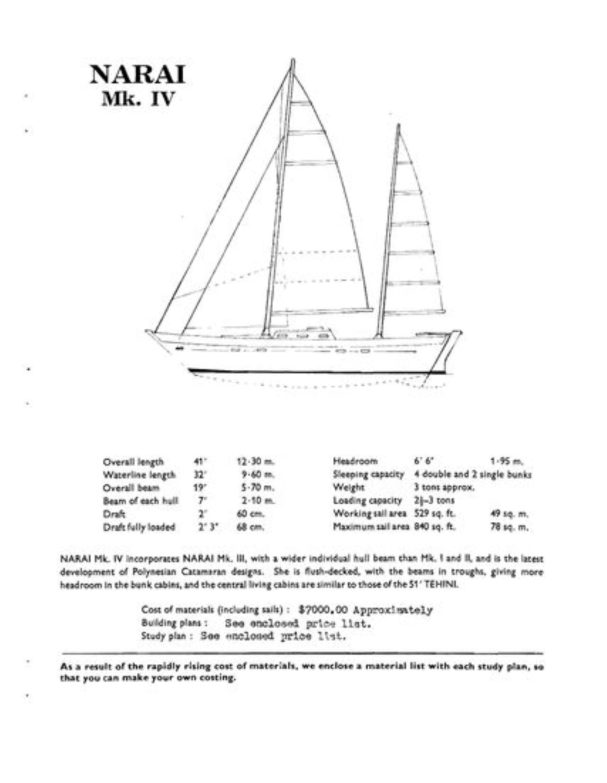

He followed this with the 46-foot Oro Ocean cruiser and replaced Rongo with the 40 foot Narai. Above the Hina he designed a 27 foot two berth ocean cruiser the Tane. He published articles in yachting magazines and his self-build design catalogue started to achieve sales and boats were built, and people sailed the Oceans in them. Some found these designs to be slow in stays or difficult to sail to windward . The earlier primitive rigs were not optimised for performance and the V shaped hulls without any external keels or dagger or centre boards were poor performers up wind and indeed high wetted surface made them sluggish and often difficult to manoeuvre. However James had developed a simple building method (revolutionary in his eyes) so someone with no boatbuilding experience could build a catamaran.

In 1965 James had built a trimaran called "Tiki Roa" and entered the 1966 Round Britain Race with another German girl as crew. Writing to AYRS and Multihull International, his ambitions for the double outrigger were optimistic to the point that reading them now seem delusional- he was very carried away by his own ideas and thought the boat would be competitive against the new Iroquois production catamaran. He wrote that only the sponsored 40 foot racer called Mirrorcat entered by Rod McAlpine Downie would be faster. Of course Derek Kelsall's new 42 foot racer Toria was victorious in the Race setting the style for most future racing trimarans.

Reality was that the small spritsail ketch rig and V shaped hulls meant Tiki Roa was never going to succeed as a racer. A commentator in the press likened it to a fishing boat and noted how poorly it pointed compared with the relatively sophisticated yachts it was racing. The boat had arrived at the start on the back of a lorry unprepared and untested. For James the race was over quickly when the daggerboard broke.

He did concede in 1966 that Derek Kelsall had "done a better job" with Toria's design than he had with his trimaran but then given that Tiki Roa retired and limped home to ignominy after being last in the fleet on the first leg and Toria romped home a day ahead of the fleet, is rather an understatement.

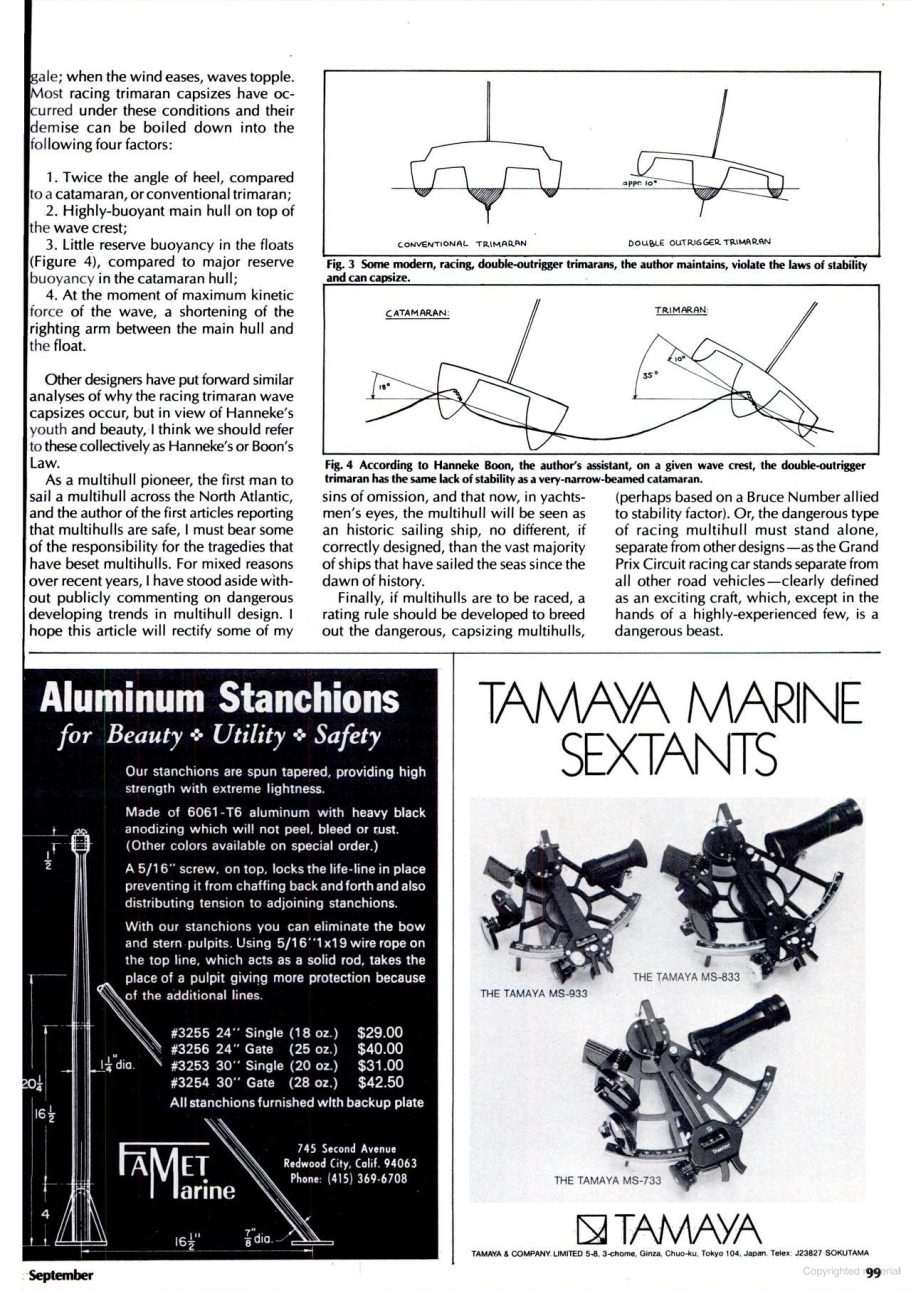

Post race James abandoned the trimaran or double outrigger concept and indeed became very much against them as designed by Kelsall, Crowther and Newick in particular. James rather simplistically argued that wave capsizes only happened to what he called double outrigger trimarans.

It was Derek Kelsall who sarcastically told the audience at the 1976 Multihull Conference* in Toronto, Canada that the Tiki Roa trimaran had established that James was definitely NOT a trimaran designer. Looking at it objectively it was a poor design but James used his bad experience with it to be critical of double outrigger trimarans in general. By this he meant those built in the new Toria style of open decks and outrigger floats riding high sailing on only the main hull and the lee outrigger.

He distinguished these from the older style of cruising trimaran of Jim Brown, Norman Cross and others that had large floats and were designed to sail with all three in the water. It shows his arrogance at that time (1966 to 1977) that he cited the defects in his own design as being characteristics of the type rather than simply the result of his bad design.

In his online column many years later in a tribute to Tony Bullimore James wrote words to the effect that he met Tony when he was struggling with an old trimaran "past its best" in 1972. That boat was the then six year old Toria which was lost only because an oil lamp fell over and caught the yacht alight. Her sister ship Trifle is afloat at 57 years old whereas many Wharram designs in plywood lasted less than 20 years (eg Tehini whose useful seagoing life was 16 years). Had Toria had the updated rig (as fitted to Trifle and Trumpeter at the time) I am sure Tony would have found her fast and competitive. Triple Jack the 45 year old Kelsall trimaran that is essentially the same design concept, was (with modern sails) still winning races in 2024.

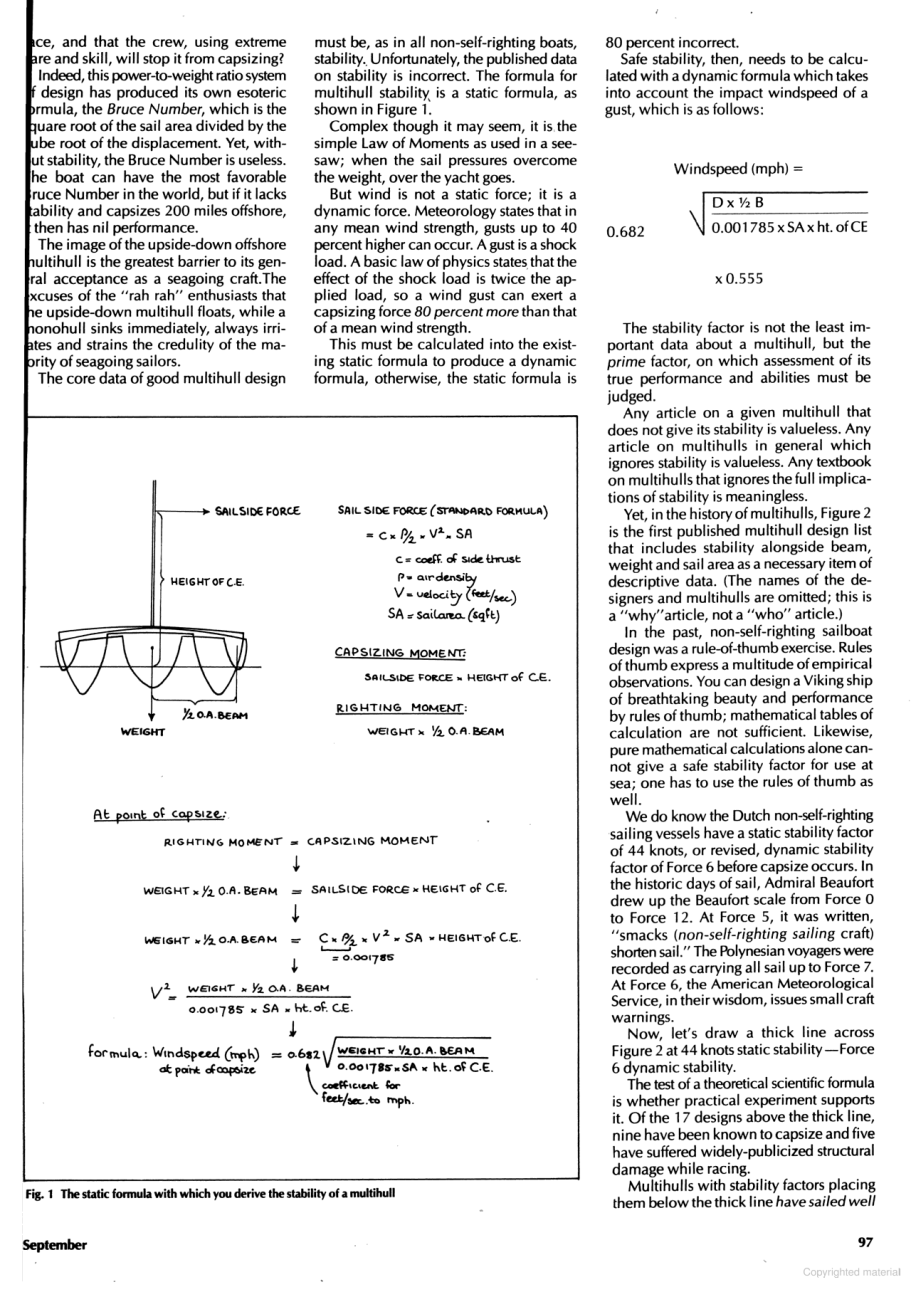

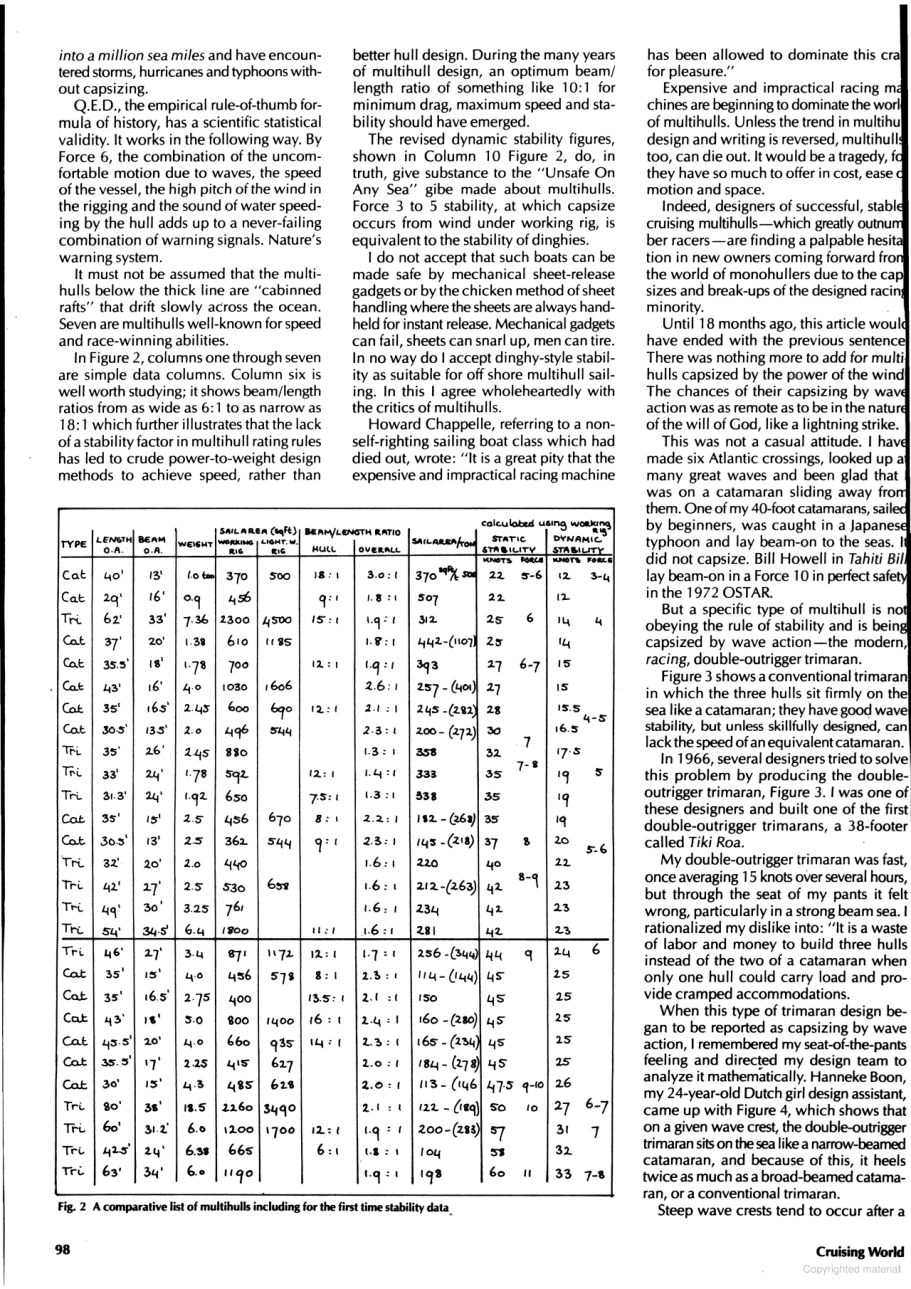

James wrote a seminal article published in the UK and possibly other yachting magazines in 1977 arguing the case for stable multihulls and on wind stability where he distinguished between static and dynamic stability. By the latter he meant that the calculated wind speed that would capsize a multihull had to allow for gusts. Effectively for example a catamaran that was calculated to be stable up to a tipping point of 30 knots should be treated as being only stable up to 20 knots because a 20 knot wind could contain 30 knot gusts.

His thesis was always that a safe multihull must be stable to a Force 7 wind (ie 28-33 knots). Using his dynamic theory this mean the boat would have to be stable to over 42 knots of wind. It is possible to summarise this by the idea that a multihull reefs for the gusts whereas a monohull reefs for the average windspeed.

Even that is too simplistic really because good seamanship and sailing skill involves feathering the sails in gusts if hard on the wind or if as most of us prefer you are not hard on the wind bearing away free in the gusts and enjoying a multihull's speed and acceleration.

Add to that the fact that the formula's for stability do not in many people's opinions represent the Real World stability very well.

But in the article he (and Hanneke who co-authored it) then attacked double outrigger trimarans that sailed on the main and the lee hull saying they were dangerously prone to wave induced capsize because of the way they heeled more than a catamaran. He suggested that the greater width between the two catamaran hulls and the narrower width between main and lee hulls of a trimaran made the latter less stable causing them to capsize. The argument was that the catamaran sat wider and raft like on the wave and was thus more stable than the main hull and outrigger of a trimaran sitting on a wave (ignoring the windward hull).

That analysis appeared to be flawed in the sense that the righting arm only takes into account lss than half the overall width of a catamaran (from the centre to the centre of the lee hull) and a similar length trimaran will usually have a wider righting arm (between the centre of the main hull and centre of bouyancy which is usually the centre of the lee float) than a similar length catamaran as long as the floats have high enough buoyancy to support more than the total displacement of the boat.

The main problem causing the capsizes James referred to was almost certainly the trend toward lower buoyancy outriggers at that time. As the lee hull submerges the centre of buoyancy will move towards the main hull shortening the righting arm as happens when a catamaran lifts the windward hull. This has been demonstrated by tank testing and mathematical analysis. James and Hanneke were right that some trimarans with low buoyancy floats (like Tiki Roa) were less stable in waves but the causes of the problem were not quite correctly analysed in the article. Interestingly based upon his empirical experience crossing the Atlantic and the Pacific in his trimarans Arthur Piver was very much against low buoyancy floats in the 60's before the issue was raised by James or anyone else while Derek Kelsall, Dick Newick and Lock Crowther embraced the concept.

However James and Hanneke did observe that the added heel angle of a trimaran can be detrimental; and the fact that this causes an added rotational moment has been identified as a very good reason not to lie a hull or broadside on to breaking waves in a trimaran especially if it had low buoyancy floats. Many years later in the Design Book they correctly wrote that it was a buoyancy issue that caused some trimarans to be capsized by waves.

Now however it is accepted that in any multihull it is wise not to lie ahull side on to breaking waves of any size greater than the beam of the boat because that seems to be the wisdom of the accumulated experience of many very experienced sailors and also the results of the Wolfson Centre's tanks tests and scientific analysis adopted by the MCA and other agencies around the World since.

There are cases of catamarans looking after them selves in severe storms - Richard Woods abandoned his 32 foot Eclipse in the Pacific and the yacht survived as other buoyant catamarans have too. A Roger Simpson design catamaran did the same after the crew got taken off in a gale off New Zealand but the fact remains that all craft can capsize and large breaking waves can be fatal for all craft. There are examples of safe solid cruising catamarans (eg the Catalac 9 meter, a Prout Ranger 31) and others more recently being rolled over by breaking seas in shallow waters. Many an analysis of a capsize shows that it can be a combination of wind and waves.

The argument expressed by James that essentially catamarans are wave stable like rafts and only "spidery" double outrigger trimarans get rolled over by waves is not necessarily correct in my opinion. But equally a low hulled, wide beam Wharram catamaran with little or no superstructure and low masts will probably survive severe storms and waves as James intended and there are many accounts of them doing so.

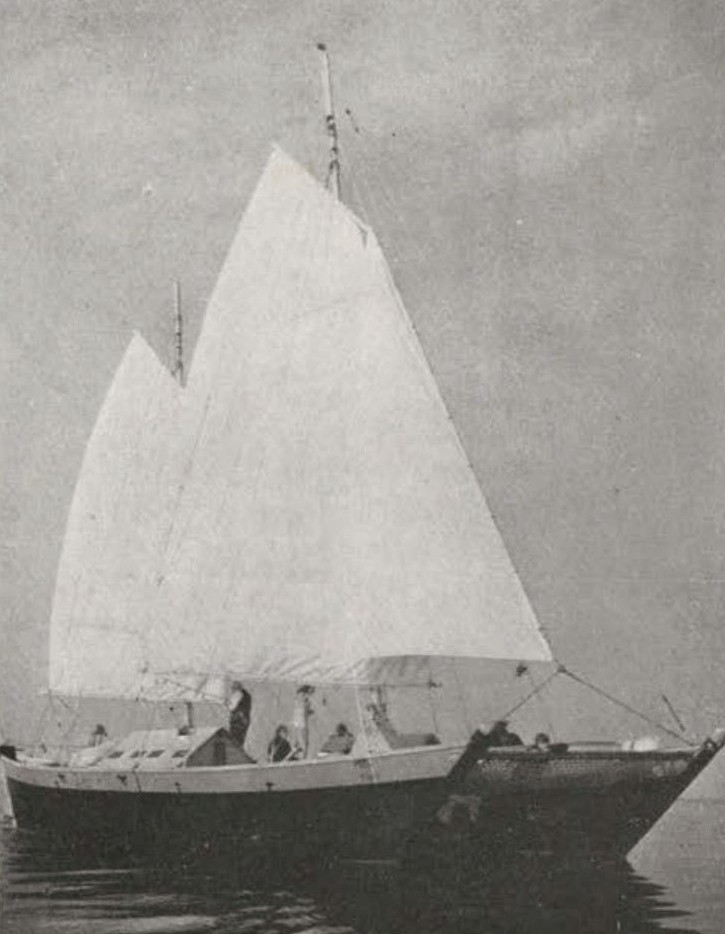

By 1968 when he designed and started to build his dream ship, the 51 foot Tehini James was emerging as a notable figure in the growing multihull scene in the UK and Worldwide. His boats were being built in astonishing numbers. He designed supposed racing variations -the 45 foot Ariki and 36 foot Raka.

The building of a 51-foot Tehini in 1968 to 1969 appealed to a lot of people's imagination. The film of this enterprise made by Ruth Wharram is now available on You Tube (link below). Establishing a commune like existence of men and women around him was an alternative lifestyle which is now branded as being a hippy one and certainly the image of Wharram catamarans was one of hippy boats for alternative people and life styles. Even before it was built James was advertising in 1969 that he and his "staff" were going to sail Tehini around the World.

Originally Tehini featured a Chinese junk rig - not a recipe for good racing performance and after James had written in Yachting Monthly of how brilliantly it performed and was so easy to handle it was, he abandoned use of it on Tehini for a more conventional Bermudan schooner and later a cutter/ketch rig.

The entry of Tehini in the 1970 Round Britain Race revealed that the boat was not capable of racing to windward in gale force winds - James had concluded after the race that the Junk rig was unsuited to the fast hull forms. He wrote of being unable to slow the boat down in the race and he only recommended the junk rig for the slower designs. Tehini was not able to sail well to windward with such a rig although later with the Bermudan cutter /ketch she reportedly sailed well and tacked positively.

It took four years for James and his crew to set off around the World. James wrote to Multihull international magazine saying that Tehini was going to be following the Whitbread Round the World Race fleet of big crewed mono hulls. He wanted to experience a family cruise against the the racers and said "I suspect that there may not be so great a difference between the average times". Once again as with his ambitions for Tiki Roa in the RBR he seemed to be fantasising, given that the fully crewed 80 foot mono hulls were twice Tehini's 40 foot waterline and mainly professionally designed and equipped racing machines with trained, experienced and very competitive racing yachtsmen on board.

Then, unfortunately Tehiniwas soon out of competition anyway because unforeseen design and construction faults in Tehini sent then running for shelter in Spain and hastily improving the design building in stronger supports for the loose beams and supporting shelves for the hull sides that were flexing.

The circumnavigation was again abandoned with Tehini sailing to the West Indies reliving the successful voyages of the Rongo. In 1975 they were back in Wales although Tehini was to sail across the Atlantic twice more while James and his women embarked on another naïve and idealistic scheme to create a land base in Ireland. It too would fail.

Between the 70's and 80's the Pahi range was evolved with hull shapes chosen to resemble genuine Polynesian concepts something they took further in the voyaging canoes they built for the 2008 Lapita voyage which was the antithesis of Heyerdahl's Kon Tiki expedition and proved the viability of double canoes with hulls based on examples of native canoes with traditional Polynesian style sails migrating East to West to Polynesia.

James, Ruth, Hanekke, Jamie and others sailed around the World in the 63 foot Spirit of Gaia between 1994 and 1998. They attended a Polynesian voyaging rally of canoe replicas in 1995. They were not made as welcome as they would have wished. Manchester's own Polynesian had called his business "Polynesian Catamarans" for many years (until he decided to call his boats "double canoes" rejecting the western term "catamaran") but a white Englishman was not as recognised as the great pioneer as he would have expected even after sailing half way round the World at the invitation of the organisers.

Wharram lived his entire life fighting the "establishment" on behalf of ancient Polynesian peoples and their sailing boat concepts and to suffer exclusion by those same people was an awful experience for such an enlightened man. It was a reaction to colonialism that the reawakened sense of their history, cultural and traditional skills were celebrated by the Polynesians and that the intervention of Westerners like Ben Finney and Dr David Lewis in the formation of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and its replica canoe Hōkūleʻa was resented by some of the people rediscovering their navigational skills and their history who wanted the voyages to be carried out by genuine Polynesians and not Westerners. That they did not appreciate James Wharram's contribution to proving that the double canoe concept was seaworthy was ironic given how James had lived his life dedicated to reviving this traditional form of vessel.

There is a lot of written material available now about the sea people of the pacific and their double canoes and navigation revival in Polynesia. This and the work of the Polynesian Voyaging Society is wonderful to see but it is a travesty that they fail to credit James Wharram's early voyages with the efforts he made to establish the seaworthiness of double canoes.

However generally James' work as a historian and pioneer of craft related to native craft and their evolution was recognised by other marine historians and those who study ancient seagoing history. He was a speaker at many conferences and contributed articles to debates about the development of ancient boats and the evolution of seaworthy modern multihulls from their native origins. He coined the phrase "appropriate technology" for his designs.

It is true that by the 1980's and since people have finally started to appreciate Wharram and acknowledge his achievements.

While the UK yachting community bought the grp catamarans from Bill O'Brian, Prouts and Sailcraft with their comfortable bridge deck cabins, showers and "bathrooms" with big galleys (kitchens) and dining tables; Bermudan rigs, fin keels and centre or dagger boards and the trimarans of Piver, Kelsall and Crowther, Wharram railed against these concepts arguing the superiority of his simple plywood V shaped hulls, lack of any protruding boards or keels small cabins and layout where daily onboard life took place on the open slatted decks. When he could not claim superior seaworthiness, he could say his designs were cheap and easy to build and he promised ordinary people the ability to build boats and live a fantasy-like lifestyle as "sea people".

The books "Two Girls, Two Catamarans, in 1969 and "People of The Sea" in 2020 tell the story.

However back in 1968 James sold designs like Hina, Tangaroa, Narai and Oro were very simple designs with low rigs, and tiny cabins. Many were built by inexperienced “wana be” sailors, and they did not always have the seamanship skills to sail the boats resulting in some disasters. However, many of the builders were able to achieve long ocean voyages all around the World.

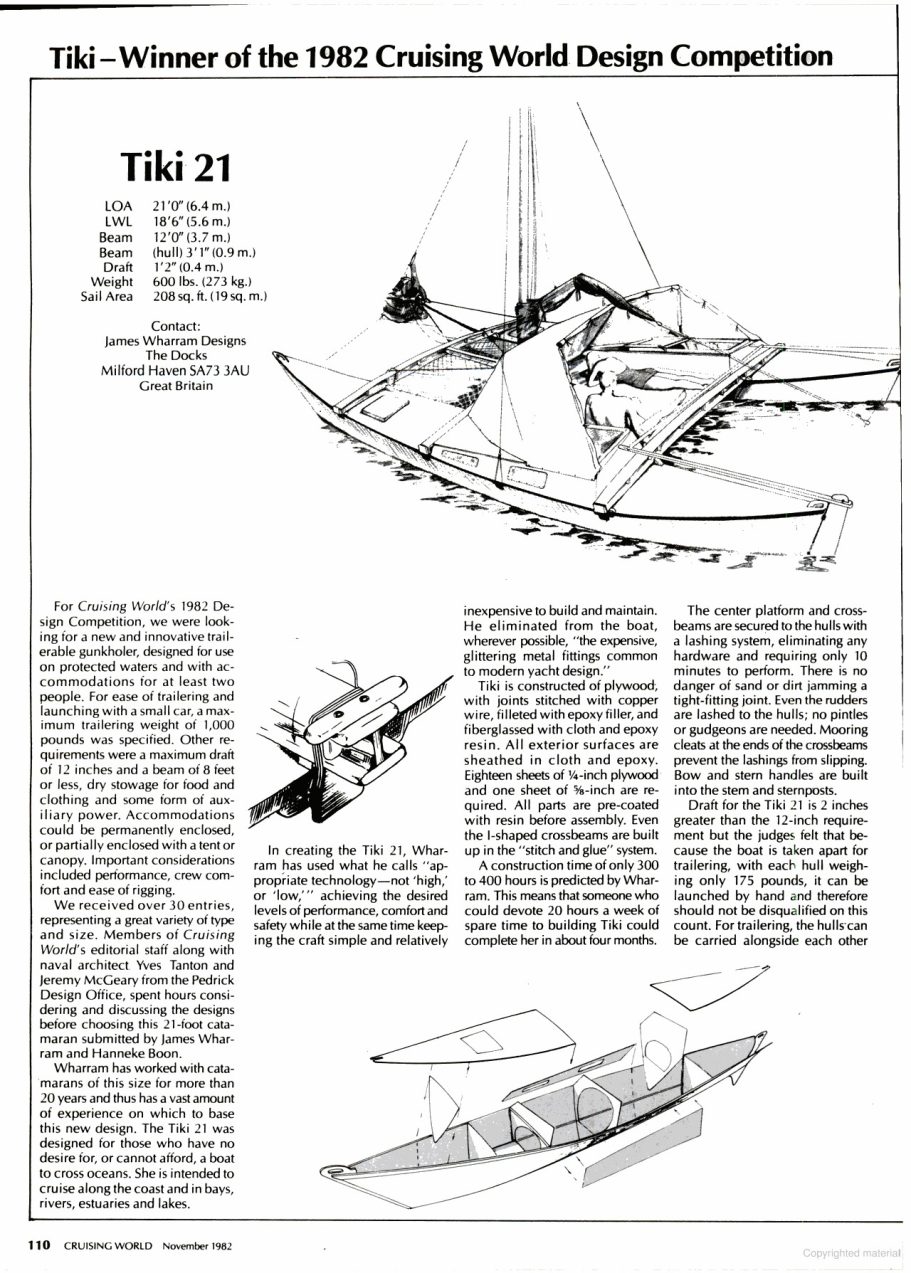

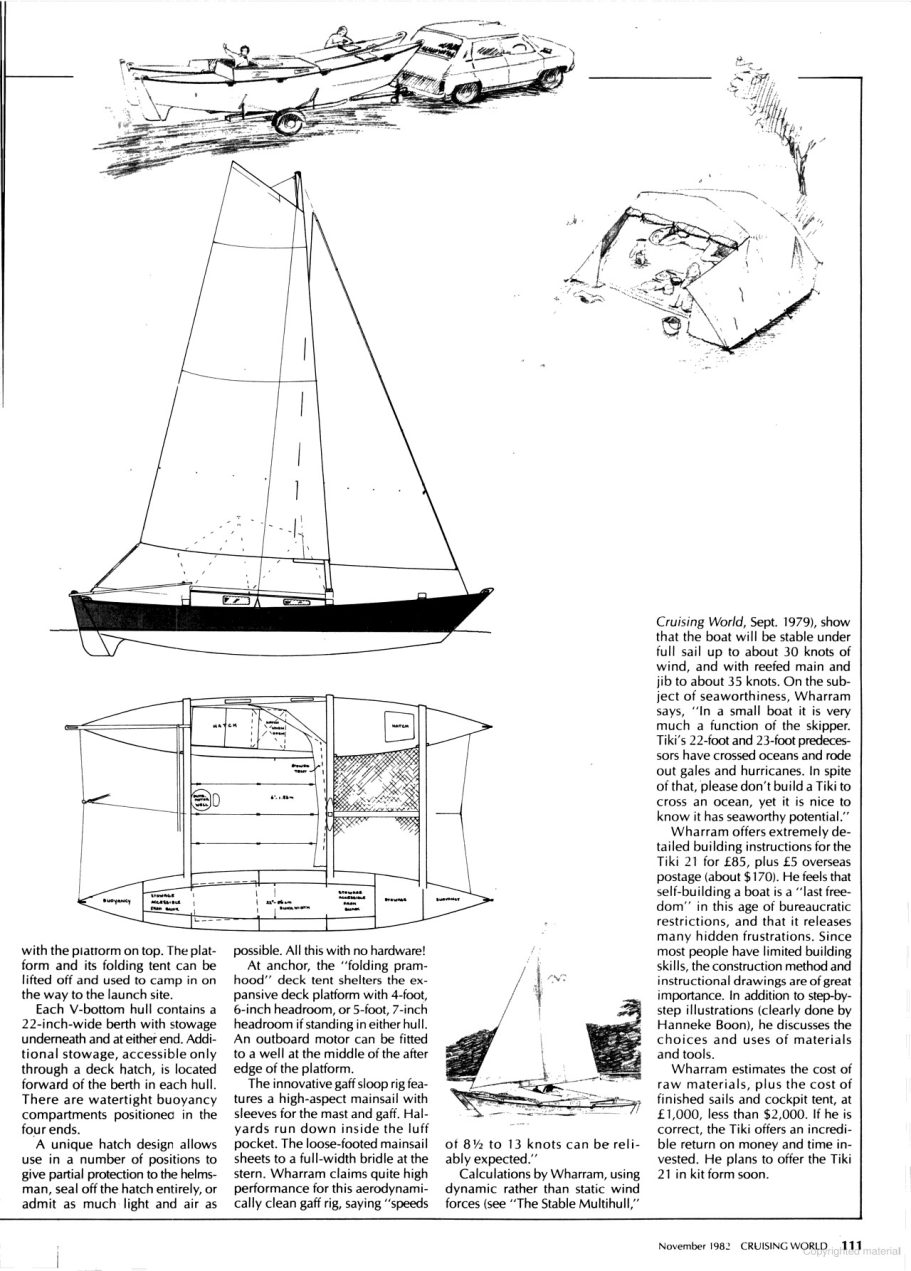

James moved to Cornwall for the last 40 years of his life and designed a range of small day sailing catamarans starting with the Tiki 21 in 1982. He marketed them as car trailable to be able to give people holiday escapes and weekend sailing. They were for people who did not wholly reject land-based lives with jobs. He designing the Tiki 26, and Tik 30, and started producing the Tiki 28 and 36 from his boatbuilding business in Cornwall in the 1990's.

The Wharram tenets of flexibly connected hulls, low multi masted (most were ketches or schooners) and often gaff rigged or at times junk rigged or using a version of a Polynesian sprit sail (and in his earlier designs using the spritsail itself). The lightweight Tiki 21 and 26 models were both capsized in the hands of crews that did not appreciate that they had limits; this is true of most multihulls that inexperienced sailors or contrarily experienced mono hull sailors fail to detect that they are on their stability limit because they do not heel over.

Wharram never changed his opinion that multihulls had to be sold as safe family boats and freedom from capsize was an essential starting point of his marketing.

He was very critical of designs that could capsize easily because they were over canvassed, but the reality was that his designs could capsize too especially when the owners or builders enlarged their rigs from those designed and added centreboards or dagger boards or other keels to improve speed and windward performance.

He always claimed that his designs were free from capsize indeed his Design Book still appears to make this claim and it is often repeated by Wharram enthusiasts. But it is not entirely true!

James blamed the capsizes of his later Tiki 21 and 26 designs on his competitors saying he had to design lighter faster boats to be competitive and older versions (Hina 22, Hinamoa 23 and Tane 27) did not capsize. However a man in Burnham on Crouch in Essex fitted a bigger to a 22 foot Hina and sailed it in very rough weather to France. He was enthusiastic about the design but capsized it in sheltered waters.

The story is online*:

" 'Twinstar’ was a James Wharram 22’ Hina catamaran. She was designed for fast coastal and estuary cruising with a crew of two. The original Bermudan sloop sail plan showed a box mast constructed with plywood supported by an internal framework. After the mast was shattered when I was racing the catamaran, I replaced it with a Bowman kit metal spar. Likewise I exchanged the wooden boom for a metal one. Instead of using lanyards to set up the rig I fitted bottle screws. Back in the 70s James Wharram preferred the use of low-tech materials that could be found locally; this philosophy came about as a result of his study of native Polynesian multihulls. Therefore the wisdom of me ignoring his rigging plan for the Hina was open to question. In 1972 when I owned ‘Twinstar’, I didn’t give it a thought. I believed I was right, and that the boat would perform better, particularly to windward. I had not appreciated the inbuilt flexibility of the original rig. I was always looking for adventure, therefore I cruised my Hina from Burnham-on-Crouch to Calais and Boulogne. I remember one hair-raising moment when I was rounding Cap Gris Nez. The wind was about force 6, and breaking waves covered the whole boat, including my trusty Seagull outboard motor! I’m convinced the weight of the water trapped on the decks between the raised bulwarks stabilized the vessel, making her less likely to capsize. The fact that she was fully loaded with cruising gear could also have played a part, but the situation was entirely different when I raced her a few weeks later on the River Crouch. I stripped her of unnecessary gear to make her light for the race, but that may have been my undoing, because she turned turtle during a squall. The story is best told by the following excerpt taken from an article written by me for one of the Up River Yacht Club’s quarterly bulletins. "Once clear of the Fambridge trots we settled down to what we thought would be a hard beat in a steady force 3, but by the eight knot buoy it all happened. She was on the starboard tack, lee-bowing the fast-flowing ebb, when the fatal coup de grace occurred. A very strong squall hit us fair and square on the beam as the sails were pinned in tightly for windward sailing. We had no time to ease the sheets, and she was over in a flash! Well, in fact the flip took about 2 to 3 seconds.

“I was sat to leeward, so that I was gently tipped into the cold water, but my brother on the windward hull flew over my head and he was unceremoniously thrown into the water. A sense of self-preservation soon had me sat on the upturned hull from where I anxiously scanned the surface for signs of my brother. Moments passed and I was just contemplating diving in to look for him, when he bobbed up, complete with specs in place and his woollen hat perched on the top of his head. Thereupon he started swimming around the boat in an effort to retrieve paddles, hatches, cushions and other bits and pieces that had been jettisoned. I persuaded him that his life was more important than saving flotsam and that he should immediately climb aboard the inverted catamaran.

Well, ‘Twinstar’ was not entirely inverted, because the mast was stuck in mud, so that one hull was raised from the water. Eventually we were rescued by members of the Club who thought it would be a good thing to do. I’m grateful they did, but by that time we were suffering from hypothermia. The following day at high water, with the help of the Fambridge boatman I managed to right the boat. The only damage she had sustained was a nick in the bulwark where a rope sliced into it when the launch hauled her upright.

Of the boats that I’ve owned, ‘Twinstar’ was the only multihull, but I must say I was impressed with her performance when reaching and running. There were times when she would achieve twelve knots on a broad reach. Advantages over a monohull with a deep keel were several: she could sail in shoal water, sail upright, had a very spacious deck and she could take the ground without fear of toppling over. Her disadvantages were: restricted accommodation, lack of headroom, wet in a seaway and her crew was exposed to the elements. Additionally, instead of one hull to maintain, she had two."

There was also a reported case in New Zealand that a Tane had a big rig designed by Grainger and that capsized in a squall too. Another Tane capsized because the lee hull filled with water and a Tiki 21 and a 26 and a Pahi 26 are all known to have capsized. Wharram catamarans have disappeared at sea too.

This is not to say that they are not seaworthy designs with a great record of many thousands of miles of cruising. The claim in the design book that however that a million deep sea miles were sailed by Wharram Designs without capsize may be a true statement but it does not mean no Wharram design has capsized as people may think.

James was clearly not a man to suffer fools gladly particularly when those fools were (in his mind) his competitors like Arthur Piver, Derek Kelsall, John Shuttleworth, Roger Simpson, Richard Woods and Ian Farrier and many others that he criticised for being "city men" and that he thought that many put speed over safety from capsize to sell their designs (in competition with his own).

In literature of the AYRS, the PCA and articles and letters he wrote to the yachting press in the 70's, and 80's he shines out as a very opinionated character who seemed to be determined to pitch himself against convention at every level in his designs, his personal life and his confrontational approach to the establishment and yachting scene in general.

James dismissed the arguments by Kelsall and Shuttleworth that multihull development was to be found in test tanks and computer programs and that racing improved the designs. James preferred to look to principles he derived from study of the major book on Polynesian Canoes and his own empirical sailing experience with the pioneering Atlantic voyages for all the answers.

Relying upon his own experience and voyages he claimed to know what made multihulls seaworthy because of his sailing - a view which of course did not give credit to the experience and ocean voyaging of other designers particularly Piver, Kelsall, Newick, Crowther and Shuttleworth all of whom had a great deal of sailing experience, and had also done trans-Atlantic's and had other sailing experience that distinguished them as men whose designs reflected their own views gained in learning how to sail a multihull in a range of conditions.

James always established his credentials based on talking about his Atlantic crossings and his "sales pitch" implied he had more Ocean experience than others. His 1986 "design book" sets out his history in away that suggests that some other designers (I think he was aiming at Roger Simpson and Richard Woods in particular) were copying him and failing to improve on his work.

However James was not the only experienced sailor designing multihulls. For example in 1966 Derek Kelsall had not only crossed the Atlantic in a multihull three times (compared to James' four at that time) but also won the 2000 mile RBR; arguably a race requiring exceptional skills of seamanship in the treacherous waters around the course.

Piver, Crowther, Newick, Choy, Patterson, Shuttleworth, Richard Woods, Roger and Andrew Simpson, Nigel Irens and many, many others who were building and designing multihulls in the 60's, 70's and 80's were also Ocean crossing sailors who navigated storms and learned a lot about the design and handling of multihulls that they incorporated in their own approach to design.

As with James' designs many pioneering successful Ocean voyages were made in other designers' multihulls in the 60's and 70's building the modern knowledgebase that supports multihull seamanship today.

Perhaps other experienced multihull designers chose to be more modest about their seagoing experience because they were also aware that multihull design was very much an evolving experimental process and that their "State of the Art" designs would be evolved and greatly improved in the future and they knew that they were at the Dawn of a new age in terms of developing multihulls.

Pat Patterson for example was famous for his bestselling Heavenly Twins family cruising catamarans, but he had sailed multihulls extensively in coastal waters and also achieved two circumnavigations and had several Atlantic crossings to his credit in his own designs. I met him and found a quiet man that was incredibly modest. This is both apparent in his book and in person.

Jeff Schionning is also a designer who is credited with 100,000 rough water miles sailing that forged the basis of his design work. His catamarans are very different from the Wharram concepts.

But throughout his long career James clung to the design principles he had established in the 50's of simple V shaped hulls, open slatted decks and canoe sterns with flexible beam connections and low aspect ration rigs. He argued against statements by Shuttleworth and Woods that racing would help to develop multihull design and practically suggested that the lessons had all been learned in the past and were represented by his designs.

He warned against the round bilge hulls, central bridge deck cabins and transom sterns common to most modern catamaran designs. Empirical evidence now shows that he was probably rather eccentric in his views albeit that he designed many safe and seaworthy boats.

But so did other designers who adopted the opposite opinions to James.

That said, James’ sales success, the number of boats built to his plans and above all the number of voyages made in his designs are his epitaph. Many people empathised with James' values and his political, philosophical and lifestyle ideas teamed with his devotion to Nature and learning lessons from Stone Age sailors to build boats that owed nothing to modern mainstream yacht design.

The early journals of the Polynesian Catamaran Association that James had created around his designs and the people that built and sailed them are available online and are an interesting read. They tell the story of how James gathered many aspiring catamaran sailors and builders to his designs. He had a vision of a great body of people all over the World sharing their experiences and building catamarans, voyaging and sharing the results. James believed that he was leading the biggest multihull user group in the World.

Sadly it did not quite work as he so inspirationally wrote. Some sailors of his designs lacked skills and experience. Unlike many designers he encouraged his early builders to be "creative" with the designs too which produced some odd interpretations of the plans -some more successful that others which caused breakups at worst and ugly aberrations of the designs.

The film about the building of Tehini (see link below)shows that the craft was rather roughly built with tar over the hulls and roofing felt and tar used on the decks -not something you would see at Camper & Nicolson! The strange triangular cabin tops made her look very homemade (in my opinion) and it seems that she was indeed built to a very tight budget using exterior grade rather than marine plywood. It is no surprise that the vessel was very short lived. Launched in 1969 she was deemed too rotten and unsafe to sail by 1985 and in about 1990 she was burned before James sailed off around the World on Spirit of Gaia.

Wharram's Rongo had been built in 1957 and was effectively a houseboat on a beach ten years later. In 1969 when he moved on to Tehini she too was rotten and James gave her away to the Sea Scouts to use as a shore base however they tried to take her to sea and she sank. But many builders assembled beautiful craft to his plans and the Wharrams' own Spirit of Gaia was built to professional standards in 1994 and sails in Portugal today under Hanneke's command. Her maintenance is chronicled on the Wharram website and the story demonstrates how a well built, high quality ply/epoxy vessel can succeed and achieve longevity.

The PCA eventually came a stage where it was not functioning well and there was a big disagreement between James and the association because of its committee starting to align with other Multihull Interest groups and other designers.

After the collapse of "James Wharram Associates" in Ireland James, Ruth and Hanneke went back to Cornwall and had to start out again to rebuild their lives and the design business. By the time he wrote his final book in 2020 he or Hanneke who co-wrote it, was able to see where a lot of the blame lay in James himself and the breakup was a consequence of his arrogance. Yet also it is clear that behind his conceit he had a deep desire to win the credibility and recognition of the yachting establishment and it was his mistaken belief that taking part in the Round Britain Race courting publicity (in 1966, 70, 74 and 78) would give him that. It certainly kept him in the public eye but did not really enhance his reputation.

One press story in 1970 reported that he was walking round the docks hand in hand with Maggie while others were frantically working on the yacht!

It was reported that Tehini crossed the start line at 2 knots in last place and she finished last but one at the first stop over in Ireland. She started the next leg but retired immediately and went home while the rest of the fleet battled on in gales. The famous yachting correspondent Jack Knights questioned just how seaworthy the great Ocean sailor's Tehini was if it could not beat to windward in a gale (the reason James gave for retirement from the 1970 RBR). In the context of James' bullish article in Yachting Monthly and similar magazines describing the superiority of Tehini over "yacht" catamarans this was quite unfortunate. I suspect James saw such criticism as the "establishment" having a go at him because of his Northern background and unconventional approach but objectively he had exposed himself to ridicule on the one hand writing of the seaworthiness of his ocean going designs and his Atlantic voyages but on the other demonstrating the shortcomings of the Wharram designs. The disastrous trimaran in 1966; Tehini would not go to windward with her junk rig in 1970 and abandoned the race again on the first stage; in 1978 Maggie Oliver one of his closest female companions sailed her with his friend Bob Evans and again retired early from the race.

The reason for retirement was at the time said to be blown out sails; the 2020 book revealed the truth 40 years later that that Tehini had suffered structural failure of the main beams. No wonder they kept that quiet given the marketing of Wharram designs as having "revolutionised" boat building. Also in 1978 a grp foam sandwich Tane Nui started to fall apart with major structural problems (blamed by James on the professional builders poor work, not his design) and the 35 foot Pahi prototype proved wet and exposed. In fact her crew had a very wet uncomfortable race and in spite of some great speeds finished well down the fleet.

My analysis is that racing was an anathema to Wharram's designs and most of the people that built them and sailed them. Most owners either accepted the lack of luxury and high performance and loved the boats because they were so different to others. It was part of the appeal that these were not racing boats beloved of associations and yacht clubs and the "establishment". Wharram's owed nothing to fashion, or trends or ratings. Serious racing sailors were simply not going to go to James for their designs.

It is interesting that writing about Tehini's retirement from the 1970 RBR James explained that he was doing 14 knots and the problem was that when he reduced sail the Junk rig would then not sail to windward and that he wanted to sail at a "workmanlike" 6 knots rather than 14!

This suggests to me that he simply was simply not a racer at all as no one racing a boat would rather do 6 knots than 14. Racers are very competitive by nature and sail boats often to destruction. As we now see the racing multihulls are not cruising yachts but racing machines that are sailed on the edge. In racing the last knot of speed must be extracted from the boat. Many are raced recklessly and capsize or lose sails and masts.

However lots of sailors did not want to race or have anything to do with the yacht clubs that organise racing and were attracted to his designs because they were simple. easy to build and thus easy to repair and not "high tech" lacking the winches and expensive equipment that racing yachts have. You could make your own sails, use grown wooden poles for masts or laminate them or just buy metal extrusions rather than go to expensive yacht mast makers. The later Wharram wingsails have a zipped sleeve that attaches the sail around the mast so you do not need mast tracks and all the expensive fittings that go with them.

The cost of your whole Wharram catamaran might be less than the mast, sails and equipment of a high tech yacht from other multihull designers and it is this and the fact they were a combination of prehistoric design principles and old tech trad-boat technology that attracts people to buy or build a Wharram design. The rigs incorporate lots of pulleys and blocks to minimise load and the sails are boomless.

Wharram's designs are for cruising sailors not racers.

Other designers were also influential in the home build market like Kelsall, Simpsons, Shuttleworth and Wharram's former protégé Richard Woods who had started up in competition (as James saw it) marketing their own range of self-build designs in plywood and in GRP foam sandwich. In fact the market for all designs were different and Wharram's appealed to people who were not after luxury or high performance sailing and all the associated costs that came to achieve that.

That is not to say that Wharram designs like the Tiki's are not fast boats if well built and sailed skilfully but this is not high performance in the established sense.

The PCA was revived in 1982 as James and Hanneke took over editing the magazine "Sea People" before they encouraged more like minded people to take over but certainly for a few years the strong influence of James in the magazine was apparent and articles published followed the views that James had on boats, the interaction of people and Dolphins and water birth (yes his son with Hanneke) and it was apparent that James and Hanneke and their young son were enjoying a great life together while Ruth co parented and kept the Worldwide group of Wharram friends focussed. The magazines are still available on a website: http://pca.colegarner.com/sea.people.html.

Well worth reading to understand the Wharram phenomenon and the character of the man.

James became very busy throughout the 1980's and 90's both designing, running his own professional boatbuilding business, building his 63 foot flagship "Spirit of Gaia" and sailing her around the World in stages, while also developing new building methods using epoxy ply sandwich construction, and the Tiki range of designs which were much more sophisticated than his older designs.

The original designs are now referred to as "classic designs" by James and Hanneke. Most are still available in plan form. However it has to be said that they were often reported to be rather poor to sail, slow due to the high wetted area, prone to pitching because of the hull shapes, very wet due to waves washing up through the open slatted decks, as well as spray; not always easy to tack or manoeuvre, very basic and uncomfortable in their accommodation and with open unprotected decks and no shelter for the crew.

Wharram's early wooden catamarans suffered extensively from rot due to what was with metal fittings and bolts being breeding points for water ingress and rot. The way the beams were bolted to the hulls and on later designs the way the beams sat in troughs created real traps to breed rot. Later designs particularly the Pahi range and later the Tiki 38 and 46 tried to address this recommending careful epoxy sealing of all the holes and using lashings to attach the beams to avoid the metal fittings and the bolts that allowed water in and led to rot.

By no means were they the only plywood multihulls to suffer rot because this type of construction especially back in the 70's before epoxy resin took over, is afflicted with rot when water ingress occurs. But also, the primitive low aspect ratio rigs and lack of keels meant that close winded sailing and powerful windward ability were never really attainable by Wharram catamarans.

The designs were very basic and James encouraged builders to find their own creativity in much of the detail this was not a great idea and many people's ideas resulted in craft that were ugly or unsafe. Not only did builders change the designs and fail to follow the plans but they often restyled the boat, expanded the accommodation to improve perceived comfort, changed the rig, built solid decks and cabins and new structures so much so that the resulting vessel was a long way from what the designer intended. Sometimes failure to build specified beams and fastenings resulted in boats that broke up because the fittings holding the beams to the hulls broke or even the beams themselves failed.

Also at least one older Wharram catamaran broke up at sea due to rotten beams. A well known UK yachting journalist Geoff Pack went voyaging in a 34 foot Tangaroa writing about their adventures and also writing a book about cruising and voyaging. Unfortunately the boat started to fall apart in mid Atlantic and they survived becaus ethey had enough sprae cordage on board to lash the beams to the hulls.

This could bring unwelcome publicity such as the well circulated pictures of a New Zealand Wharram breaking in two on its maiden voyage (see the photo section on this website) because it was badly built not to the plans and more recent head lines that a "Wharram Catamaran" broke up at sea when in truth the latter was not a Wharram design at all but a creation built using Pahi 42 plans extended to 50 feet. It had a vast bridge deck structure and unstayed rig. The whole thing was inadequately engineered causing its demise at no fault of the Wharram design at all.

Others built boats that they lacked the experience to sail and immediately piled the vessel up on a sand or rocks resulting in disaster or break up. However many very good sailors built fine craft from Wharram plans and achieved great things with them sailing all over the World. Rory Mc Dougal modified a Tiki 21 very successfully so much so that he sailed it around the World and successfully raced it across the Atlantic.

The PCA flourished and with the arrival of the Internet went online as well as publishing a magazine.

However James concluded that others in the PCA had started to build their online own brokerage and design business about the Sea People community of the PCA and also "improved" the designs creating their own rigidly monocoque versions some with the deck cabins he so loathed.

One of the officers elected to run the PCA because he was an experienced sailor and skipper of Wharram catamarans gave the Association a terrific web presence by creating a "World of Wharram Catamarans" website with lots of pages about the PCA but also he included his own business of a specialist Wharram catamaran brokerage (which he still runs to this day but entirely separate to the Wharram brand) and so James took action to protect his own business identity and his intellectual property rights to 'Wharram Catamarans' as a brand.

The basic issue was that having a voluntary association independent from James Wharram created a conflict between the interests of the Association and the opinions of its members and James' business interests, opinions and the intellectual property rights to his own brand and use of his name.

Wharram Catamarans were not an independent generic type of boats (like multihulls in general) -they were the creation of James and his business associates and lately the team of James and his two wives, Ruth and Hanneke.

The naïve and idealistic concept of an association of owners and builders of those designs building a data base of collective experience and collectively creating developments and improvements of those designs while it seemed an ideal dream the way James had promoted it in the 60's and 70's did not work once others were seeing the designs in a different way to the designer or worse still (from James' viewpoint) the members or officers of the PCA became interested in other multihull designs and concepts or working with other multihull organisations whose views were an anathema to James. For example in the late 80's and in the 90's MOCRA and others decided to promote a design class of Micro Multihulls for cruising and racing. They also wanted to try and set up ratings and new racing Rules for different multihulls. James was not in favour of the Micro Multihulls and other multihull organisations encouraging racing and design rules that he though prioritised racing speed over freedom from capsize and was a vehement critic of this development.

This dispute that then arose between James and his former friends in the PCA was very unpleasant and bitter on both sides and it effectively killed off the PCA as an organisation. What happened in my opinion was really a collision between the idealistic dreamer community concept that James had championed for so long and the hard reality of business and commercial rights. It was terrible that it all erupted in public although ultimately it became a business legal matter.