James Wharram

British Catamaran Pioneer 1928 to 2021

James Wharram (aka Jim and Jimmy to his friends) is also sometimes described as the father of the modern multihull but that is not entirely accurate because as we are seeing the World was full of people developing mould breaking revolutionary multihulls and very few of them owed anything at all to Wharram's designs which in their unique characteristics were always different from the mainstream of multihull design.

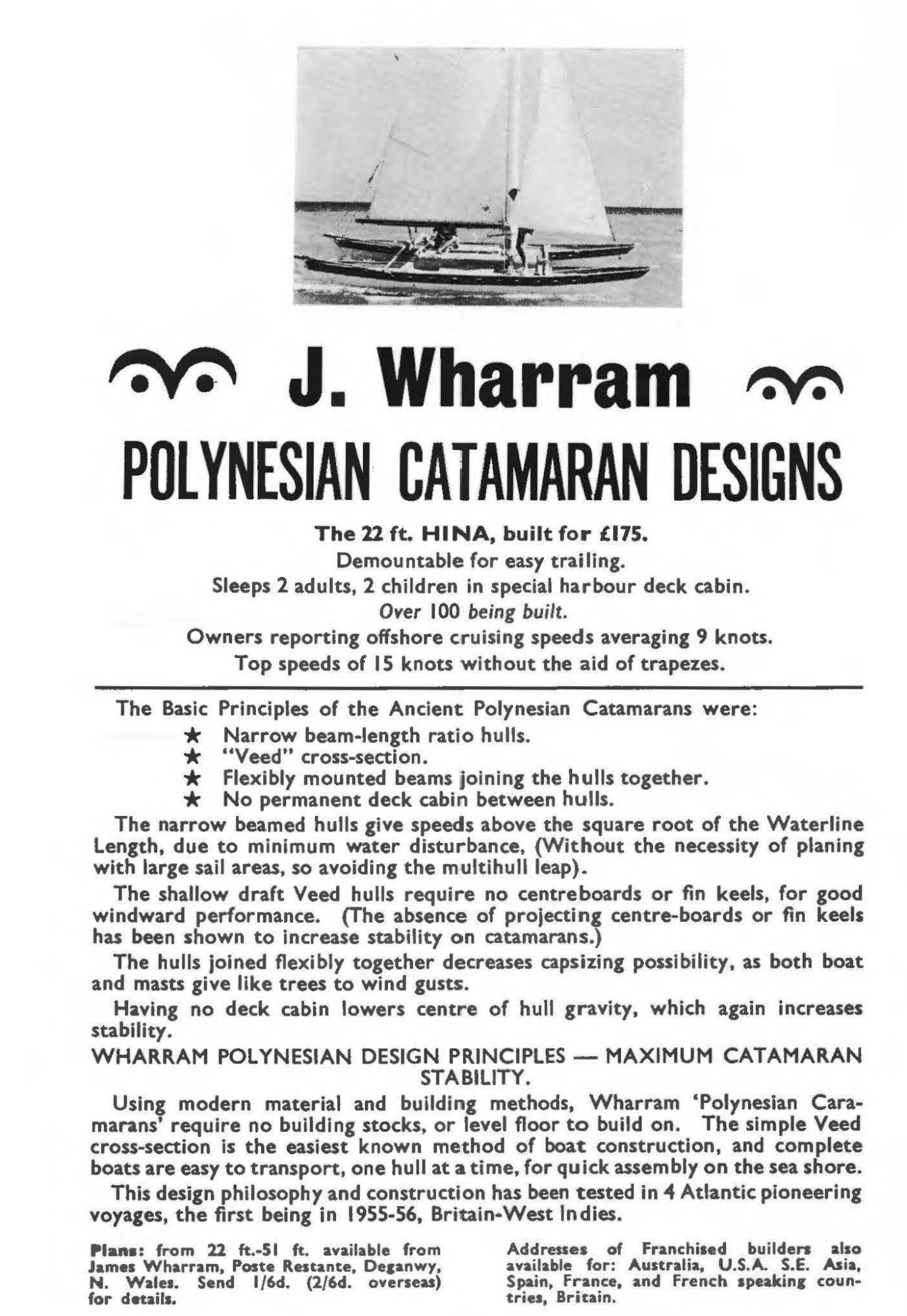

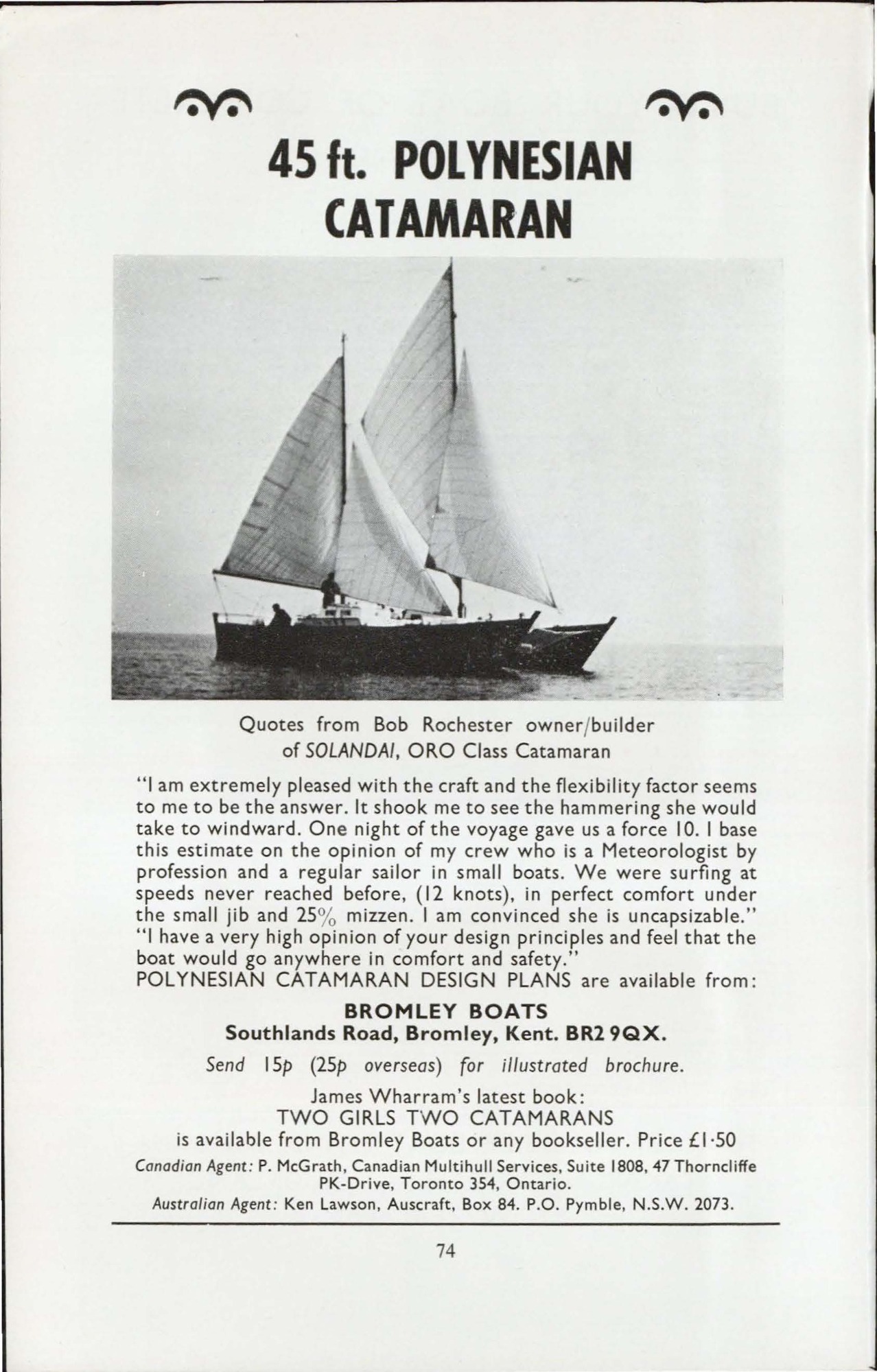

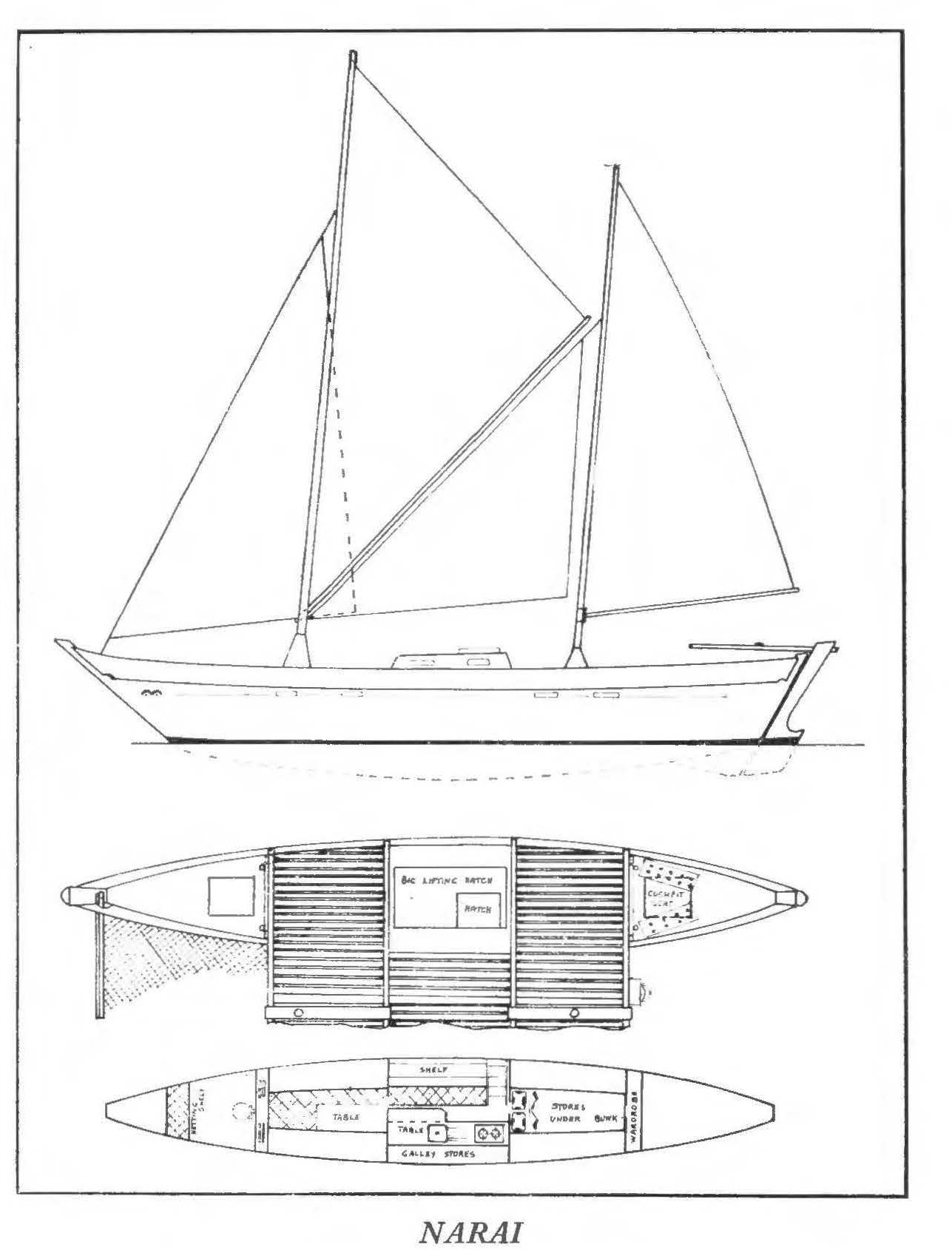

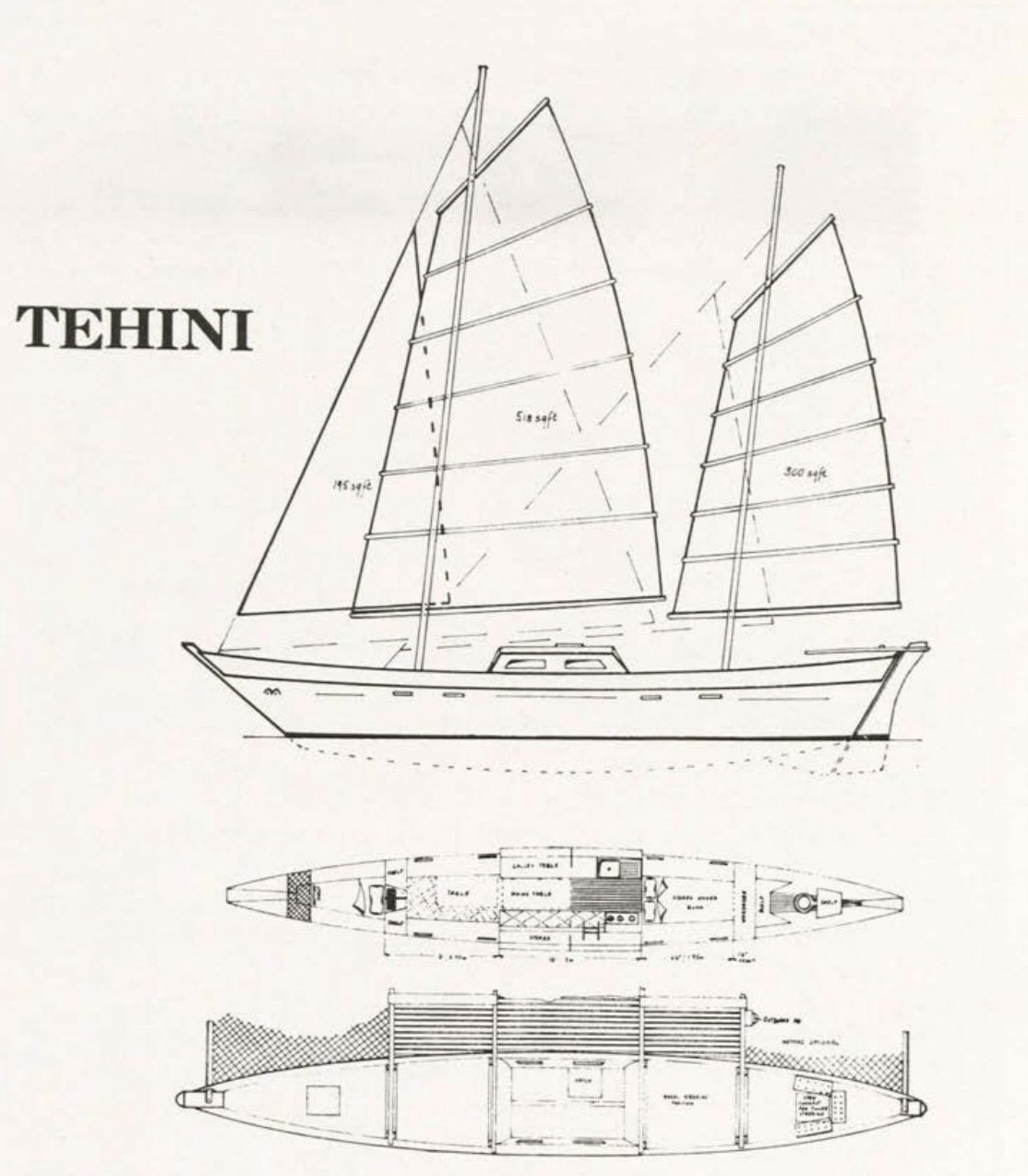

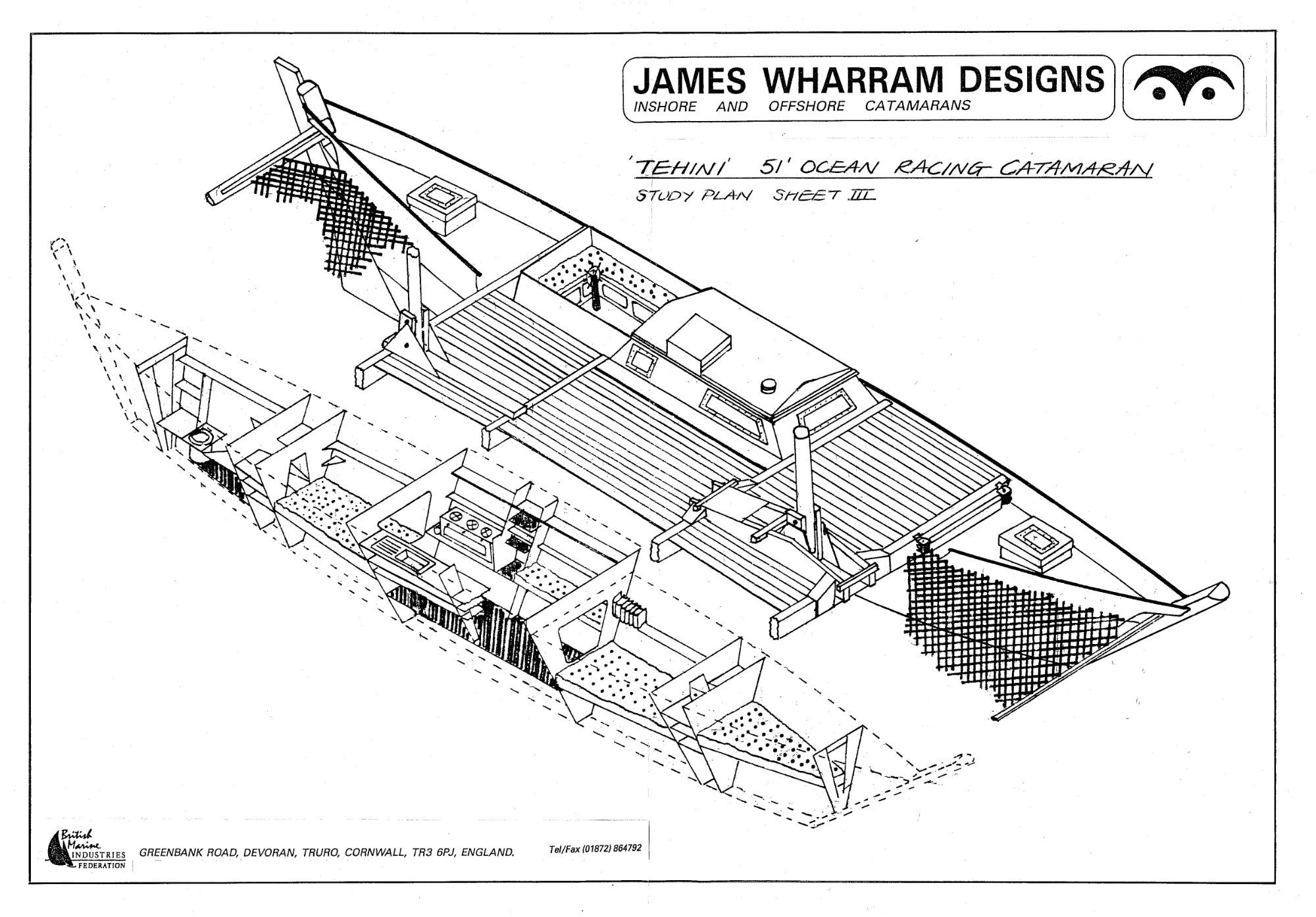

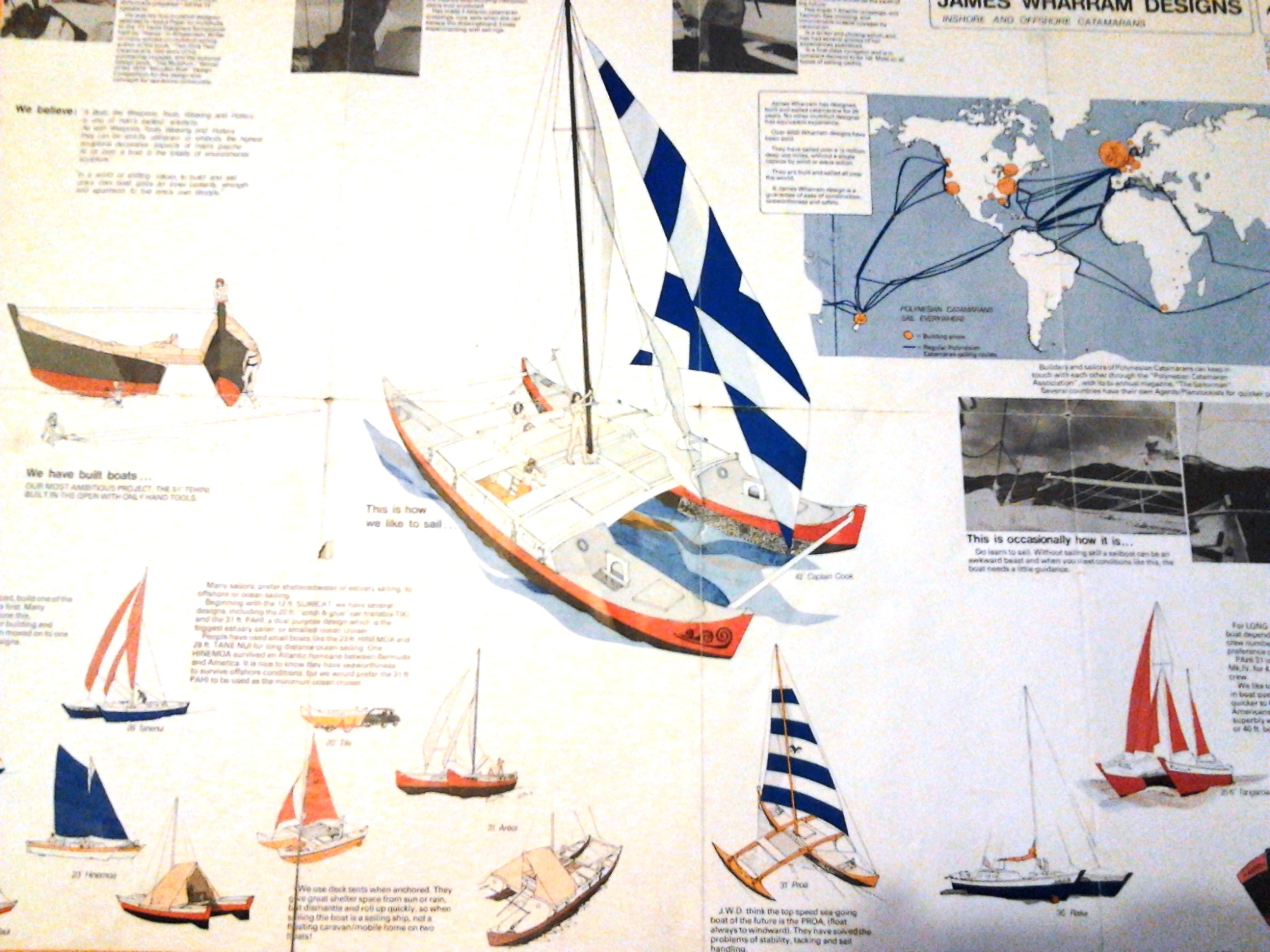

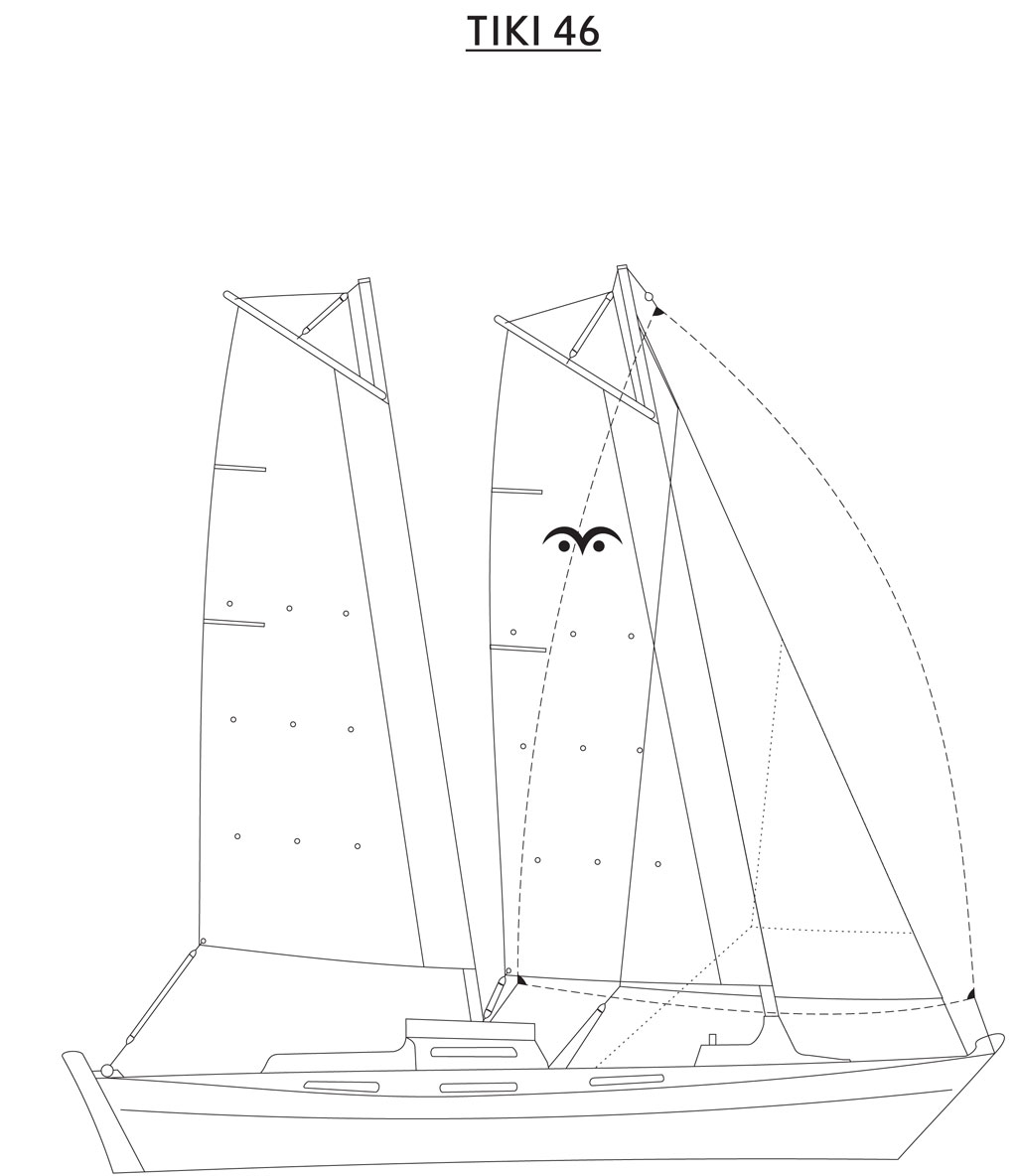

Indeed I would go so far as to say that the commercially successful multihulls that are dominant in the World today follow totally different design principles and styles to the Wharram designs which even today are unique albeit that Wharram claimed the distinction of selling more than 10,000 sets of catamaran plans for home construction. This is almost certainly more than any other home build multihull plans seller has achieved. Many of those plans are for the smaller day sailing designs and the Tiki 21 and 26 which were a big success after the former was launched in 1982. But in the late 60's and 70's many people built the 34 foot Tangaroa, 40 foot Narai, 46 foot Oro, and 51 foot Tehini that were all designed for ocean voyaging and very simple plywood construction.

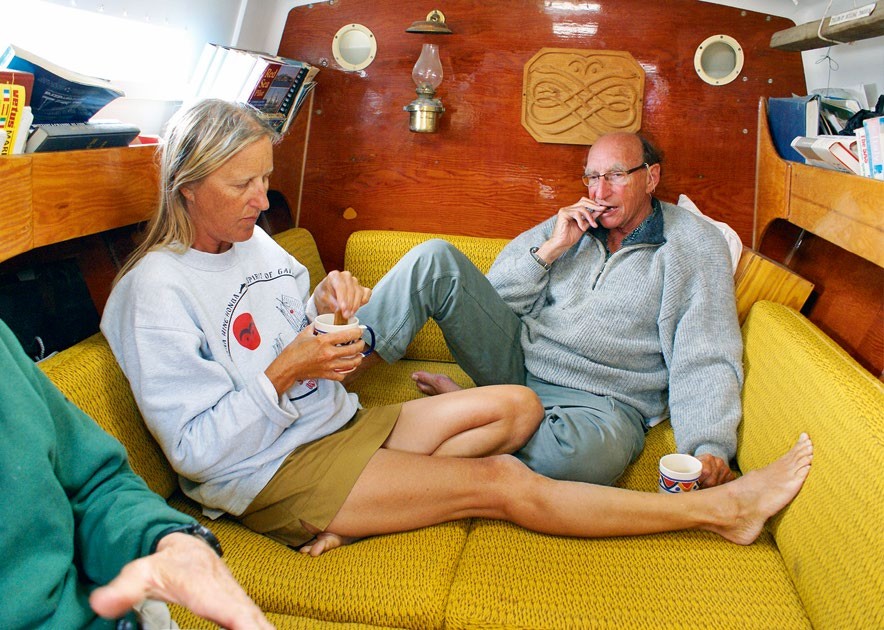

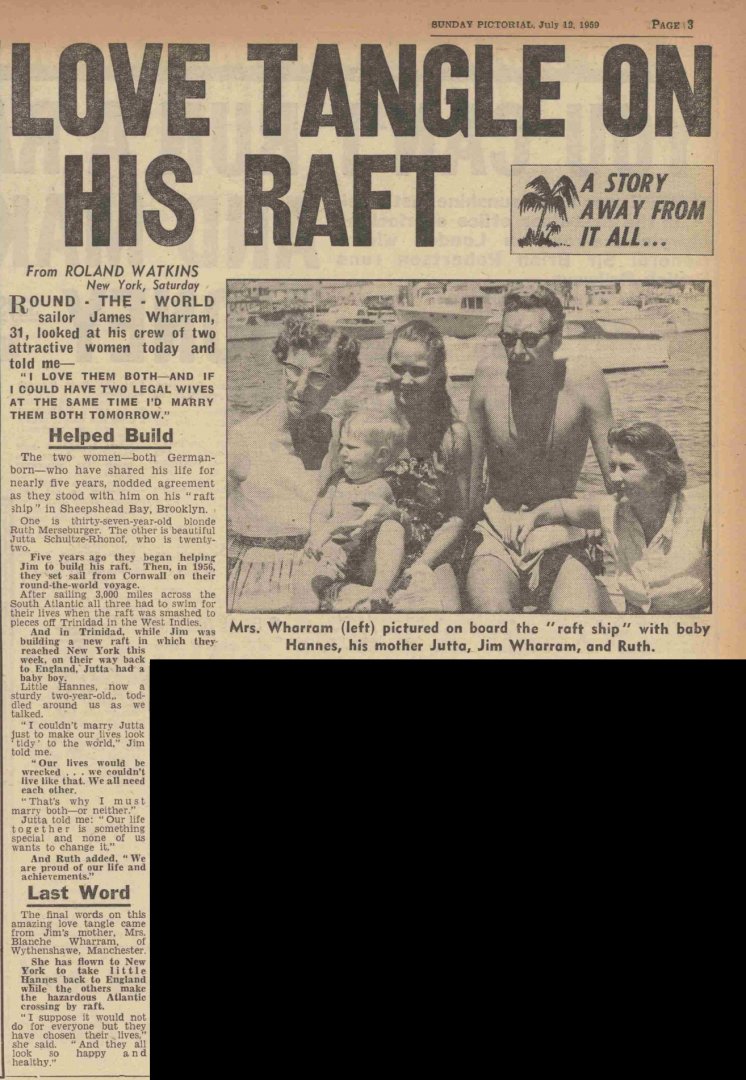

James and his wives Ruth and Hanneke built a terrific brand by being very different and always seeking to be controversial.

Some say that Wharram sold more than boat plans and his buyers instead bought into an entire philosophy rejecting "land" values of Western society.

Today Hanneke runs the business with their son Jamie, but such is the way the boating market has changed since the Wharram heydays of the 60's and 70's the market for self-build has declined. If you want to go cruising the second hand market is awash with used production boats.

A choice to buy Wharram plans to build your own boat is now more than ever a lifestyle choice based on sustainability and beliefs. Keen racers and those looking for high performance sailing will not choose a Wharram design, and it must be said that sophistication, and luxury do not apply to Wharram designs either. Anyone that chooses to build their own yacht now will do so because they have particular requirements -the desire to use the best modern design and materials that will not be present in older second hand designs and specialist interests and requirements. The self build market is rather more sophisticated now. The levels of technology and construction have moved on. That said particularly with smaller sizes there is no doubt still a market and great interest in Wharrams but the choice of designs is very wide with many other designers offering designs for self build.

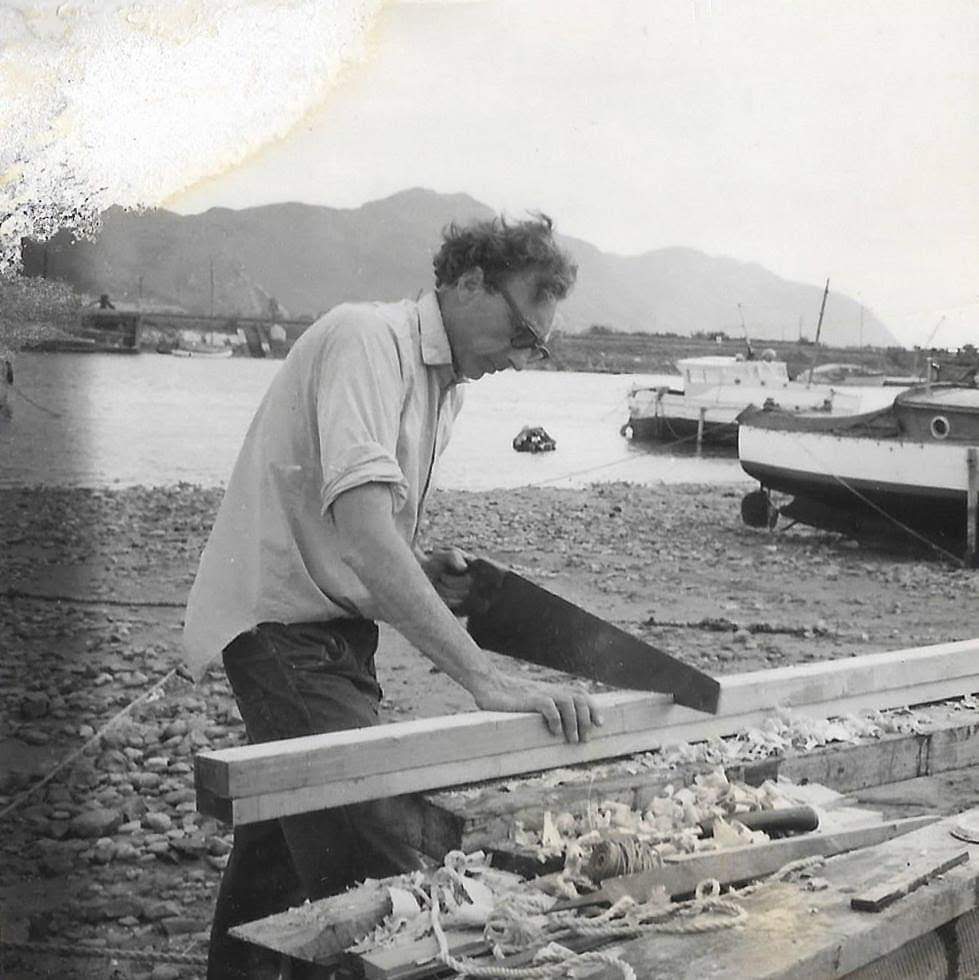

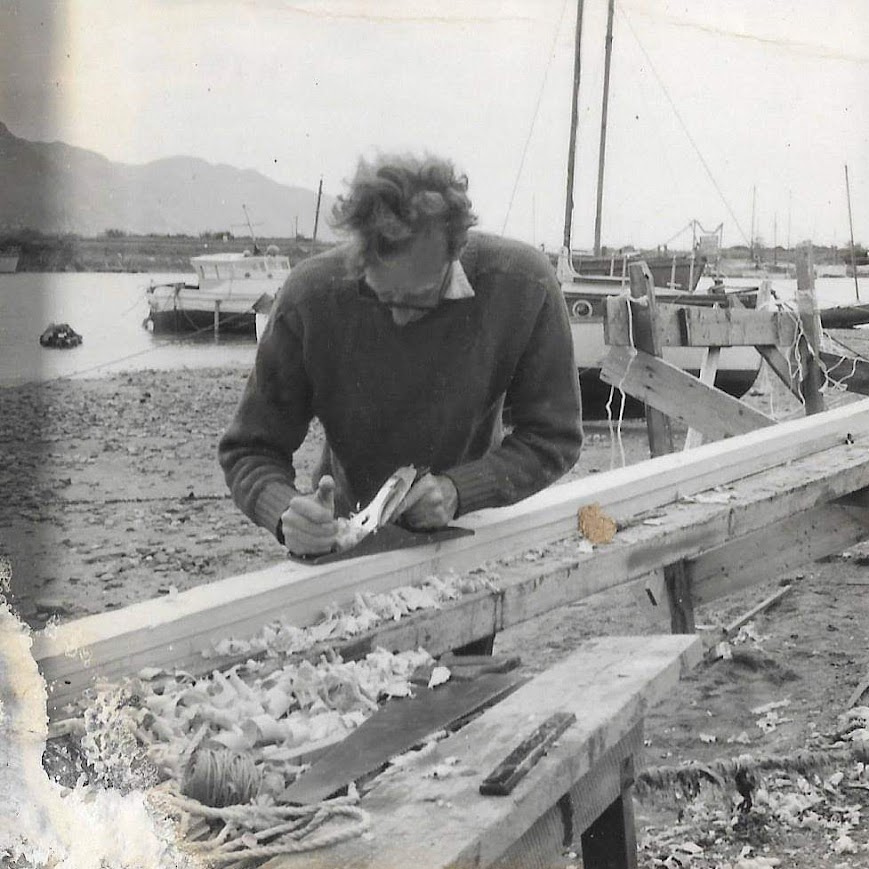

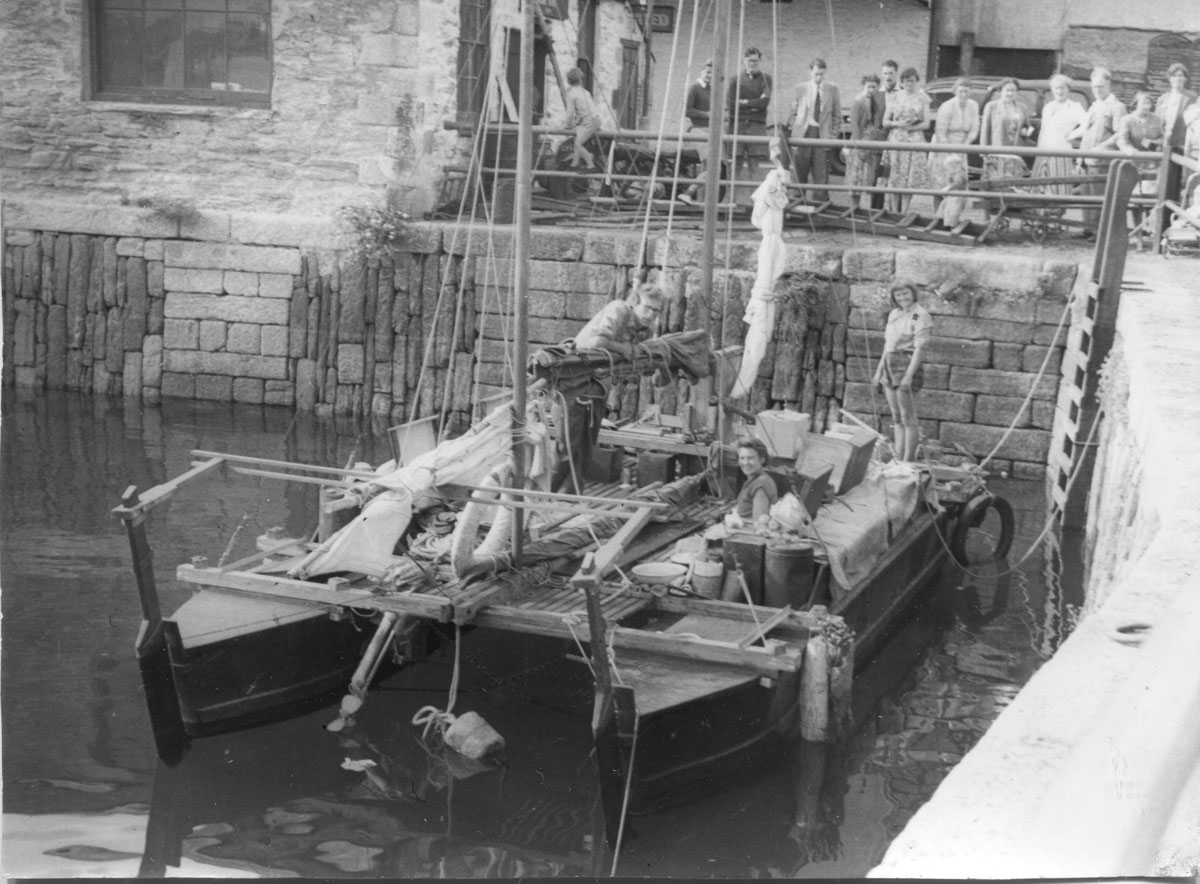

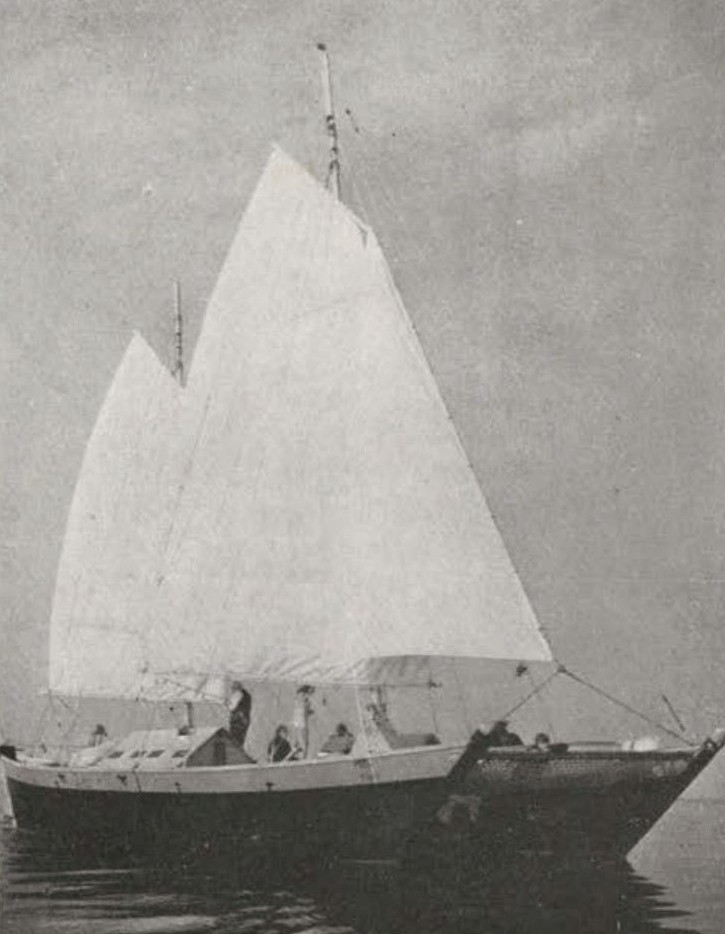

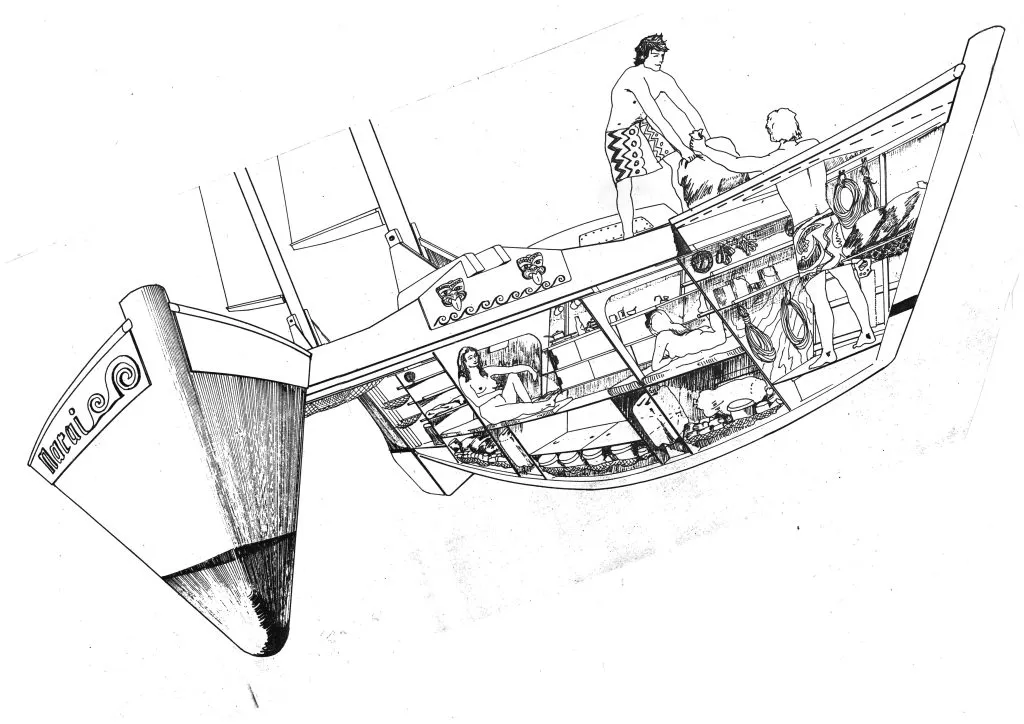

The first Wharram design was the 24-foot Tangaroa on which the three adventurers Jim, Ruth and Jutta sailed to the West Indies. Flat bottomed with a tiny rig and cabins like rabbit hutches and their voyage must rank as one of the bravest in the history of modern boating. James was a self styled Maritime Archaeologist. A Pathe News archive film at the time showed them before they departed from Falmouth in 1954. Conventional wisdom at that time was that the vessel would be smashed to pieces by the Atlantic waves and going to sea on it was simply suicidal. Conventional wisdom was wrong! They sailed to Spain, the Canaries and across the Atlantic to Trinidad. The catamaran soon succumbed to Teredo worm lacking antifoul and or copper plating below the waterline.

She was abandoned and the trio built a raft houseboat.

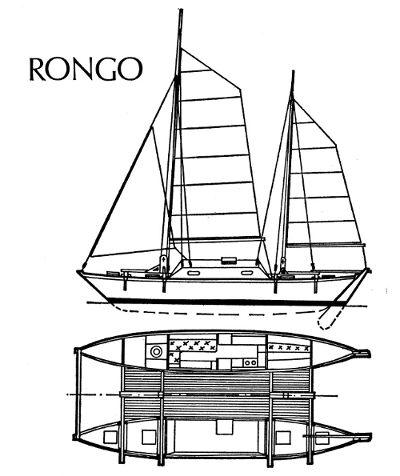

Living on the raft in Trinidad where Jutta had his baby, Wharram’s next project was to design the 40-foot Rongo.

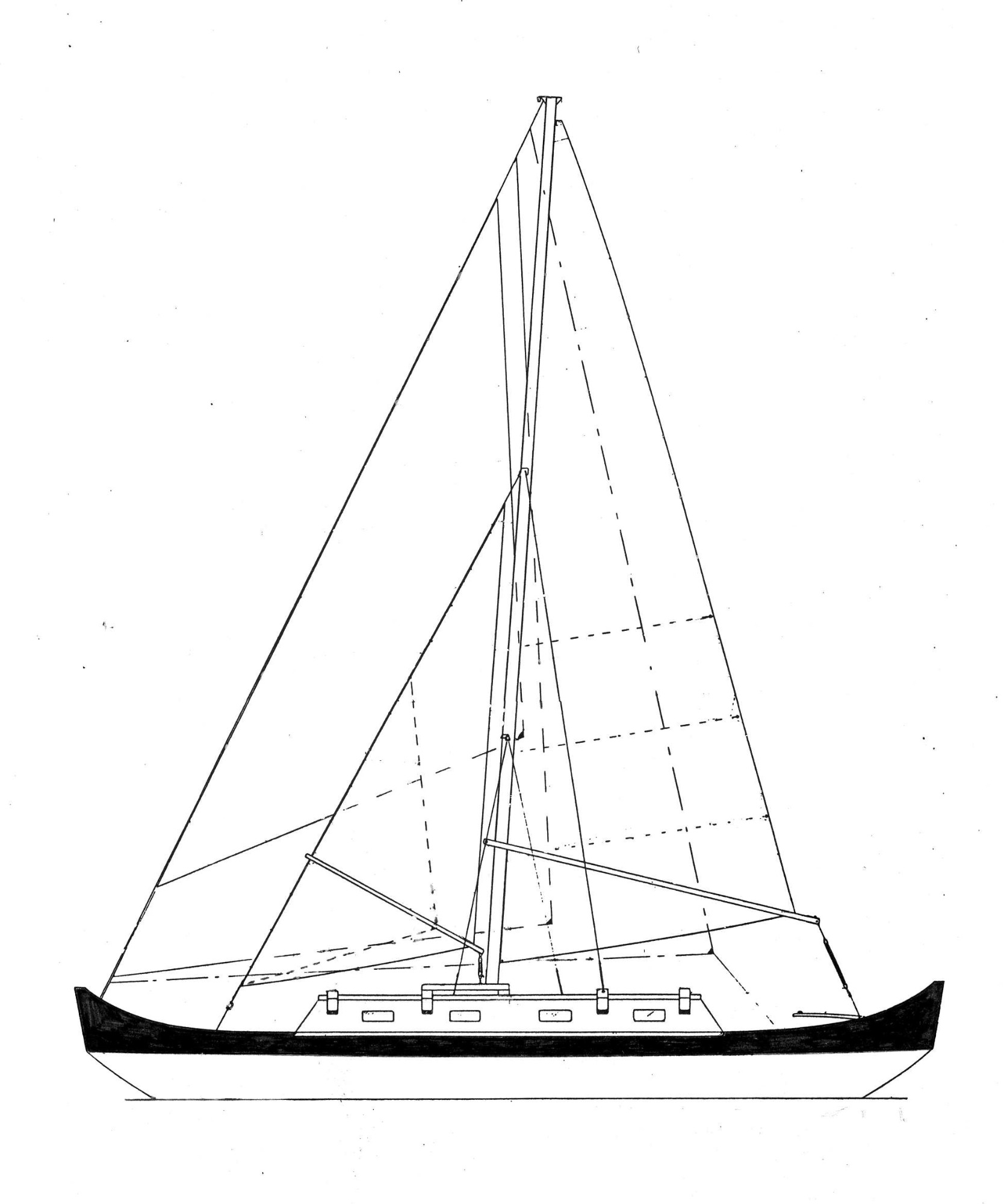

This brilliant design is without doubt the basis for every Wharram since and if you look at her and the later Tiki 34 and 46 (1990's) the family likeliness shines out although the construction methods are now more modern ply epoxy glass sandwich and the build method evolved to be suitable for home builders but so much more sophisticated and nuanced than the designs that Wharram marketed in the 60's.

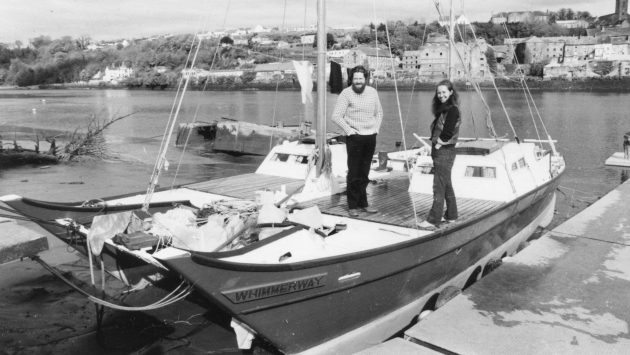

After a tough voyage from New York to Ireland in 1959 Rongo was readied for around the world voyage in Wales and then sailed to Ireland. James married Jutta in Ireland, and they all set out around the World. Jutta had already shown signs of developing mental illness -possibly related to trauma caused by her experiences in Germany during the War. Jutta’s death by suicide in Las Palmas ended the voyage and although Ruth and James still crossed the Atlantic to Trinidad they decided they could not go on without Jutta. They sailed back to Ireland and then Wales in 1962. They had now sailed Rongo three times across the Atlantic covering over 12000 miles in her.

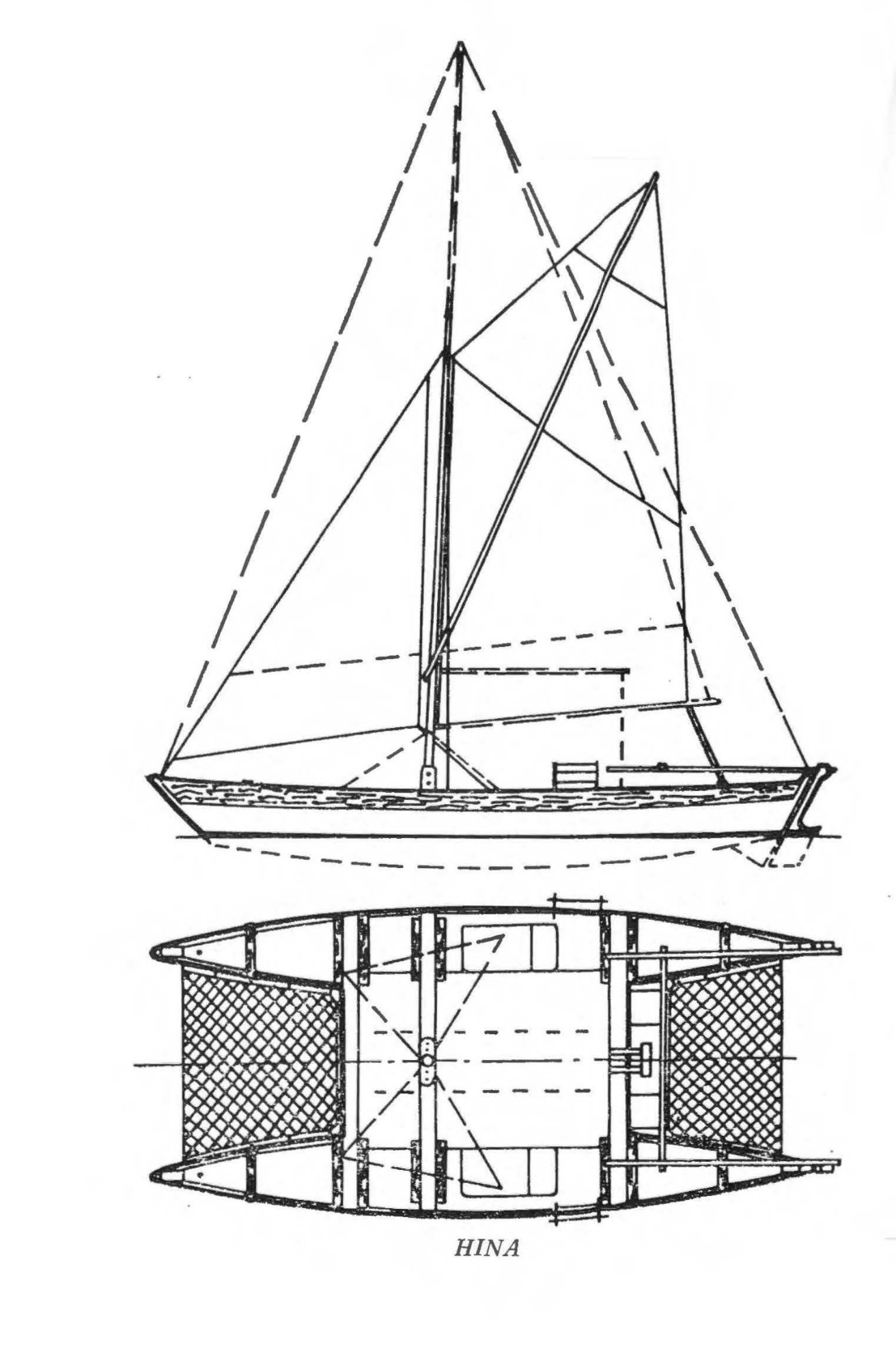

After his abandoned World voyage James and Ruth lived with James' son on Rongo on a beach in North Wales. It must have been a very hard life indeed in a cramped and spartan plywood catamaran without any modern facilities whatsoever. James had clearly suffered a mental breakdown himself and was deeply depressed in 1962. His dad encouraged him to design him a small catamaran which the two father and son then capsized on its first sail. But in 1964 James started to design again producing the 34 foot Tangaroa for a friend and this led him to start publishing a design brochure and advertising in Yachting Magazines. This was followed by a 22 foot Hina.

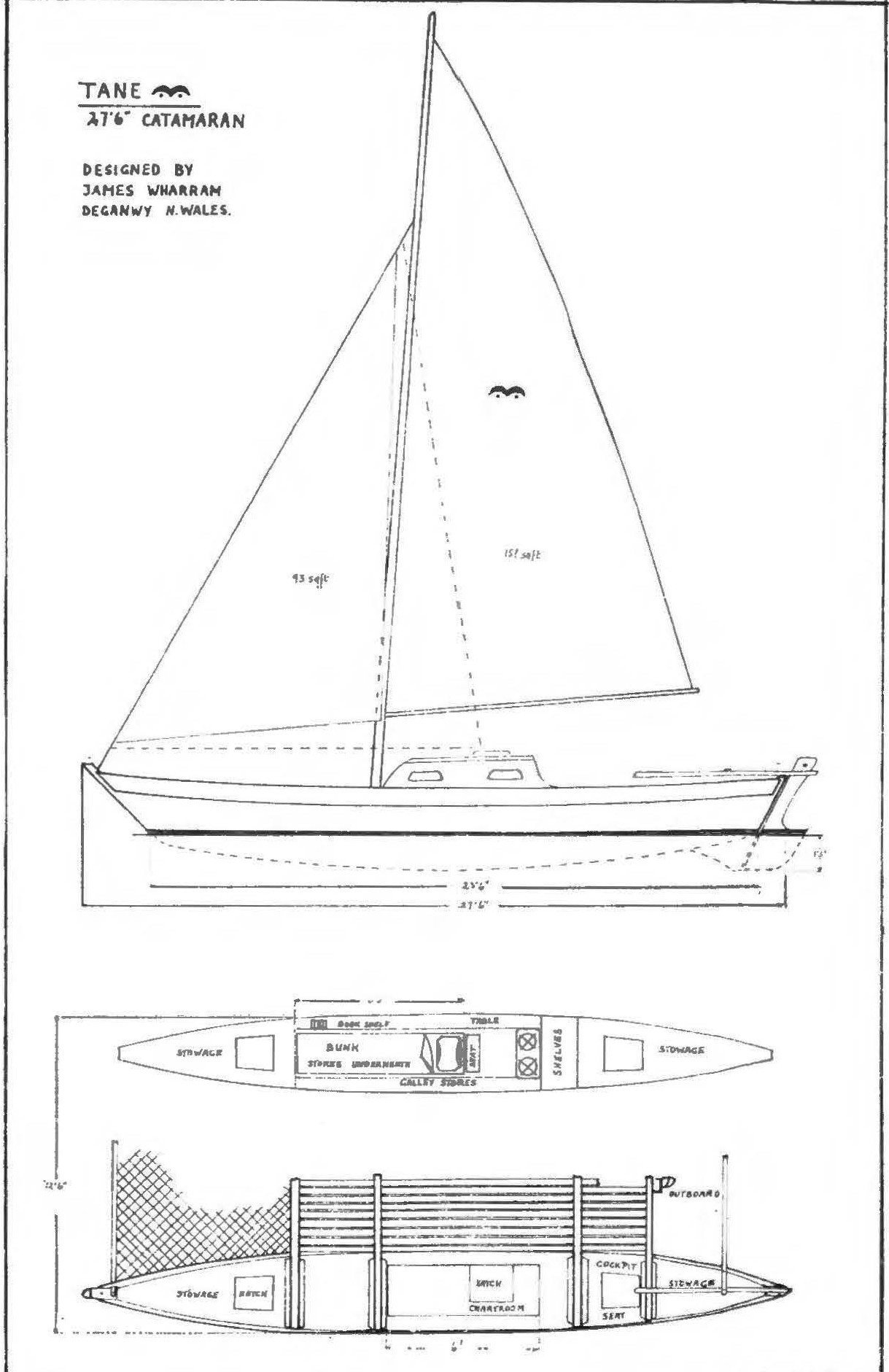

Both designs were really quite crude and simplistic with spritsail rigs that were not a concept that could achieve the high performance sought by most multihull designers. Some found them to be slow in stays or difficult to sail to windward at all. The rigs were not optimised for performance and the V shaped hull without any external keels or dagger or centre boards were poor performers up wind and indeed high wetted surface made them sluggish and often difficult to manoeuvre. However James had developed a simple building method so someone with no boatbuilding experience could build a catamaran.

If the builders had no sailing experience in well designed vessels that sailed well then perhaps they were not bothered by what other sailors would perceive as a poor performance and what was generally an unhandy vessel. The double ended V hulls (like those used by the CSK designs) were prone to pitching too. Combined with heavy wooden masts -usually a ketch or schooner rig, and owners stowing things in the stowage lockers placed at the ends of the hulls, these boats had some characteristics that were unattractive in reality. The use of slatted decks made the boats wet in any seas too and they lacked any real protection (as designed) for the crew. On Rongo James built cockpits behind the cabin tops with a canopy and he did a similar arrangement on Tehini. Smaller designs featured open decks and unprotected cockpits. Often you saw Wharram catamarans that had no protection and exposed steering positions on their bare and exposed decks open to the sea underneath and above by design.

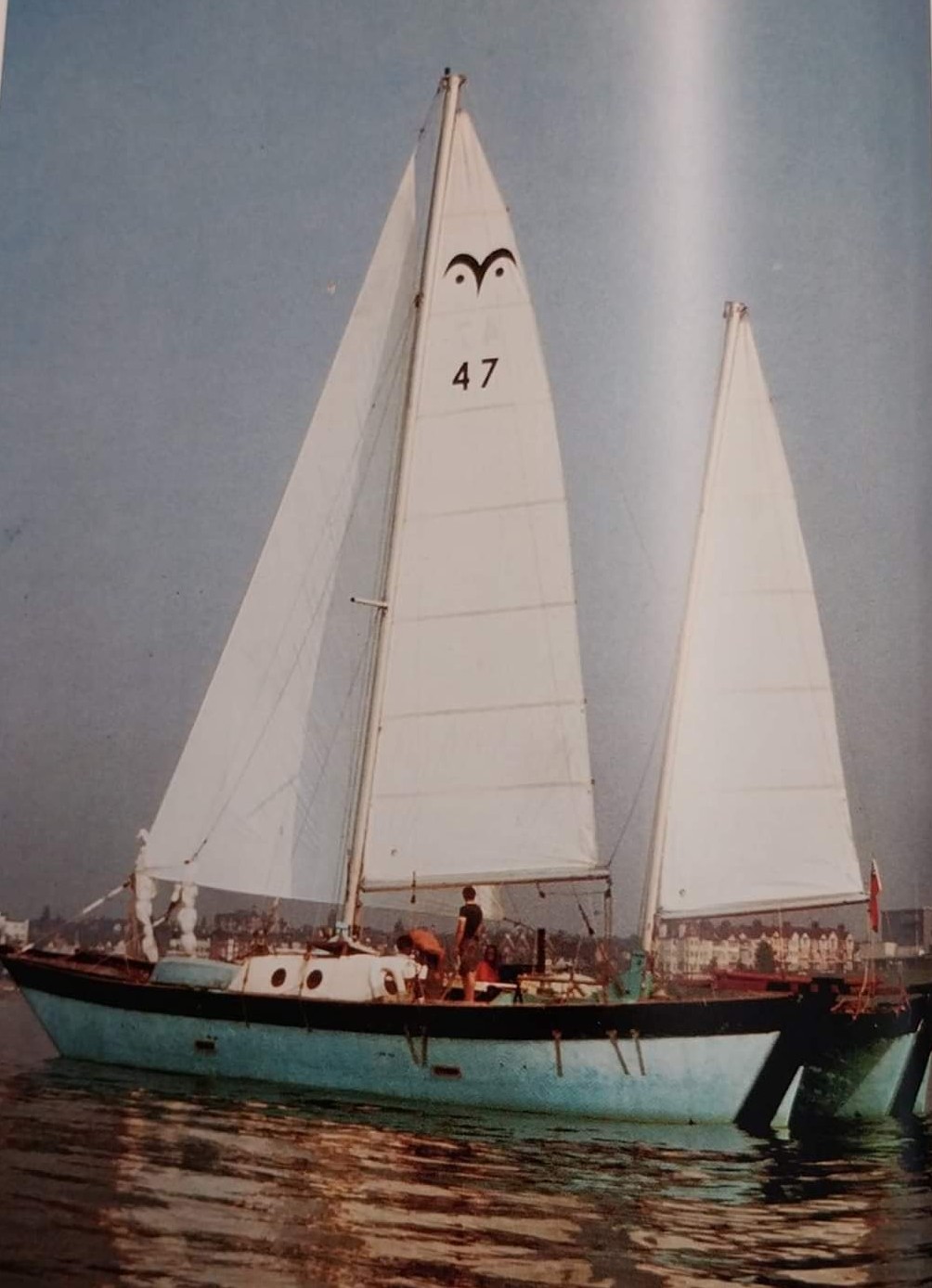

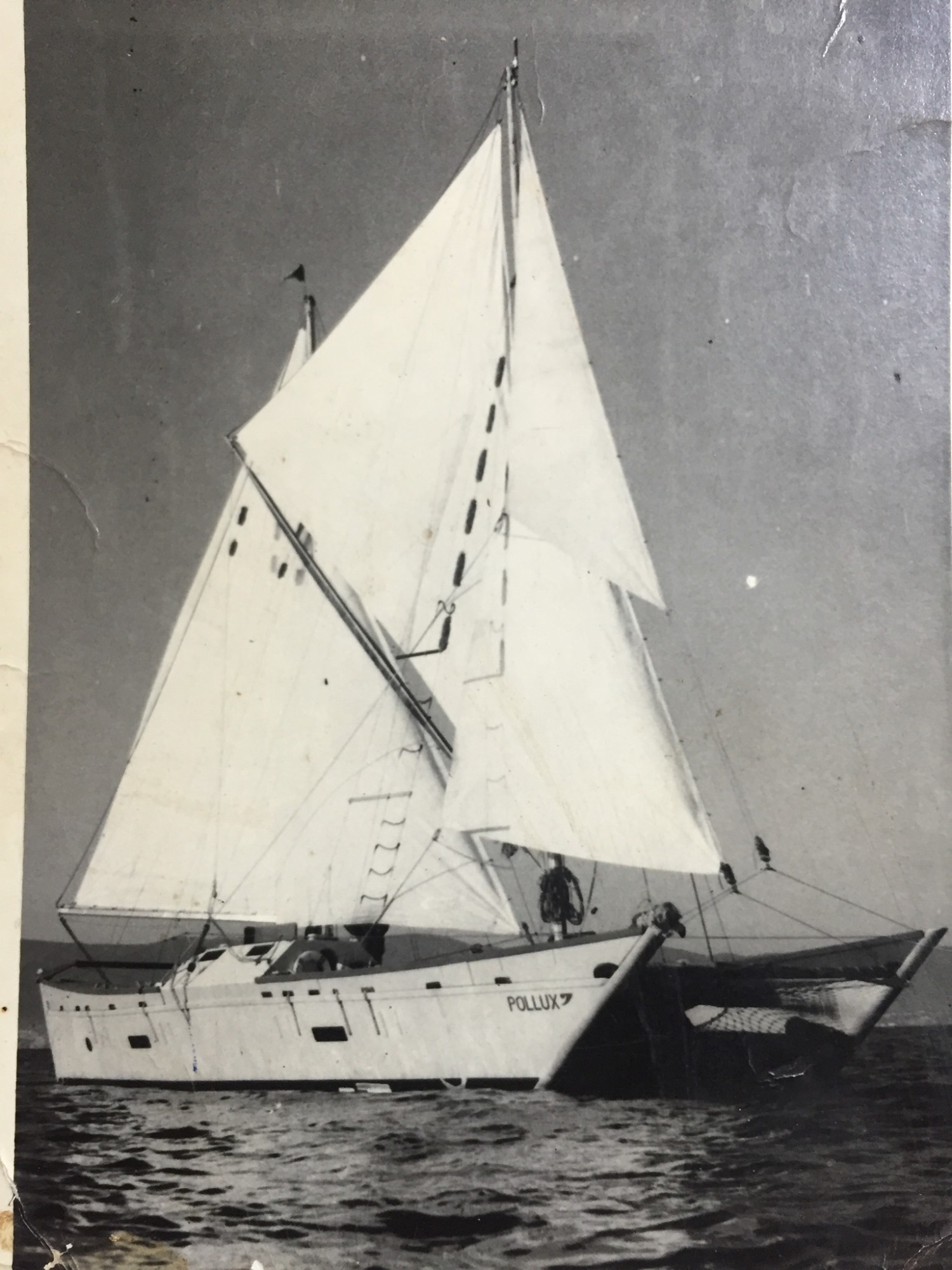

He followed this with the 46-foot Oro Ocean cruiser and replaced Rongo with the 40 foot Narai. Above the Hina he designed a 27 foot two berth ocean cruiser the Tane. He published articles in yachting magazines and his self-build design catalogue started to achieve sales and boats were built, and others sailed the Oceans in them. By 1968 when he designed and started to build his dream ship, the 52 foot Tehini James was established as a notable figure in the growing multihull scene in the UK and Worldwide. His boats were being built in astonishing numbers.

In 1965 James had built a trimaran called "Tiki Roa" and entered the 1966 Round Britain Race. Writing to AYRS and Multihull International, his ambitions for the double outrigger were frankly delusional - he was carried away by his ideas and thought it would be as fast as the sponsored 40 foot Mirrorcat entered by Rod McAlpine Downie and Kelsall's Toria. It's small spritsail ketch rig and V shaped hulls meant it was not going to succeed as a racer, and it had almost no accommodation either. A commentator in the press likened it to a fishing boat and noted how poorly it pointed compared with the relatively sophisticated yachts it was racing. The race was over quickly when the centreboard broke. Post race James abandoned the concept and indeed became very much against double outrigger trimarans as designed by Kelsall, Crowther and Newick in particular. However as Kelsall sarcastically told the audience at the 1975 Multihull Conference in Canada it established that James was definitely not a trimaran designer.

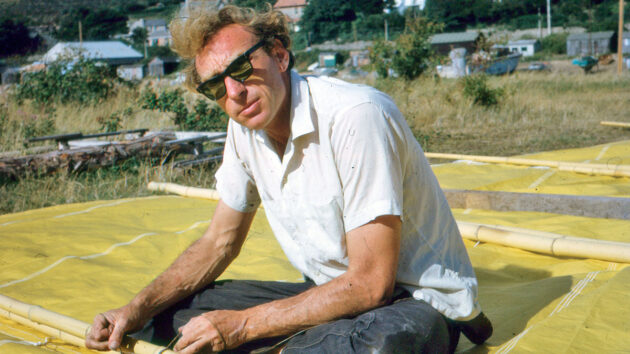

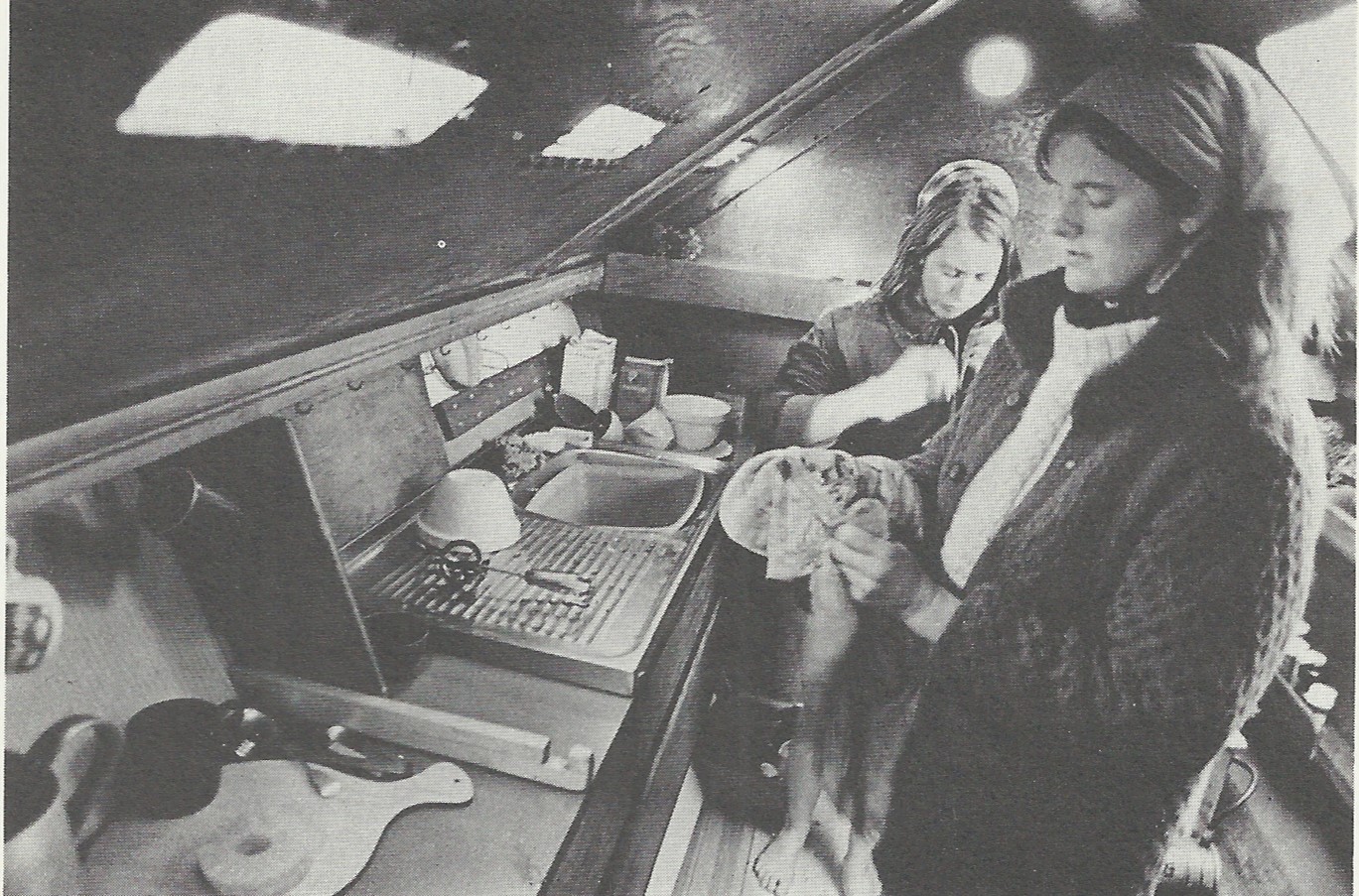

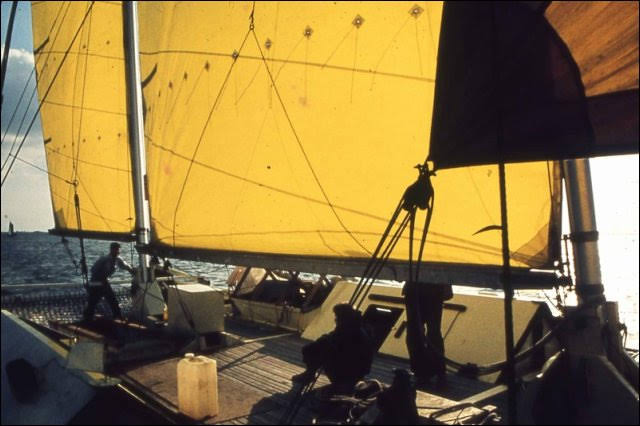

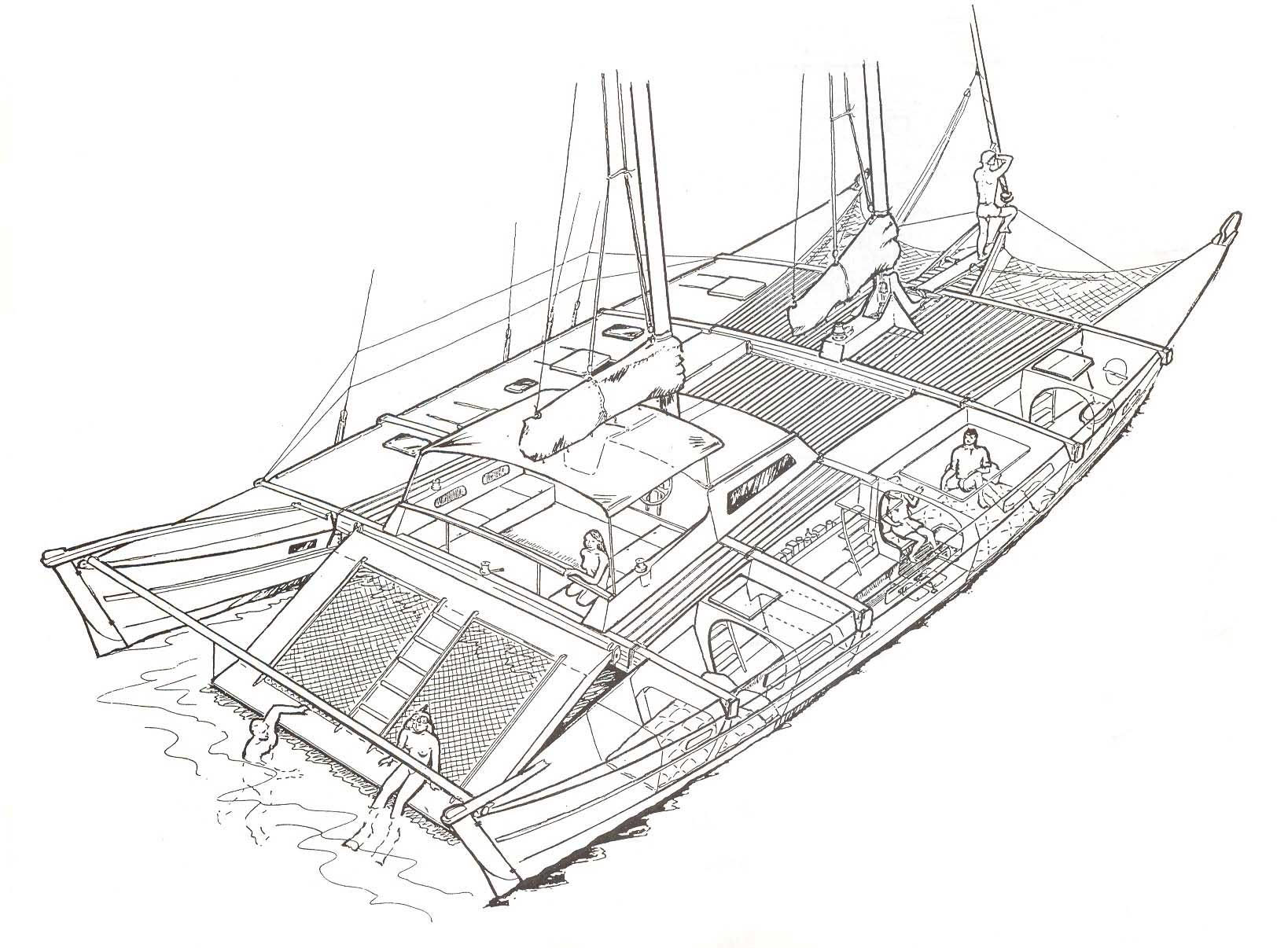

The building of a 52-foot Tehini in 1968 to 1969 however appealed to a lot of people's imagination. The film of this made by Ruth Wharram is now available on You Tube. Establishing a commune like existence of men and women around him was an alternative lifestyle which is now branded as being a hippy one and certainly the image of Wharram catamarans was one of hippy boats.

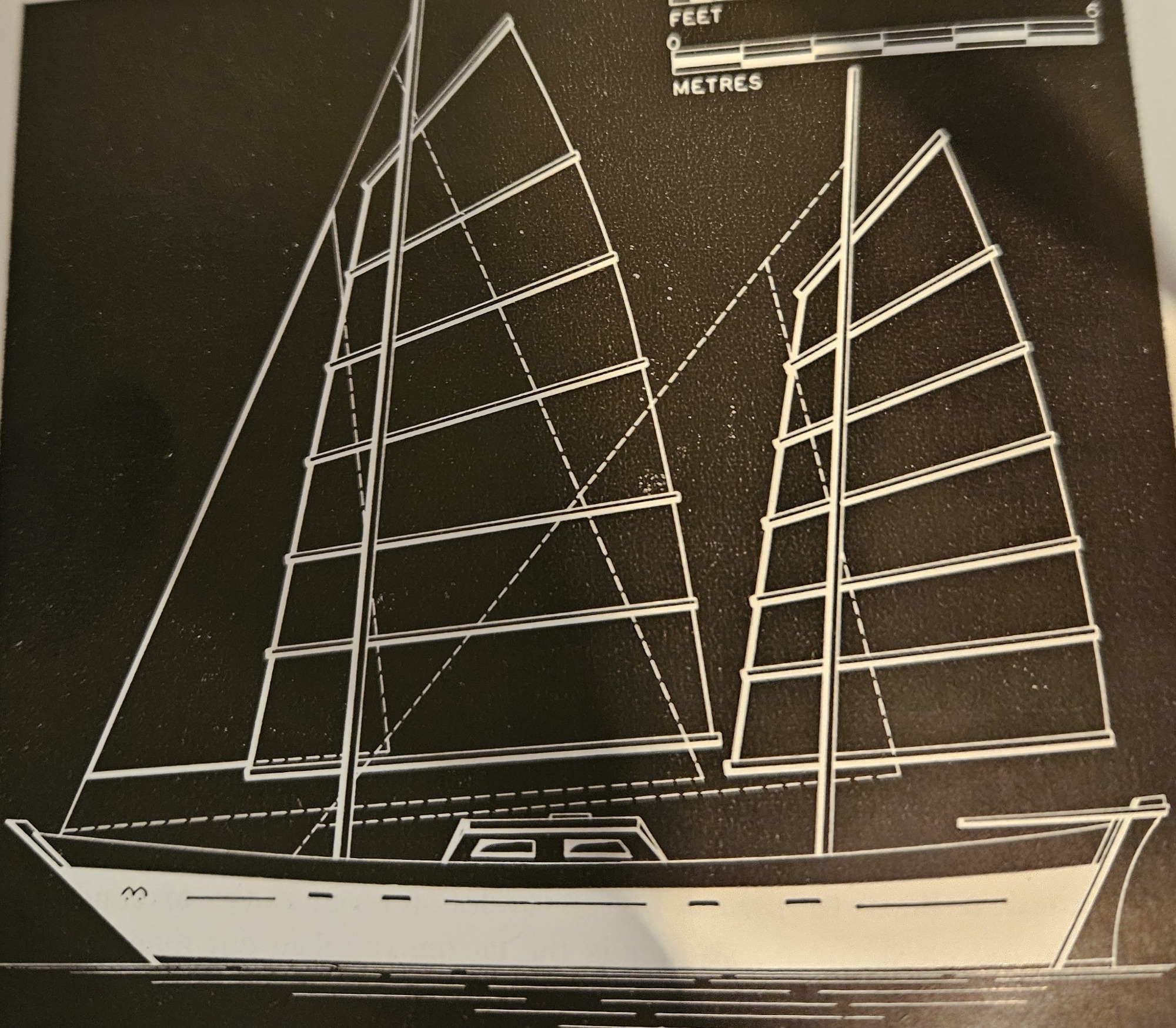

Originally Tehini featured a Chinese junk rig - not a recipe for good performance and after James had written in Yachting Monthly of how brilliant it was, he abandoned it for a more conventional Bermudan schooner and later a cutter/ketch rig.

James wrote a lot about his view that the modern consumer society was doomed in the 70's. His philosophy of escape to live on sea communities fitted into the whole self-sufficiency movement of the 70's and Wharram was still preaching it and the pleasures of multiple relationships, sexual freedom and nudity into the 21st century. He was always seen with an entourage of women and was open about nudity in his books and later littered his design catalogues and study plans with naked women figures.

His personal life was very unconventional as he was married to Ruth, and openly in sexual relationships with at least three other young women who also lived with him and were soon joined on Tehini by young Hanneke Boon who was still a school girl when she first met him.

Between the 70's and 80's the Pahi range was evolved too with hull shapes chosen to resemble genuine Polynesian concepts something they took further in the voyaging canoes they built for the 2008 Lapita voyage which was the antithesis of Heyerdahl's Kon Tiki expedition and proved the viability of double canoes with hulls based on examples of native canoes with traditional Polynesian style sails migrating East to West to Polynesia.

In the 1990's Wharram and his wives (he always lived polygamously although married first to Jutta, then Ruth and lastly after Ruth passed away to Hanneke) sailed around the World in the 63 foot Spirit of Gaia. They attended a Polynesian voyaging rally of canoe replicas in 1995. They were not made as welcome as they would have wished. Manchester's own Polynesian had called his business "Polynesian Catamarans" for many years (until he decided to call his boats "double canoes" rejecting the western term "catamaran") but a white Englishman was not as recognised as the great pioneer as he would have expected even after sailing half way round the World at the invitation of the organisers.

Wharram lived his entire life fighting the "establishment" on behalf of ancient Polynesian peoples and their sailing boat concepts and to suffer exclusion by those same people must have been an awful experience for such an enlightened man. It was a reaction to colonialism that the reawakened sense of their history, cultural and traditional skills were celebrated by the Polynesians and that the intervention of Westerners like Ben Finney and Dr David Lewis in the formation of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and its replica canoe Hōkūleʻa was resented by some of the people rediscovering their navigational skills and their history who wanted the voyages to be carried out by genuine Polynesians and not Westerners. That they did not appreciate James Wharram's contribution to proving that the double canoe concept was seaworthy was ironic given how James had lived his life dedicated to reviving this traditional form of vessel.

There is a lot of written material available now about the sea people of the pacific and their double canoes and navigation revival. None of it credits James Wharram's early voyages with the efforts he made to establish the seaworthiness of double canoes.

Studying the journals of the AYRS, the pages of the UK's Multihull magazines and later the popular yachting press which finally started to appreciate Wharram in the 70's he shines out as a very opinionated character who seemed to be determined to pitch himself against convention at every level in his designs, his personal life and his confrontational approach to the establishment and yachting scene in general..

While the UK yachting community bought the grp catamarans from Bill O'Brian, Prouts and Sailcraft with their comfortable bridge deck cabins, Bermudan rigs, keels and centreboards and the trimarans of Piver, Kelsall and Crowther, Wharram railed against these concepts arguing the superiority of his plywood V shaped hulls, open slatted decks and lack of any protruding boards or keels. When he could not claim superior seaworthiness, he could say his designs were cheap and easy to build and he promised ordinary people the ability to build boats and live a fantasy-like lifestyle as "sea people".

The books "Two Girls, Two Catamarans, in 1969 and "People of The Sea" in 2020 tell the story.

In the late 70's there was a series of capsizes involving trimarans. The success of racing trimarans from designers like Kelsall, Crowther, Newick, Shuttleworth, Walter Greene and Andrew Simpson made them the number one choice for ocean racing. Competitors such as Tabarly, Tom Follet, Walter Greene, Phil Weld, Alain Colas and the amazing Mike Birch were winning ocean races and they all raced double outrigger trimarans. However the prospect of wave induced capsize was emerging as an issue.

The design of multihulls was still experimental. Outrigger buoyancy and the shape of the hulls, and the volume of the hulls were still being developed.

James and Hanneke wrote an article on stability that concentrated on the idea that sail areas should be kept low an idea James had argued consistently as early as 1967 after the CSK catamaran Golden Cockerel capsized in the Solent while racing. They espoused a theory that only double outrigger trimarans were subject to wave induced capsize which was far too simplistic. Like many multihull enthusiasts they assumed that a catamaran's raft like "form stability" could survive breaking seas and slide away. The capsize of Weld's Newick trimaran Gulfstreamer in 1976 plus the loss of the 53 foot Seiko/RTL (ex Three Legs of Mann II) were attributed as had another Newick Val's capsize, the loss of a Kelsall and a Simpson -Wild trimaran in 1977 were all attributed more to big waves than wind.

The problems of roll inertia caused by the heeling of trimarans and low buoyancy outrigger floats certainly produced some wave capsizes but many combinations of wind and waves caused other multihull capsizes too.

James and Hanneke had written that these double outrigger craft instinctively felt unsafe (based upon Wharram's experience with his trimaran in 1966 which had low buoyancy outriggers and little reserve buoyancy at all) and suggested that the craft would heel too much when struck by a wave and that the effect of the main hull and outrigger was that of a narrow catamaran. In his last book James/Hanneke still argued that this was right. However reading the article again now it is clearly mistaken because the centre of buoyancy even in a low buoyancy float trimaran, is the main hull and the righting arm is measured to a point where the outrigger fails to support the weight of the other hulls.

A catamaran righting arm is measured from the centre of the overall beam to the centre of buoyancy in the lee hull. A crucial factor is the righting effect of the windward hull up to a point; after that point a key factor is the submersiibility of the lee outrigger. If the lee outrigger submerges the tri capsizes around the main hull and the wave may also push the windward hull up accentuating a rollover. With full buoyancy floats the vessel will not trip over the lee hull as easily. Research and tank testing has since established that low buoyancy floats and the extra rotational moment can make a trimaran more likely to be capsized by a wave. However this is a problem for all sorts of craft and the use of suitable tactics, running off, towing drogues and lying to a sea anchor are now part of multihull seamanship for trimarans and catamarans. All vessels are in danger in breaking waves and seamanship is necessary. A very fast exciting multihull is not going to be the best at surviving in terrible seas.

The diagnoses of the symptom in James and Hanneke's article was correct in the sense that capsizes were occurring but the reasoning in the article for the cause was a little wide of the mark. It was a lot more complex than they suggested.

Other designers and tank tests have established that there are good reasons why these capsizes occurred. Kelsall and Lock Crowther made their trimarans safer by enlarging their floats and putting in more volume of buoyancy. Both those designers then moved away from trimarans as preferred Ocean Cruisers or racers.

The large extremely buoyant cruising catamarans so popular today have the seakeeping properties of rafts,

However back in 1968 James sold designs like Hina, Tangaroa, Narai and Oro were very simple designs with low rigs, and tiny cabins. Many were built by inexperienced “wana be” sailors, and they did not always have the seamanship skills to sail the boats resulting in some disasters. However, many of the builders were able to achieve long ocean voyages all around the World. From the early 1980s after his life in Ireland with five women in a commune failed and he broke up with all but Ruth and Hanneke, James moved to Cornwall for the last 40 years of his life and designed small day sailing catamarans starting with the Tiki 21. He marketed the idea of holiday escapes and weekend sailing for people who did not reject land-based lives with jobs.

Throughout his life James pitted himself against the mainstream and was critical of luxury catamarans which dominate the multihull market saying they were for western "land" people who wanted a boat that was like their apartments. He was very critical of designs that could capsize easily because they were over canvassed, but the reality was that his designs could capsize too when the owners owners or builders enlarged their rigs from those designed and added centreboards or dagger boards or other keels to improve speed and windward performance.

The Wharram tenets of flexibly connected hulls, low multi masted (most were ketches or schooners) and often gaff rigged or at times junk rigged or using a version of a Polynesian sprit sail (and in his earlier designs using the spritsail itself). The lightweight Tiki 21 and 26 models were both capsized in the hands of crews that did not appreciate that they had limits; this is true of most multihulls that inexperienced sailors or contrarily experienced mono hull sailors fail to detect that they are on their stability limit because they do not heel over. Wharram never changed his opinion that multihulls had to be sold as safe family boats and freedom from capsize was an essential starting point.

He could be quite forthright and was clearly not a man to suffer fools gladly particularly when those fools were his competitors like Arthur Piver, Derek Kelsall, John Shuttleworth, Roger Simpson, Richard Woods and Ian Farrier and many others all of whom he criticised for being "city men" and that he thought put speed over safety from capsize to sell designs.

James dismissed the arguments by Kelsall and Shuttleworth that multihull development was to be found in test tanks and computer programs and preferred to look to principles he derived from study of Polynesian designs and empirical sailing experience for all the answers. Relying upon his own experience and voyages he claimed to know what made multihulls seaworthy because of his sailing - a view which of course did not give credit to the experience and ocean voyaging of other designers particularly Piver, Kelsall, Newick, Crowther and Shuttleworth all of whom had experience of long voyages, and had also done trans-Atlantic's and had other sailing experience that distinguished them as sailors who designed boats.

James always established his credentials based on talking about his Atlantic crossings and implied he had more Ocean experience than others. Perhaps the others chose to be more modest about their seagoing experience because they were also aware that their knowledge and expertise was very much evolving and it is evident particularly in the writing of Kelsall, Shuttleworth and Newick that they were aware that they still had a lot to learn. Pat Patterson for example was famous for his bestselling Heavenly Twins family cruising catamarans, but he had sailed extensively with two circumnavigations and several Atlantic crossings to his credit in his own designs about which he was incredibly modest. Comparing the state of the art in multihull design in the 60's with what is being designed and built now shows that the view that multihull design development had a long way to go in the 70's was quite correct.

But throughout his career James clung to his design principles established in the 50's of V shaped hulls, open slatted decks and canoe sterns with flexible beam connections. That said James’ sales success, the number of boats built to his plans and above all the number of voyages made in his designs are his epitaph. Many people empathised with James' values and his political, philosophical and lifestyle ideas teamed with his devotion to Nature and learning lessons from Stone Age sailors to build boats that owed nothing to modern mainstream yacht design.

He cultivated his role as the great Jim leading his tribe of Sea People to a better place than suffering in consumption driven wage slavery of western society destroying the Planet.

The early journals of the Polynesian Catamaran Association that James had created around his designs and the people that built and sailed them are available online and are an interesting read. They tell the story of how James gathered many aspiring catamaran sailors and builders to his designs. He had a vision of a great body of people sharing their experiences and voyaging and sharing the results.

Sadly it did not quite work as he so inspirationally wrote. Some sailors of his designs lacked skills and experience. Unlike many designers he seems to have encouraged his early builders to be creative with the designs too which produced some odd interpretations of the plans -some more successful that others which caused breakups at worst and ugly aberrations of the designs.

The film about the building of Tehini shows that the craft was rather roughly built with tar all over the hulls and roofing felt and tar used on the decks -not something you would see at Camper & Nicolson! The strange triangular cabin tops made her look very homemade and indicate that she was indeed built to a very tight budget. It is no surprise that the vessel was very short lived launched in 1969 she was deemed too rotten and unsafe to sail by 1985 and in about 1990 she was burned. Wharram's Rongo had been built in 1957 and was effectively a houseboat on a beach ten years later. In 1969 James gave her away to the Sea Scouts who sank her. when they tried to take her to sea. But some builders assembled beautiful craft to his plans and the Spirit of Gaia was built to professional standards in 1984 and sails in Portugal now under Hanneke's command.

It must be said that Wharram's early wooden catamarans suffered extensively from rot due to what was essentially poor design with metal fittings and bolts being breeding points for water ingress and rot. Later designs tried to address this with careful epoxy sealing of all the holes and lashing to avoid the metal bolts and fitting that caused rot.

By no means were they the only plywood multihulls to suffer rot because this type of construction especially back in the 70's before epoxy resin took over, is afflicted with rot when water ingress occurs. But also, the primitive low aspect ratio rigs and lack of keels meant that close winded sailing and powerful windward ability were never really attainable by Wharram catamarans. Strangely James was never a designer who drew his own designs. He would imagine what he wanted and was a boat builder, but he relied upon his associates and later Hanneke to do all the drawing of the plans and Ruth and Hanneke did all the mathematics.

After the collapse of "James Wharram Associates" in Ireland James, Ruth and Hanneke went to Cornwall and rebuilt their lives. By the time he wrote his final book in 2020 he or Hanneke who co-wrote it, was able to see where a lot of the blame lay in James himself and his arrogance and a mistaken belief that taking part in the Round Britain Race courting publicity (in 1966, 70, 74 and 78) would give him the credibility and recognition he obviously wanted.

In fact all these racing adventures just showed up the shortcomings of the Wharram designs, the disastrous trimaran in 1966; Tehini would not go to windward with her junk rig in 1970 and abandoned the race again on the first stage; in 1978, Maggie Oliver one of his closest female companions sailed her with his friend Bob Evans and suffered the structural failure of the main beams and retired from the race. The reason for her retirement was said to be blown out sails; in 78 a grp foam sandwich Tane Nui started to fall apart with major structural problems and the 35 foot Pahi prototype proved so wet and exposed her crew had a terrible time and finished well down the fleet as one would expect for a boat with no keels and just small ineffective dagger boards and a tiny rig.

Other designers were also influential in the home build market like Kelsall Shuttleworth and Wharram's former protégé Richard Woods who had started up in competition (as James saw it). Kelsall was also marketing his own range of self-build designs in GRP foam sandwich. In time James handed over the PCA to others having believed that he had got it back up and running. Unfortunately, this developed into a dispute because James felt he was having his own business stolen by others who took up roles in the PCA and built their own website and business around Wharram catamarans.

The reality was that James' idealistic ideas for the PCA did not work because the whole enterprise centred on the ideas of James Wharram and t the boats were his concepts and designs. After the PCA stagnated a little James took over running the PCA in 1982 editing the Sea People Magazine himself. The association came back to life and in the 90's he and his women stepped back from the PCA.

James had been busy throughout the 1980's and 90's both designing, running his own professional boatbuilding business, building his 63 foot flagship "Spirit of Gaia" and sailing her around the World in stages, while also developing new building methods using epoxy, and the Tiki range of designs which were much more sophisticated than his older design. Eventually James concluded that others in the PCA had started to build their own business about the Sea People community dream and also "improved" the designs creating their own rigidly monocoque versions some with the deck cabins he so loathed and so James felt he was forced to take legal action to protect his business identity and his intellectual property rights to 'Wharram Catamarans'.

This dispute was very nasty and bitter on both sides and it killed off the PCA.

However what has grown up in its place over the past 25 years on the internet is a big community of people sharing stories of their Wharram Catamarans, their experiences building them and sailing them, on several social media and websites. It seems that the spirit of what James intended when he formed the PCA in the 60's is alive and well in a thriving Wharram interest community like nothing else in the multihull world.

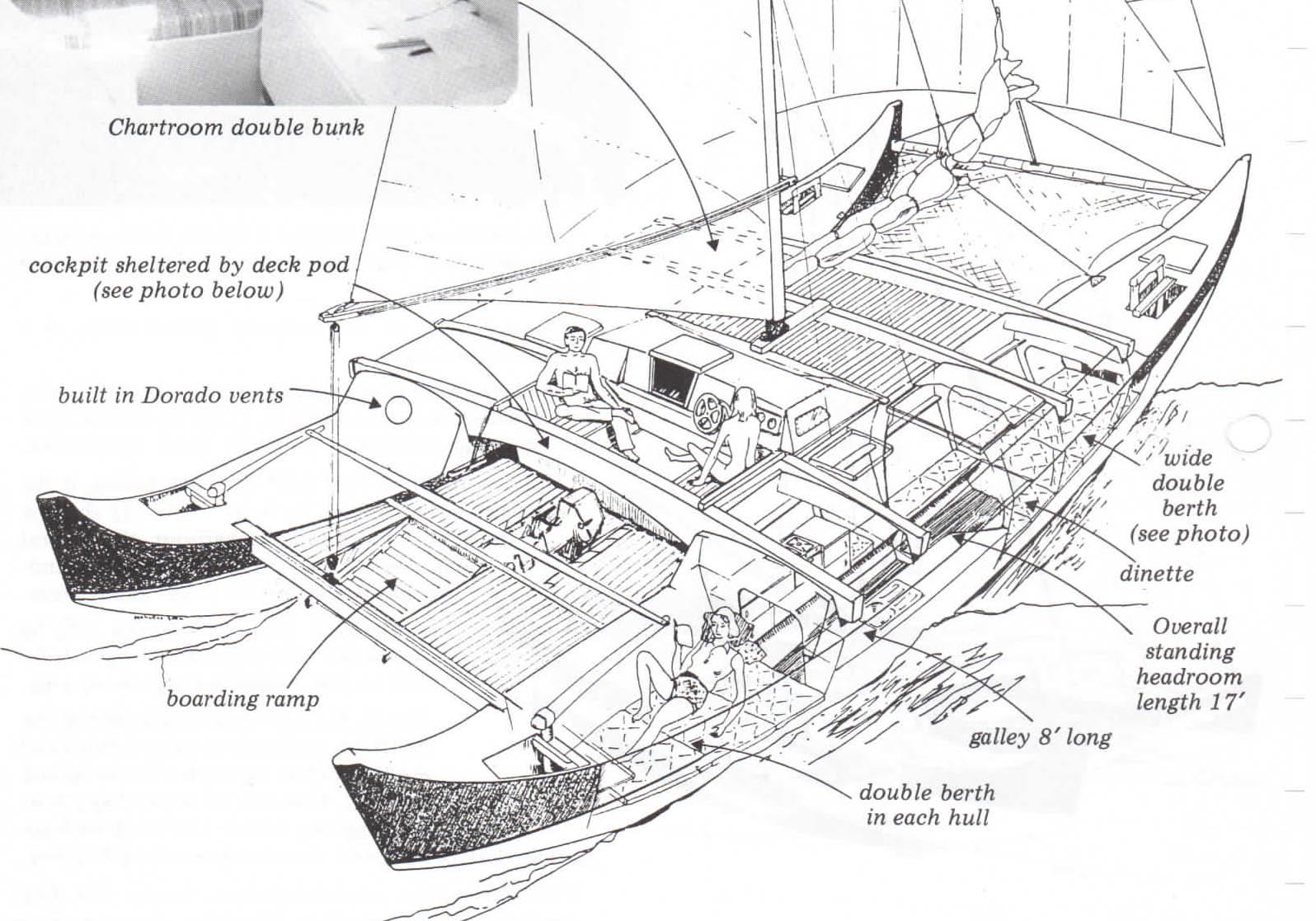

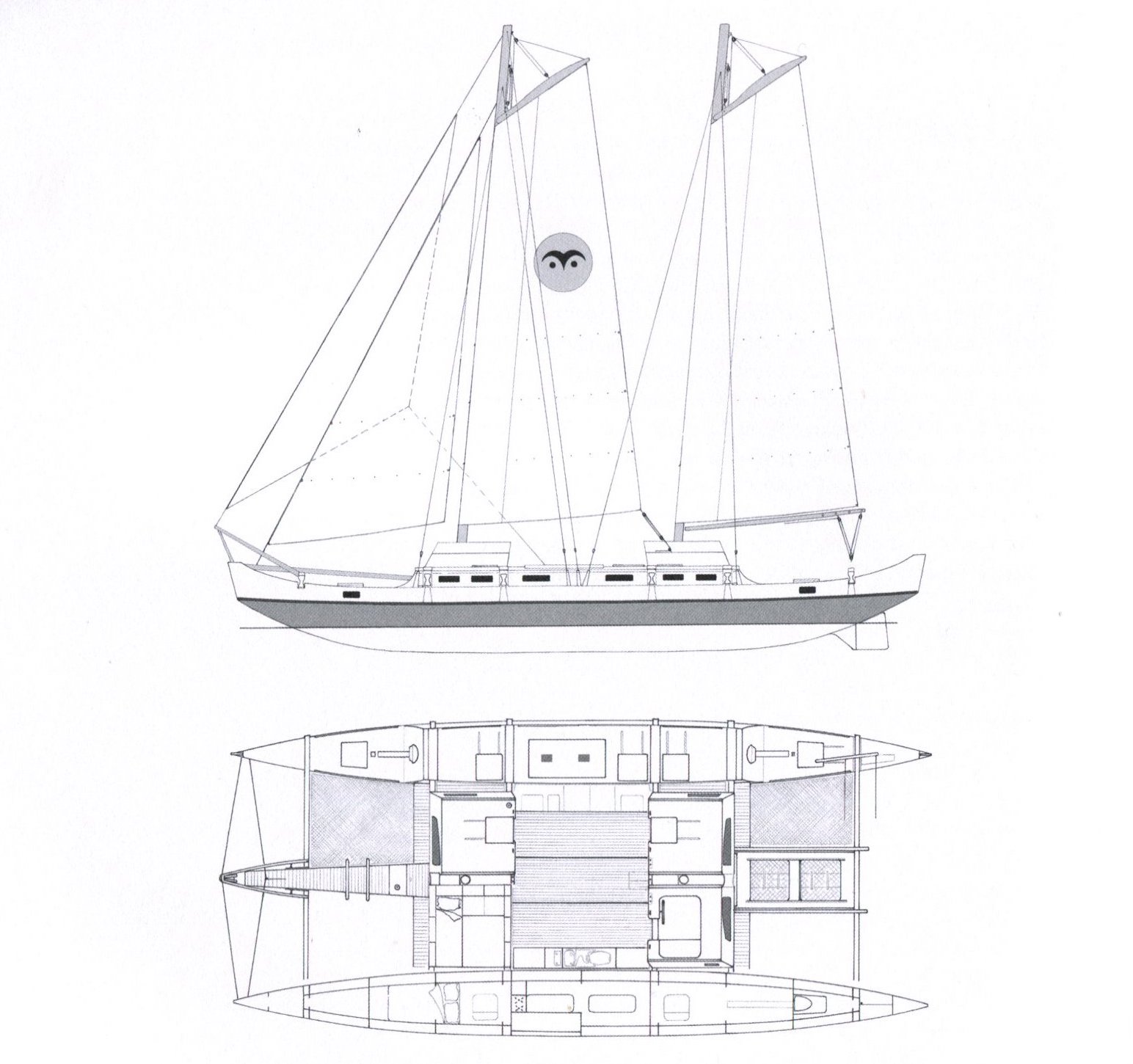

James wrote copious articles and papers with the help of his associates which with his books leaves a great record of his ideas. By the mid 1990's he and Hanneke produced their best designs after the Pahi 63; the home build Tiki 34 and 46 and the Islander professional designs. these featured cockpits and crew cabins on the slatted decks and superior accommodation lay outs that were designed to be comfortable and even had showers and toilets rather than the bucket in a locker approach of past Wharram designs.

Later they developed especially "ethnic" designs like the Wanderer and Mana 24 a kit boat. They developed a new concept of a wing sail that was more effective to windward. Their boats had shallow keels for improved windward ability. The hulls were sharper and faster in shape.

His final book People of the Sea is a fabulously produced gallop through his eventful life which encompassed great self-belief, courage, and the consequences human flaws too.

Sadly, as old age and dementia caught up with him, he was brave enough take his own life which in the context of Assisted Dying coming into UK law in 2025 shows that James was in many things a man well ahead of his peers.

James may not have really invented the modern catamaran, but his story is a heroic one and unique to World multihull development. What he did was brilliantly promote his types of multihulls (he designed catamarans, at least one proa and a trimaran) and his personal design concepts that are unlike any others. Apart from his books and articles I have referred to Hanneke and James published a celebratory photo-book and plan set of Rongo on the 60th anniversary of her 1959 Atlantic voyage. It contains some fascinating photographs and Newspaper articles. It was wonderfully evocative of the age and really brings home the pioneering spirit of the Rongo's adventures.

But above all James personified the spirit of adventure, self-sufficiency, and striving to live the life you desire unfettered by conventions of society.

His individuality made him stand out and he clearly struck a note that many people were attracted to and was a most influential and inspiring character. He probably inspired more dreams than people actually following his path but there were a lot of those too. Hundreds of his designs were built and went ocean voyaging. Others did follow his path and use his designs to become "Sea People" and that is the Wharram legacy.

©Copyright. 2025 Trilogy Sailing Ltd . All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.